BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

“In a city that gave the world a president and a first lady, Monty and Rose became our first family,” volunteer coordinator Tamima Itani said. “With every wing beat, they brought people together.”

The endangered piping plover couple Monty and Rose were celebrated this week on Montrose Beach, site of their own love affair, for their bravery and capacity to inspire a city rocked by a global pandemic and growing crime rates. Although Monty died earlier this month and Rose never returned this year to the beach they shared for three summers, their impact on conservation efforts—and on a city pining for hope—will not be forgotten.

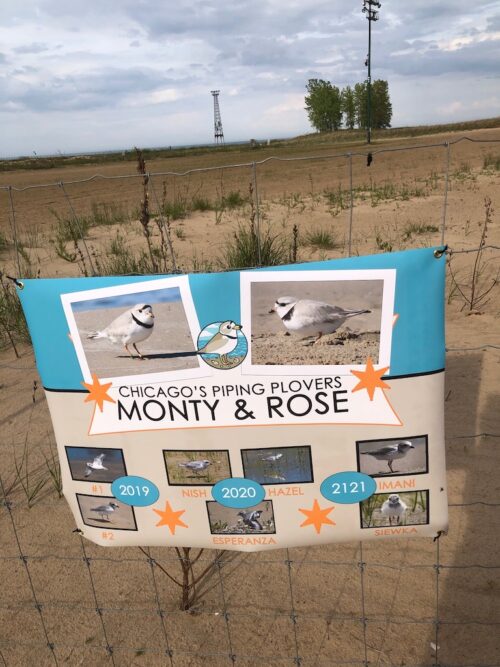

In addition to the hundreds of guests, many in their orange piping plover monitor t-shirts, paying tribute to the two small birds, a special guest was not far away. Amazingly, Imani, their chick, had shown up just days before. (The family of plovers had been banded and thus Imani was easily recognized.) Hatched in 2021, many can recall observing Monty teaching the young Imani to fly last summer.

“Today I saw him scrambling for seeds very close to the same place his father, Monty, died May 13,” shared monitor Daniela Herrera, who had seen Monty in distress and had been with him as he died. “I loved bringing groups of my Spanish-speaking friends here to see Monty and Rose and to hear their enthusiastic comments. I am glad that Monty was not alone when he died. I think he knew that.”

The Lincoln Park Zoo is currently determining the cause of his death and Monty will ultimately be in the collection of the Field Museum.

Because Monty and Rose’s message ties directly to conservation, Itani, known affectionately as “plover mother,” explained: “As much as we want Imani to stay, there are no other piping plovers here and he must breed for the species to survive.” The name Imani, which translates to “faith” in Swahili, was chosen for the young chick when the city was asked to select names for Monty and Rose’s 2021 offspring. In answer to my question if Imani looked like his father, I learned that the tiny circle of color around his neck is much thinner than his parents’ markings.

The signs commemorating Monty and Rose and their chicks interwove the colors of the Chicago Piping Plovers organization with the colors of the bands around their tiny feet. “Monty would do anything to protect his family, chasing off much larger birds, anything that came nearby. He was absolutely devoted to his chicks and Rose. Rose was more tactical and would carefully choose her enemy to target. These were tiny birds but very hardscrabble,” Itani said. “Monty loved people and would come up close, and sometimes you would look down, and Rose would be right there. They had this way of just looking at you.”

Edward Warden, President of the Chicago Ornithological Society, thanked all the volunteers who had monitored Monty and Rose and their chicks in rain, cold, or beautiful beach days. Louise Clemency, supervisor of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, explained, “Piping plovers nest on big, empty beaches without people. Monty and Rose chose to nest in the middle of a Chicago beach, with people, and volleyballs, and kayaks, and killdeer, and skunks, and so many things going on around them. But they made it work.”

When it was announced that, going forward, this place will be called the Monty and Rose habitat there was much applause. Volunteers, one as young as 11 when he first started as a monitor, shared memories. Other volunteers chose words like wonderment and mystery to describe what went on there, an amazement that the plovers chose a crowded city beach as their summer home, often arriving the very same day from their winter migratory areas: for Monty, Galveston beach in Texas, for Rose, an island off the coast of Florida. A couple of volunteers even visited them in their winter habitats. As the child of parents who did much to preserve the Port Aransas, Texas, habitat for endangered whooping cranes, I felt such admiration for these volunteers.

A “thin space” is a description given to the Isle of Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast of England—it is known as the Holy Island and people say that there is just that thin space between Heaven and earth there. Being with volunteers at Montrose Beach that night, seeing the dunes where Monty and Rose summered and hearing other birds nearby, felt like its own “thin space.” But this one possessing of a serious message that our city can do something so wonderful as to have this urban setting emphasizing protection of endangered species and nature conservancy not only for wildlife but for all sorts of prairie grasses. This is truly an accomplishment for Chicago.

The final message of the memorial was “It doesn’t end here.” Monty and Rose’s legacy lies not only with Imani and their other chicks but also in their lasting impact on the conservation movement.