Perusing the stacks inside the architecture library at the University of Virginia in 1985, Greg Koester came upon Domestic Architecture of Harrie T. Lindeberg, a monograph published in 1940. Though it had not been checked out in decades, Koester relished turning each page.

“Finding the Lindeberg monograph was like finding a secret treasure,” said Koester, who earned a Master of Architecture degree from UVA. “I had already come to strongly believe that the late 1920s marked the high point in American residential design, and to find this resource that included so many remarkably refined and imaginative designs of that period was remarkable. I kept the book checked out continually during my years studying there and memorized it cover to cover.”

“These are solid edifices that seem built to withstand millennia,” says Greg Koester about Harrie T. Lindeberg homes.

Koester – who runs an eponymous residential design firm in Asheville, N.C. — traveled to Lake Forest this summer to speak about the architect inside one of his country houses on Lake Road as well as at the Onwentsia Club, one of Lindeberg’s grandest designs.

That fortuitous stroll through the bookshelves in Charlottesville has served Koester well throughout his career. Early on, he was asked to add on to a Lindeberg home in Long Island to bring it up to modern standards. He even worked on Lindeberg’s own home, which was nestled by the Piping Rock Club golf course in Locust Valley. Around Asheville, he stumbled upon a Lindeberg estate in Biltmore Forest as he drove around in 2002. Believed to be the last Lindeberg home to be in the hands of the original family, the owners gave Koester a 2 1/2 -hour tour.

What makes Lindeberg stand out among architects of American country homes?

“Lindeberg possessed an unusual combination of gifts,” Koester began. “He was certainly a very practical and talented designer of space and planning. His taste leaned toward the simplified and streamlined, but the richness of his detailing revealed an educated and exacting eye and a love for historically correct proportions.

“He was particularly drawn to the vernacular forms of architecture of the places from which he drew his architectural inspiration and took the best possible advantage of the talents of the masons, metal artists, wood carvers and the like who contributed to his projects.”

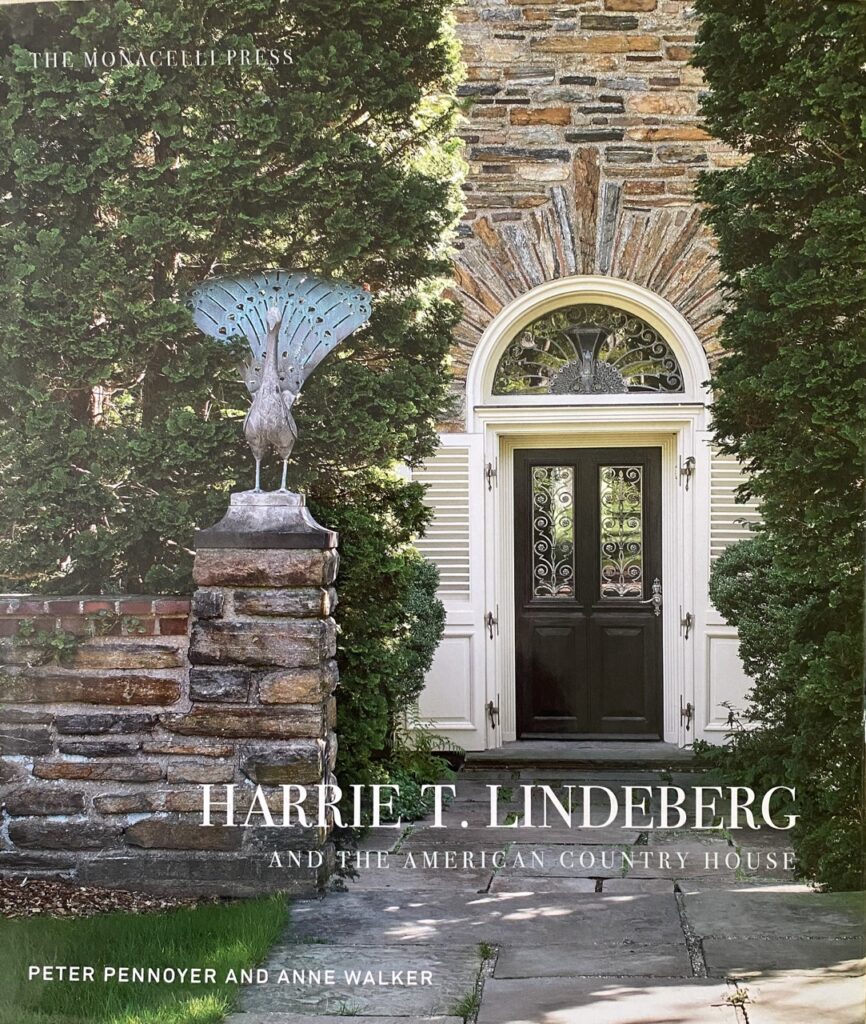

As he toured Lindeberg homes in Lake Forest and one in Lake Bluff (the Philip Armour III estate, which is now the headquarters of Terlato Wines), he noticed the houses shared an unpretentious presence amid their elegance. Indeed, as Peter Pennoyer and Anne Walker point out in Harrie T. Lindeberg and The American Country House, the houses were “meant less as impressive statements of status and more for comfortable living.”

Koester was entranced by Lindeberg’s use of materials.

“All of the houses give one a sense of massive protection. These are solid edifices that seem built to withstand millennia,” Koester noted. “The mixing of brick and stone was one of Lindeberg’s favorite exterior finishes, and all of his houses in Lake Forest play with that relationship in different and remarkable ways.”

Lindeberg – who was born in New Jersey in 1879 and who died in Locust Valley 1959 – was known for his gracious staircases and his high, severely sloping roofs. Early in his career, he joined the esteemed firm of McKim, Mead and White in New York City. He ventured out with a colleague there to create a firm until heading out on his own. Aside from many projects in the United States, from Newport to Houston, he created the U.S. Embassy in Helsinki.

This Lindeberg house on Lake Road in Lake Forest — where Koester spoke this year — has been restored recently.

On the North Shore, Lindeberg is often compared with another well-known architect of country homes, Milwaukee native David Adler. Koester talked about the differences between the two eminent architects.

“Simply put, I believe that Adler was more scholarly than Lindeberg,” Koester said. “His work in so many different styles done with such expertise in each to me reveals serious research at work. Lindeberg might be said to have been a bit more original in his thinking than Adler. He used the historical and vernacular styles in which he worked more as jumping-off points for a more streamlined and modern design language.”

Koester will return to Lake Forest in October to give a talk comparing the two architects on Thursday, Oct. 27 at the History Center of Lake Forest-Lake Bluff starting at 7 p.m. On Saturday, Oct. 29 at 1 p.m., he will present a short film about the Cummings house on Lake Road followed by a panel discussion on the home’s history and restoration efforts at the History Center. Both presentations are a collaborative offering of the History Center and the Lake Forest Preservation Foundation.

Koester can’t wait to come back. Said he, “Any visit to Lake Forest is an exciting visit for me. It truly is one of the two or three best towns in this country for brilliant residential architecture in beautiful settings.”

Unsung Gems Columnist David A. F. Sweet is the author of Three Seconds in Munich. He can be reached at dafsweet@aol.com