By Francesco Bianchini

There was no more thrilling moment than those evenings when my mother and father went out to dinner, or announced they’d not be coming home. A breeze of mild anarchy blew through the house. Although ephemeral, these events marked a break in custom. For starters, there was no need for a cook for us children, or for our elderly aunts who were already on a diet of semolina, cottage cheese, strained apples – and who, depending on the mood and the season, preferred to dine in their separate rooms.

Our gang of five (two more yet to come!) with me, the ringleader, seated on my throne.

In mom and dad’s absence Rodolfo, who always crept into spaces left unattended by my parents’ authority in a way like those seemingly harmless cracks that bring down the most solid of buildings, enjoyed the infamous role of kapo to whom nothing and no-one escaped. We didn’t fear him at all because, in reality, his only blunt weapon was denunciation, which had little grip on my parents. So we ignored him trotting around the house, busy in the kitchen, checking on our movements, all the while dedicating himself to some mission that would allow him to shine when mom and dad returned. During the few hours of my mother’s absence, for instance he’d surprise her with the efficiency of his proxy. Sometimes we caught him crouching in front of the washing machine, pushing the knob forward to speed the cycle, so that in one evening he could do three loads of laundry and hang out the clothes in soapy rigor mortis.

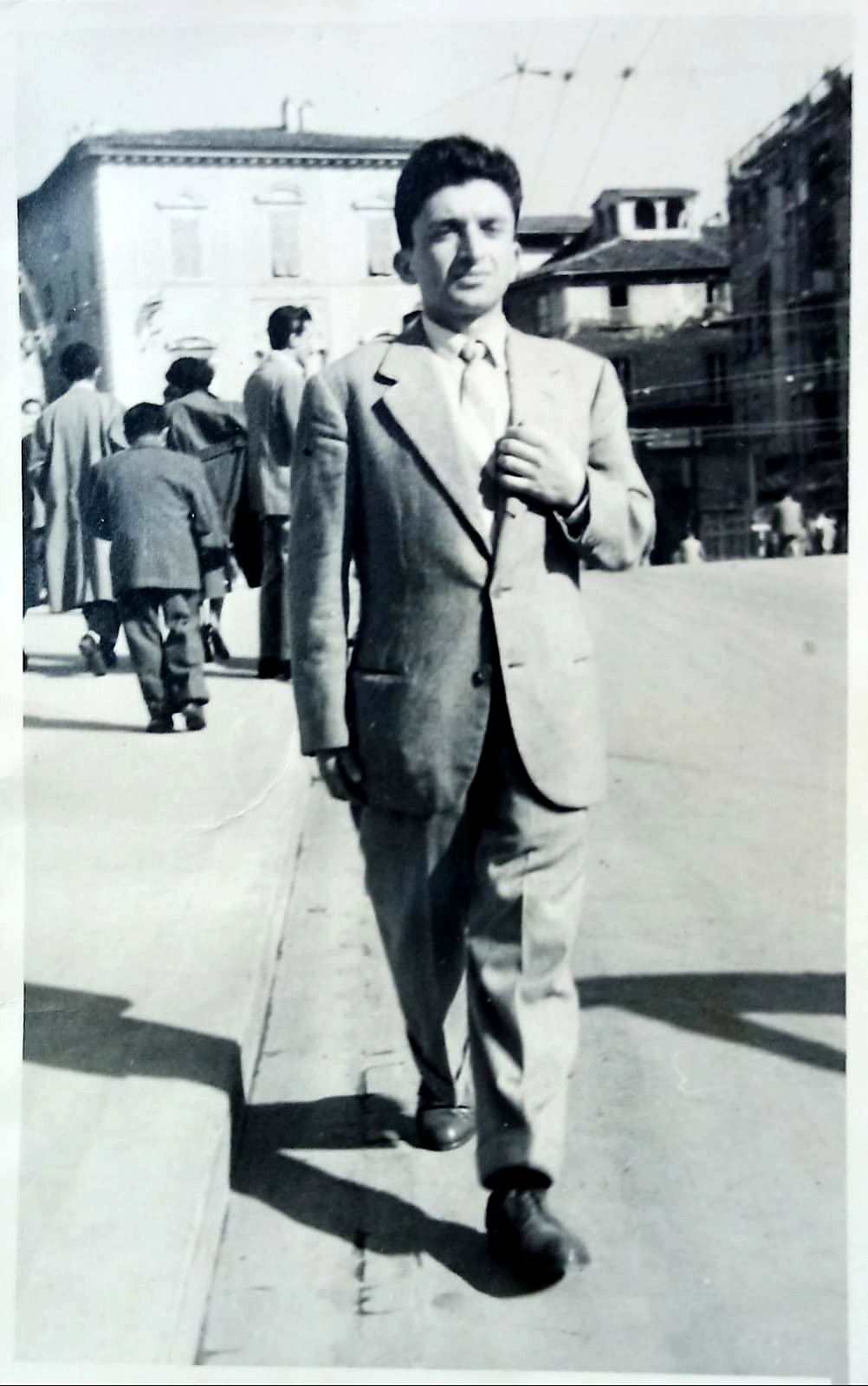

Rodolfo, ever the flashy dresser, goes to town, circa 1950

We valued the intoxicating idea of unsupervised freedom over its practical applications. I’d spend those evenings locked in my father’s study, playing pranks on the telephone, manufacturing plots of my own imagination while hidden in some out-of-the-way closet, or leading expeditions to the attics to rummage through closets that my mother kept locked, to disguise ourselves in whatever we could find.

Family kitchen

Dinner on those evenings was essentially of two kinds: either a prosaic replica of breakfast with cafe latte, bread, butter, and jam; or more often – and by popular demand – bruschetta and frankfurters sautéed in a pan. Rodolfo, to whom any concept of moderation was foreign, would prepare a plate overflowing with bruschetta dipped in our own family’s olive oil, some slices more burnt than others, which was a natural consequence of his comings and goings, from which he scraped the blackened parts with a knife. The aroma of that toasted country bread soaked in oil with its beautiful golden color, made a memorable display on the long cypress table in the dining room, insinuating itself into my evening preoccupations. When called to the table, I resorted to expedients to prolong my wait for that pleasure: hiding in a dark cold room, counting to one hundred, imagining adverse weather, impending dangers. Rodolfo would call me from a distance, so irritated with impatience that his voice rose to the level of a shrill falsetto. Only then would I rush to the warm and fragrant dining room, bolting the door behind me against the brigands, werewolves, and spectres of the woods.

Bruschetta in its golden olive oil

The frankfurters, actually called würstel by us or ‘gustel’ according to Rodolfo’s phonetic transcription appeared, sometimes accompanied by sliced meats and other delicacies; a smorgasbord unthinkable in the presence of mom and dad, and which conjured for Rodolfo a gentrified and comforting idea of abundance – the degree of under-doneness directly proportional to his level of sobriety.

Our favorite ‘gustel’ from the pan

Of course, I’m extolling junk food to devotees of exemplary flavors and handed-down culinary know-how – but let anyone cast the first stone who, as a young child of the post-war period, and therefore of the advent of food on an industrial scale, did not have a personal Eldorado composed of similar treats! My ancient great aunt Gabriella – who would have happily munched on bruschetta if she’d had teeth – scolded in an aparté that she could not understand how we children were crazy for such stuff.