By Francesco Bianchini

No man is an island, entire of his self; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. All the more reason, after these months of confinement, to mentally travel to the bridges that humanity has thrown over chasms to unite what nature divides.

During an epic wander in Provence with my mother and sister a quarter of a century ago, we purchased the ingredients to make pan bagnat at the market in Avignon. Think of it as a Provençal variation on Italian panzanella or Cretan dakos – a salad niçoise with tuna, anchovies, hard-boiled eggs, tomatoes, olives – all stuffed into a hollow of bread, moist and dripping. The sandwich is wet with olive oil and the juices sweating from the filling. Getting the right bread is the key to a successful pan bagnat. Be warned! There is a fine line between ‘wet’ and disintegrated: the bread must be sturdy enough to withstand the oil and juicy fillings.

Around noon we were traipsing through the pine forests that overlook the Roman aqueduct that spans the river Gard, seeking the perfect spot for our picnic – sheltered from the mid-June sun but close enough to the river for a swim before lunch. At that time, the riverbanks passing the Pont du Gard were freely accessible, even to swimmers who profited from the coolness of the clear, shallow waters and from the dazzling reflection of the triple order of arches. Mother, Sabina and I ate our sandwiches in the shade of the pines, deafened by the din of cicadas – to be sure, those Provençal ones that don’t produce symphonies by halves.

The Roman aqueduct at Pont du Gard

The Brooklyn Bridge opened to traffic on May 24, 1883. I traveled to New York 119 years later, intrigued by the tradition of certain elderly friends to celebrate the birthday of one of them on the bridge. They staged it annually on the pedestrian lane, calling their gathering the ‘bridge birthday’ that every May 24 brought the group together – former editors, poets, novelists, playwrights. In my childhood in Italy, the bridge was featured on the wrapper of Brooklyn brand chewing gum, another example of an American counterculture completely out of place on the smelly shelves of old grocery stores in an Umbrian village. The gum was strawberry or mint flavored with which we competed to see who could blow the biggest bubbles.

For the bridge birthday I helped prepare deviled eggs; finger sandwiches of tuna, ham and cheese; grilled chicken livers wrapped in bacon, each stuffed with a Chinese water chestnut. Other guests brought bagels with cream cheese and lox; chicken wings with barbecue sauce; chips and crackers to scoop through the American party treat: ‘California Dip’, packaged onion soup mix blended with sour cream. And of course there were brownies from Bloomingdales and plenty of bottles of champagne and cans of soda: too much to eat and drink for a small group of survivors of the Beat generation, but the idea always was to stop passers-by and share snacks and drinks with them. A celebration of friendship, fellowship, and of their love for the city to which each had given everything and from which they’d received so much.

The party bridge

A childhood friend invited me on a glorious June evening to dine – on the grass, she said – next to a Roman bridge in the countryside on the Via Flaminia. Her guests and I were led up a hill between two fields of wheat and then down the old track that crosses the bridge. What a surprise it was to see, in the middle of a freshly mown lawn, surrounded by a curtain of oaks, a richly set table under a white canopy! And what a double surprise to look up from the banquet and see the ancient bridge spanning the bed of a drained stream, an air so martial with its massive stone blocks softened by clumps of pellitory and ferns, yet still serving its purpose. If I have previously spoken of informal picnics, for this affair the term seems reductive. I should rather refer to a dîner champêtre in the manner of Watteau or Renoir. When it began to get dark, pixies lit small candles placed in the cracks of the bridge, the elegant candelabras lined up on the table, torches all around. The aroma of laurel that seasoned some dishes, including a magnificent John Dory cooked with lentils, spread through the clearing. As the ambiance grew, a hush fell over the table; nothing memorable was said. There we sat, perceiving those muted sounds usually inaudible to insensitive human ears: the beating of moths’ wings, the whirring flight of fireflies, tiny leaves fluttering in the breeze which wafted through the foliage clinging to the stones of the bridge.

The Roman bridge near Carsulae, Umbria

Almost every day in Istanbul I found myself crossing the Golden Horn on the Galata Bridge, commuting between the university where I taught for a few weeks, and Beyoğlu which I was then calling home. The incessant traffic – pedestrians, car, trucks, and trams – gives the structure a jolting movement, as if the bridge itself stretches and retracts between the two shorelines, between two worlds facing each other. On one side, the world of fashionable stores, trendy cafes, art galleries, of boys and girls holding hands; on the opposite shore, the other world of segregated sexes, veiled figures, and piles of poor, unassuming merchandise cluttering the sidewalks. In a nearby hole-in-the-wall in Karaköy, I’d buy one of the famous balik ekmek – a grilled mackerel, green pepper, tomato, lettuce, and onion sandwich – to eat while strolling along, careful not to trip on the fishing rods and lines strung across the sidewalks of the bridge.

My photo of fishermen on the Golden Horn

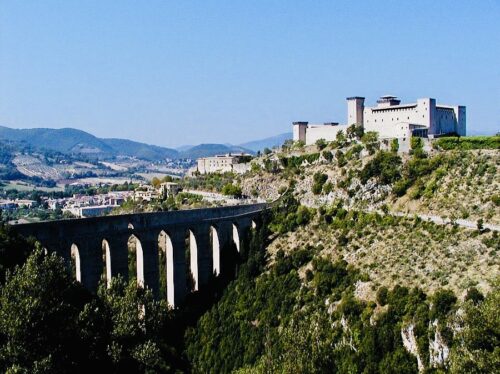

Anything bold involves risks, and a bridge – fragile by its nature – sometimes links the sheer cliffs of an abyss. The view of the Ponte delle Torri in Spoleto, and of the gloomy fortress that rises above it, could be the backdrop for one of Stendhal’s seventeenth century Italian Chronicles – and Stendhalian indeed is a family anecdote, circa 1860, about my great-great-grandmother Caterina. She was returning to the fort, where her father was installed as Papal governor of the city, when the horse of her carriage bolted in mid-span. The situation was desperate, with the vehicle teetering on the verge of the roadbed, and the panicked coachman unable to regain control. But brave Caterina snatched the reins, maneuvering the contraption safely to the end of the bridge. She set an example: not infrequently, women in my family demonstrate their ability to take charge. During World War II, my grandmother Margherita, under the flimsy pretext of ferrying some prelate or other to Rome or Perugia, obtained a pass allowing her to travel. On the Via Flaminia, deserted by other motorists in those days of war rationing and fear of bombing, Margherita sometimes had to change a flat tire while the monsignor or bishop hitched up his skirts and sat on a stone waiting for the trip to resume.

The bridge of Spoleto, with the fortress and governor’s residence looming above