BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

A flight of fancy or a Cubist portrait of his wife? Picasso’s untitled monumental sculpture in Daley Plaza has been a hot topic of conversation for the last 50 years.

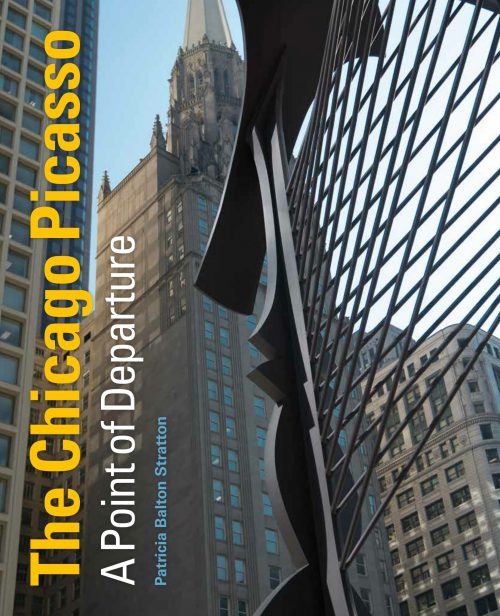

The artist was 85 years old when he completed and donated the model for the 50-foot-high sculpture to our city, accepting no payment. Author and über-volunteer Patricia Stratton tells its story in The Chicago Picasso: A Point of Departure, to be published April 1.

Here’s how civic leader John McCarter, retired president and CEO of the Field Museum, introduces the book:

Chicago is an outdoor art gallery—the Polish heroes along Solidarity, Lincoln seated between the Gettysburg address and the 13th [Amendment],

Shakespeare in his garden, the Oldenburg [baseball bat] on West Madison, Linneaus at the University of Chicago, Lorado Taft’s [Fountain of] Time at the end of the Midway, the equestrian statues of Civil War [generals], the [agora] of 106 iron sculptures in Grant Park.

Often, we deal in results but lose the stories of how all this happened. Patricia Stratton has brilliantly told the story of the Picasso—the artist, the architects, the civic ambition, the negotiations, the design and fabrication, the ownership, the controversy—all the elements that lie behind this most famous of all Chicago [sculptures], and its transformation from drawing and maquette to a monument in 162 tons of [COR-TEN] steel.

Gaze at her for a long time and see what you can see—Sylvette, Jacqueline, Afghan dog[,] or bird[,] or creature of your own imagination.

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the arrival in Chicago of Picasso’s statue to the Daley Plaza, Stratton has updated her thesis, filled with interviews with the principals (architects, engineers, politicians, and steel workers), by traveling to international Picasso museums and meeting with photographer Lucien Clergue, his good friend.

In addition, she spent many hours with SOM architect Fred Lo, who did the original drawings for the maquette in secret at the Art Institute, following the translation of 41 inches into 50 feet and 162 tons.

“I guess I have become hooked on his genius and certainty that he was the greatest artist of the 20th century,” Stratton said recently about her over-fifty- year passion for Picasso. Recognized for her work with nonprofit organizations, Stratton managed volunteers for the Field Museum, raised funds for the Northwestern Hospital Foundation and the Daniel Murphy Scholarship Foundation, and has served on nonprofit boards across the country.

Her enthusiasm for the artist and this city’s most famous sculpture was clear—and catching—in our recent conversation.

Set the stage for Chicago’s acquisition of the Picasso sculpture.

The advent of the Chicago Picasso was a game changer for public sculpture in Chicago. Actually, it was a breakthrough for large sculpture across the country. The international style of architecture developed by Mies van der Rohe was more geometric with clean lines—these tall and somewhat severe buildings rose out of large plazas across the country. These plazas demanded a significant sculpture to humanize the space for the pedestrians passing by and through them.

Mayor Richard J. Daley undertook the renovation of the Loop, and the Civic Center was named for him after his death. It was the first building constructed in this new style with room for a large outdoor piece. It was decided that it would be too difficult and expensive to install a large bronze sculpture, although a Henry Moore piece was considered very early in search for an artist.

SOM’s Bill Hartmann made the final decision that the material would match the building. It was a very brave move to select the new weathering steel, trademarked COR-TEN by US steel for the 648-foot-tall building that covered only one-third of the square footage of that city block. The curvilinear lines of the Picasso sculpture were in sharp contrast to the linear building, and Picasso approved the new steel material.

The Daley Center and the Chicago Picasso paved the way for other new buildings and plazas in the Loop. Next was Mies’s Federal Center, which has Calder’s Flamenco, and Chase Tower with Chagall’s Four Seasons. Soon came the Miró at the Brunswick Building and the Dubuffet at the James Thompson State of Illinois Building.

Why did Picasso choose Chicago as the recipient of his sculpture?

Picasso long wanted to make a monumental sculpture. He accepted a commission in 1928 from the city of Paris for a memorial to his close friend Guillaume Apollinaire, but the project didn’t work out. His design was not accepted, and he never accepted another commission because he felt that would restrict his freedom of expression.

He refused a commission for the sculpture in Chicago but was still interested in creating a large sculpture. He said that he would consider working on a design, but he did not want any restraints and was slow to produce the design that would eventually be accepted by the Chicago architects.

He would not accept any payment, maybe because that would make it appear that he was being paid for a commission. Skidmore architect Bill Hartmann never gave up on convincing Picasso to fulfill his dreams of monumentality in Chicago.

Chicago’s offer came when Picasso was nearly 85, and he may have recognized that this project would be his last, and maybe best, chance for creating a monumental sculpture during his lifetime. He gave the Art Institute the model for the sculpture and the people of Chicago the rights to enlarge it.

Did Picasso visit Chicago to see his completed sculpture?

He never did. Chicago was 4,000 miles away from Mougins in the South of France where he spent his final years.

Picasso was born in Málaga, Spain, and lived in Barcelona and Madrid in his early years. Then he moved to Paris, center of the art world at the time in the first half of the 20th century.

Decades later he moved to the Riviera. He made one trip to London to receive awards and to Holland with a fellow artist, but otherwise he never left the continent.

I have read that there was controversy when the Picasso sculpture was announced. What happened?

When it was announced that Chicago had selected Picasso as the Court House Plaza artist, there were many complaints and questions regarding Picasso having joined the Communist Party in 1944.

He had produced the now famous “dove of peace” motif for an international Congress of Intellectuals for Peace in Paris in 1948. That same year he traveled to Cracow and Auschwitz and attended a second peace conference in England. He received the Lenin Peace Prize in 1950.

Picasso’s interest in communism and politics had been ignited by his deep-felt concern for Spain under the dictatorship of Franco during the Spanish Civil War. But he lost interest in politics and even turned down the French Legion of Honor in 1967.

Mayor Daley told his critics: “We handle politics ourselves. Picasso is the best artist in the world, and that is what we care about.” The issue was over, and the Mayor approved the choice of the artist.

How was the sculpture funded?

Although there were local, state, and federal funds available at that time for art and architecture programs, the Picasso is the only sculpture that was built with no public or corporate money. The construction costs were covered by three philanthropic foundations: The Chauncey and Marion Deering McCormick Foundation, the Field Foundation, and the Woods Charitable Trust.

What most appeals to you about Picasso’s work?

What is so extraordinary about Picasso are his breakthroughs in looking at art from new perspectives and simultaneously from more than one direction. He produced prolifically in so many media: drawing, pencil and ink, chalk, painting, lithography, etching, sculpture, ceramics, and a brief dabble in photography.

In each media he made new discoveries and found answers to ever-changing problems in the world of art. In 2013, the Art Institute presented Picasso and Chicago: 100 Years, 100 Works, which showed not only the maquette but also other works in the museum’s own collection and those of private local donors.

You have been an art enthusiast for many years. How did your interest develop?

After getting my BS in Marketing at Northwestern, I decided to broaden my education and study art history. I was lucky to travel across Europe and visit many museums. While living in the Quad Cities, I was a docent at the Davenport Art Museum, now called the Figge Museum. In Milwaukee, I was a docent at their art museum.

When I moved to Chicago, I headed up the Art in the Schools Project for the Junior League of Chicago, which became associated with the Chicago Public School Art Society, affiliated with the Art Institute. We took the basic principles of art—line, color, form, media, subject, and artist—to classrooms at a time when schools had the arts cut out of their budgets.

I taught at a wonderful Hispanic school, and naturally I chose Picasso as my subject. When I showed slides of Picasso’s sculptures, one of my fifth grade students was overjoyed and said, “That’s what my father does—he welds metal and pipes. He is a plumber.” He was so proud, and I was thrilled to have touched his world.

Stratton now lives in Naples, Florida, during the winter, where she balances several volunteer projects with her writing. She will return to Chicago in April for multiple book signing events.

***

To learn more about The Chicago Picasso: A Point of Departure, visit chicagopicasso.com. Books may be purchased online through major sellers or her publisher (ampersandworks.com).