From The White City to a New Career

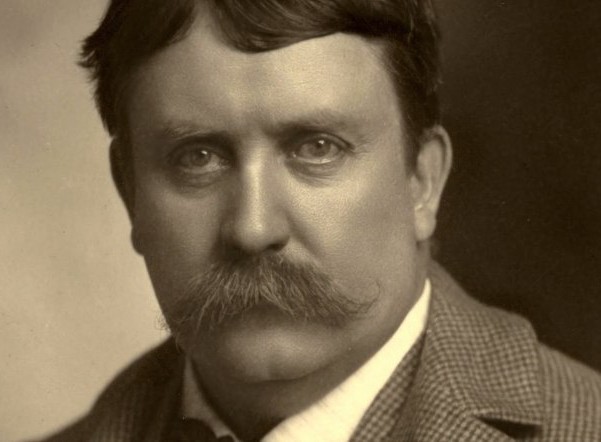

Daniel H. Burnham

By Megan McKinney

When Daniel Burnham completed his colossal 1891-93 undertaking, leading America’s greatest architects in creating a spectacular make-believe city in Chicago, he emerged with a new layer added to his resume—urban planner.

And, as newly elected president of the prestigious American Institute of Architects, he found himself addressing the mediocre design of Washington’s newer government buildings and the city’s deteriorating public spaces.

World’s Columbian Exposition, a planned city

This led him to become, in 1901, “de facto chairman” of the Senate Park Commission. Informally known as the McMillan Plan for its originator, Senator James McMillan of Michigan, the goal was to update and enlarge—but also to refine—the 1791 plan for Washington D.C. by French-American military engineer and architect Pierre-Charles L’Enfant.

The turn of the century National Mall was Victorian and romantic in spirit, characterized by winding sidewalks and casual arrangement of trees. But it was also a hodgepodge of unrelated roads and buildings. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad terminal stood directly on the Mall, with associated sheds and tracks crossing it. In short, “America’s Front Yard” did not communicate a dignity appropriate for the capital of a great world city.

A planning commission was organized, with Burnham as its head. Others were, clockwise from upper right, Charles F. McKim, of New York’s preeminent McKim, Mead & White architectural firm; sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. “Rick” Olmsted was, like his father, a landscape architect.

With the foursome was Charles Moore of Senator McMillan’s office.

Burnham was in and out of Washington throughout early 1901, spending all of March and April “saturating” himself with the city’s atmosphere. This was in preparation for a European journey the little group would make in June and July. Saint-Gaudens, recently diagnosed with cancer, did not join the others.

Camille Pissarro’s interpretation of the turn-of the century Tuileries

Burnham, McKim, Olmsted and Moore sailed for France on the Deutschland, arriving in Paris on June 29. After spending time studying the Tuileries Gardens, Bois de Boulogne and the streets and plazas of the city center, they moved on to Rome, Venice and Budapest. Then it was back to Paris and out to the gardens of Versailles and Fontainebleau. On to England, with special attention to Hyde Park, Hampton Court, Oxford and Eton. The trip back to America on the Deutschland, from July 26 into August, was spent in concentrated work, assimilating all they experienced, with regard to a plan for Washington.

The plan submitted in early 1902 was generally well accepted but would be implemented only over a period of time. A crucial factor, in which Burnham played a dual role, involved the railroad terminal and network of tracks standing on the Mall site. The location, although convenient in the eyes of Alexander J. Cassatt — president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, which controlled the offending rail line—was a major interruption in the grand sweep of the projected plan. Almost coincidentally, Burnham had been engaged as architect for a replacement terminal. And, happily, President Cassatt shared esthetic genes with his sister painter Mary Cassatt.

Pennsylvania Railroad President Alexander Cassatt, painted by his sister Mary Cassatt.

The fortunate outcome is that Cassatt decided that if the government would indeed improve the Mall he would give up the present location and Burnham’s new terminal would be built north of the Capitol.

Daniel Burnham’s handsome Washington Union Station, completed in 1907.

In his new career as city planner, Burnham collaborated on designs for Cleveland Civic Center in 1903 and—at the request of the American government—designed plans for the Philippine cities of Manila and Baguio in1905. He also drew up a plan for San Francisco that year—the timing was astonishingly precise for city that would burn as result of an earthquake the following year; however, the plan was never implemented.

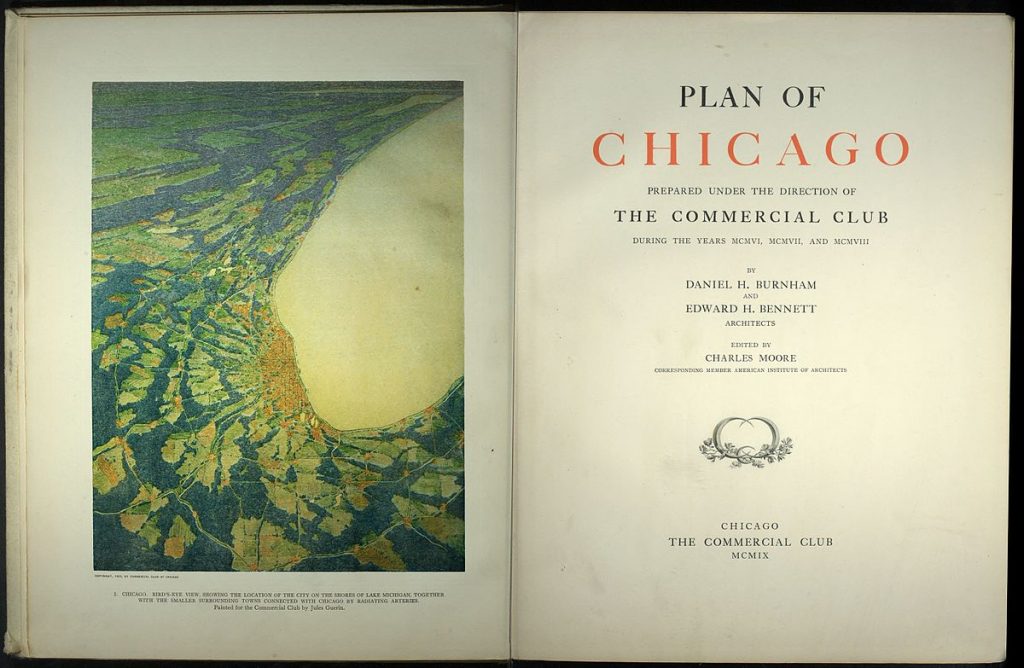

What today’s Chicagoans remember about Burnham is the 1909 Plan of Chicago. Sponsored by The Commercial Club of Chicago, the plan was developed by Burnham and Edward H. Bennett.

Edward Bennett came into Burnham’s life as his “able new planning assistant” during the San Francisco phase. The young English architect and École des Beaux-Arts graduate was, in the words of Burnham biographer Thomas S. Hines, another Daniel Burnham: “a deep and reverend spirit” and “a poet with his feet on the earth.”

The Commercial Club sponsorship was a long time coming and in a round about way. In March 1897, four years after the year of the Fair, Burnham presented a paper detailing his thoughts for the future of the city to the membership of the club, the city’s oldest, most prestigious and financially substantial business organization. A month later, Burnham did the same with the Merchants’ Club, a younger, more progressive—however somewhat less substantial group. Through the following years, the Merchants’ Club showed more interest in the Plan, but it wasn’t until after the 1906 merger of the two clubs under the Commercial Club umbrella that there was a substantial forward move.

The Plan of Chicago, as published by the newly enlarged Commercial Club, featured renderings such as that above to convey various possibilities for the rapidly expanding city. Burnham’s continued recommendations included new and widened streets, enlargement of the city’s park system and civic buildings, new rail and harbor facilities, and enrichment of the lakeshore.

Charles H. Wacker, Vice Chairman of the General Committee of the Commercial Club, was appointed Chairman of the Chicago Plan Commission by Chicago Mayor Fred A. Busse in 1909. Meanwhile Burnham and Bennett worked together, with Bennett creating the myriad drawings and layouts and Burnham raising visibility and money. As with Burnham’s plans for other cities, only portions of the Plan have been realized; however, it made an impact on the new area of urban planning. And Plan Commissioner Wacker made certain the rising generation was aware of it with his persuasive Junior High School textbook.

Tragically, Daniel Burnham died suddenly while on a 1912 vacation in Germany; his successor firm, Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, carried on for decades. Among its designs is one that continues to be one of Chicago’s great signature constructions, the shimmering Wrigley Building of 1922.

This segment concludes Classic Chicago Publisher Megan McKinney’s four-part series on Architect Daniel Burnham.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl