By Megan McKinney

Architect Andrew Rebori’s North Side Chicago designs ranged from the innovative Frank Fisher Studio Houses, above, commissioned by a Marshall Field executive as an investment, to the traditional Racquet Club of Chicago and very proper apartment buildings at 2430 N. Lakeview Ave. and 1325 Astor St.

2430 N. Lakeview Ave.

The above are opposite extremes, with many captivatingly quirky or delightfully traditional variations and surprises in between.

The Chicago Riding Club during construction in 1922.

Think of the eccentric former CBS Building at 630 N. McClurg Court. Andrew Rebori designed it as the Chicago Riding Club, with partners in 1922; after that, it became a skating rink, then, in 1954, CBS realized this rambling, lofty space in a central location was a rare find for the sprawling television studios the station would need.

One of the studios continues to hold a spot in American history as the site of the first televised presidential debate, which many believe gave John F. Kennedy the presidency because of his visual edge over Richard M. Nixon that night.

630 N. McClurg Court before its 2009 demolition.

The building was an anachronism by the time the WBBM-TV studios moved to the Loop in 2008. It was demolished a year later.

The Elizabeth Arden building at 70 E. Walton Place, with its eccentrically climbing duplexes standing in the midst of ever-changing commercial properties, is a 1926 Rebori creation now entering its tenth decade.

Rebori didn’t often venture out of the city; however, Bluff’s Edge, his 1923 Lake Forest house for Wayne Chatfield-Taylor, was a notable example, as were two designs associated with Rebori’s uncle-in-law Colonel Robert R. McCormick: the First Division Museum at Cantigny in Wheaton and McCormick’s burial memorial, also at Cantigny.

1209 N. State Parkway.

The building for which Rebori is best known is the aforementioned 1937 Fisher Studio Houses at 1209 N. State Parkway; a moderne apartment block, recognized for its then highly advanced curved walls, spiraling staircases and glass block windows. Muralist and craftsman Edgar Miller was brought in by Rebori for the building’s distinctive detailing. Behind the curved white brick façade, a dozen duplex apartments look over a narrow courtyard; however, the developer, Frank J. Fisher, lived in a somewhat larger three-story owner’s apartment at the building’s rear.

Examples of the signature curved stairways of the Frank J. Fisher Studio Houses.

Another Andrew Rebori design, popularly known as the Florsheim Mansion, is located a block or so up North State Parkway at 1328. Completed in 1938, it shares with the Fisher Studios such features as curving stairways and glass brick walls.

1328 N. State Parkway.

In 1946, another Chicago architectural superstar stepped in to the development of 1328 N. State Parkway with Lillian Florsheim’s purchase of the property. Bertrand Goldberg, who was married to the shoe heiress’ daughter Nancy, transformed what had been a multi-unit structure into a single family house for his artist mother-in-law. As with almost everything Goldberg touched, the reconfiguring of 1328 N. State Parkway received massive publicity when he connected the main building with a coach house behind it by constructing a long, narrow kitchen at the second-story level, which he suspended over a courtyard below.

1325 Astor St.

A Rebori design, a decade earlier but light-years away from the two above, is the superbly elegant and traditional 1325 Astor St. The discreet address on graceful Astor has the unusual inland advantage of crisp, unobstructed lake views in apartments above the sixth floor.

The exquisite 2430 N. Lakeview Ave. is another traditional Andrew Rebori design and an Establishment favorite. Through the decades, the building’s two-story cooperatives, which feel like spacious single-family houses, have been home to more than a few distinguished Chicago dynasties.

2430 N. Lakeview Ave.

The 5,600-square-foot duplexes are two to a floor, each with an expansive living room, formal dining room, library and service rooms on the lower level. An ample supply of bedrooms, a private sitting room and multiple dressing room/closets stretch across the second floor above.

Although it was 1927 when Rebori designed 2430, he had begun installing the curved staircase for which he would later be known.

The signature Rebori stairway in an early, more sweeping version, connects the lower formal level of a 2430 duplex with the upper family floor.

A New Yorker, Rebori studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, École des Beaux-Arts and American Academy in Rome but received his architectural degree in 1909, at the Armour Institute of Technology in Chicago, where he had become a professor. While in Boston, he met his future wife, Nannie Prendergast of Wheaton, who had been raised on a farm adjoining that of her uncle Robert R. McCormick. They were married in 1913 and eventually became the parents of two.

Andrew N. Rebori, with son Andrew Prendergast Reboriand Andrew’s wife, Barbara, with their two children, Nina and Susan Lee.

After being mentored by Louis Sullivan, Rebori worked in the office of architect Jarvis Hunt until 1922, when he founded his own firm, Rebori, Wentworth, Dewey and McCormick, with three members of the Chicago Establishment, John Wentworth, Albert J. Dewey Jr. and the dashing Leander J. McCormick.

Like Rebori, all were representatives of Chicago’s Twilight Generation, men and women born between 1885 and the end of the century. They had known a world of privilege “before the lamps went out” in 1914 and would experience the texture of “the years between the wars.” Members of their generation would be touched by the drama and tragedy of both World Wars, the Great Depression and Prohibition; they had experienced life surrounded by remarkable design and high style and were marked by a world that quickly slipped away.

The firm dissolved in 1932, when Andrew began working as a single practitioner.

Although Rebori was author of some of the Gold Coast’s most eccentrically modern structures, he had disdain for most modern style buildings, referring to them as “steel and glass upside-down cakes.”

Among the most charming apartments in the city are those at 40 and 50 W. Schiller, which Rebori and his then partners designed in the early 1920s for—according to legend—Racquet Club members who were content with their Lake Forest estates, but who also wished for stylish in-town pied-à-terre’s with convenient access to the club, which is located cater-corner across North Dearborn Parkway.

Inside the courtyard looking out to Schiller Street from between numbers 40 and 50.

Inside the courtyard looking out to Schiller Street from between numbers 40 and 50.

Each apartment in the complex is unique; however, they share such consistent Rebori touches as upstairs-downstairs levels and meandering stairways connecting them.

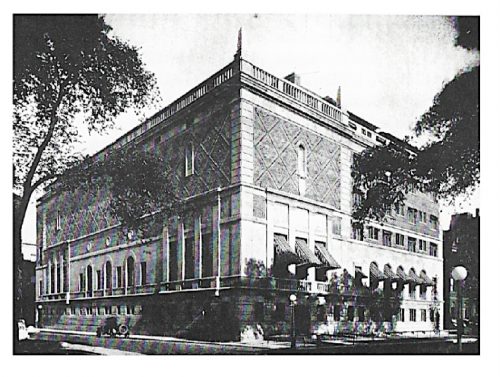

Finally, there is the Racquet Club, designed by Rebori, Wentworth, Dewey and McCormick, and built on a piece of land acquired by partner Albert Dewey in September 1922. Rebori’s original 1923 renderings for the club design were in Queen Anne style; however, when additional land was acquired adjacent to the original Dewey property, Andrew redesigned the building “in the style of the Palace of the Doges in Venice.” Then, when practicalities of court measurements kicked in, Rebori and Leander McCormick traveled to Manhasset, Long Island, to confer with Harry Payne Whitney and take precise measurements of a court of his.

The Racquet Club under construction in 1923.

The Architectural Record, September, 1924

The newly completed Racquet Club of Chicago in 1924.

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl