Former Lake Forest resident Jon Henricks sets the swimming world afire during the 1956 Olympics

By David A. F. Sweet

It’s no stretch to say capturing a gold medal is the dream of every Olympian. But what if you exceeded that dream by winning two — and then went further still by conquering competitors in front of fans in your home country — and topped it off by etching world records?

Decades ago, in a time when the show “I Love Lucy” and singer Elvis Presley counted millions of fans, Jon Henricks accomplished all of that in front of tens of millions on television during the first Summer Games broadcast internationally. The Australian-born swimmer, all of 21, delighted his countrymen in the 50-meter swimming pool in Melbourne during the 1956 Olympics — simply by showing up.

“Our swimmers would walk out on deck, and everyone would stand and cheer,” recalled Henricks, a former Lake Forest resident.

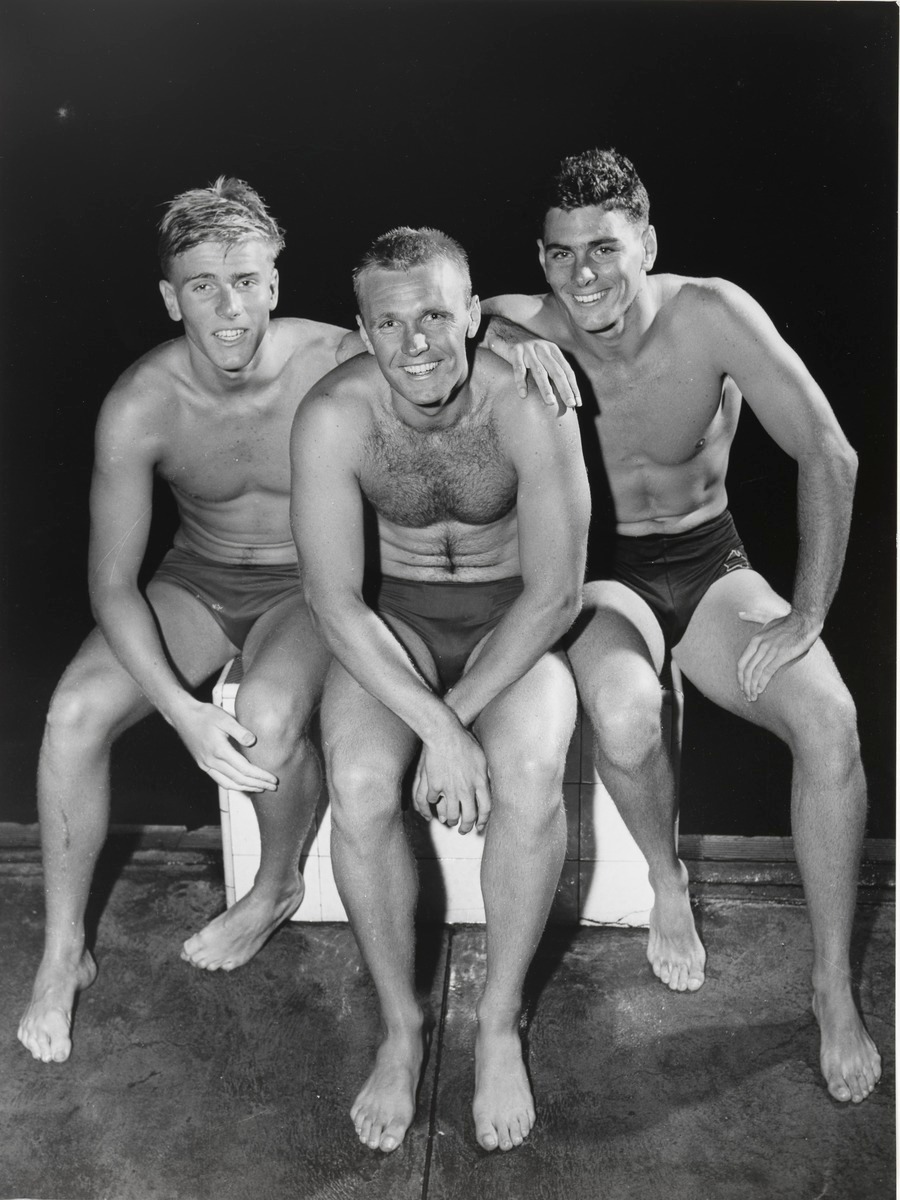

Jon Henricks (center) and fellow Australian swimmers Murray Rose and John Devitt were part of a record-setting team during the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne.

Henricks won his record-setting gold medals in the 4-x-200-meter men’s freestyle relay and in the 100-meter men’s freestyle. In the latter, Australian swimmers John Devitt and Gary Chapman captured the silver and bronze, respectively. The Australian team, in fact, won every individual men’s and women’s swimming event at those Games. Considering in the previous 12 Olympics the country had won 11 gold medals total, the feat was astonishing.

What changed? Now in his 80s, Henricks credits an idea espoused by his father, Clyde. Living next to the Henricks’ family in Rhodes was sailboat enthusiast Don Melrose.

“He worked on the hull of his boat all week, lacquering it, and my father asked why,” recalled Henricks. “He said, ‘By the end of a race, the wind drops. If I find that my hull is clean, I can go a knot faster than anyone else.’

“My Dad took a look at me. I was quite hirsute. He said, ‘Let’s clean your hull.’” Armed with a Gillette razor, Clyde shorn his son of body hair.

Shaven swimmers were unheard of at the time. After shedding body hair, Henricks became a torpedo in the water and set Australian records. A few years later in Melbourne, the entire Australian team — men and women — shaved before meets. Henricks, who had difficulty breaking 60 seconds in the 100-meter freestyle beforehand, credits the practice with shaving (pun intended) crucial seconds off his usual time for his world-record finish of 55.4 seconds in the Olympics.

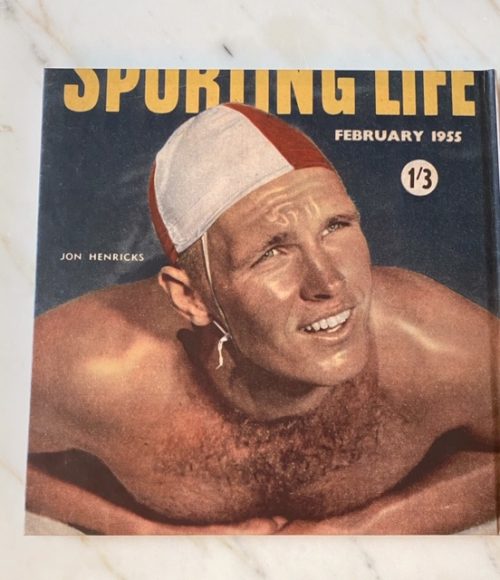

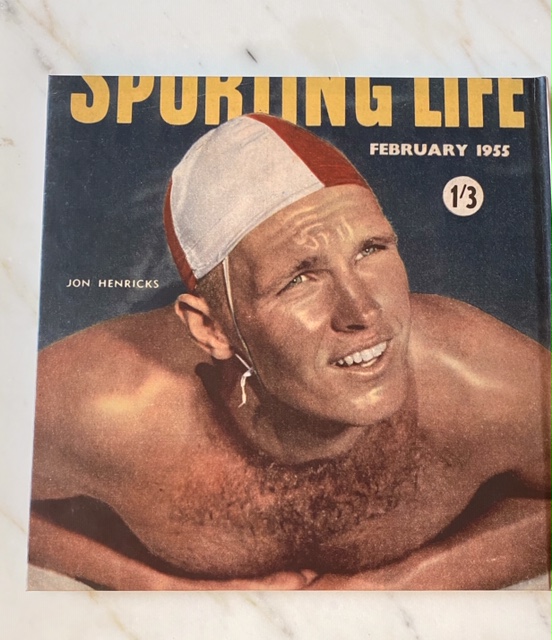

In 1955, Jon Henricks graced the cover of Sporting Life, a magazine similar to Sports Illustrated in the United States. “The Fastest Swimmer in the World” was the headline on the piece inside.

During those Games, Prince Philip invited the young star to watch other Olympic swimming meets with him. His name made headlines around the world. But as Henricks stood on the victory dais, he asked himself: What do I do now?

“My life, to this point, had been devoted to this end,” Henricks recalled in his memoir, Life in Lane Four. “I really didn’t want to spend my entire life swimming.”

The affable Henricks — who peppers his conversation with Australian phrases from his youth, such as “mate” — said he became a swimmer because, like every youngster, he wanted to be the best in some facet of life.

“All of my cousins could beat me at anything,” he said. “At a Boy Scout event, I was asked to jump into a tidal pool, which was 10 feet below. For a little boy, it felt like I was jumping from the top of the Empire State Building.

“After I was in the water, I dog-paddled to the side, and I was quicker than anyone else. I won. My Dad called me Champ. It was the first time he had called me that.”

Henricks started as a distance swimmer in high school. Morning workouts began at 6 a.m.; afternoon workouts lasted 2 ½ hours in unheated, polluted water. He swam 7-8 miles a day — and hated it.

“It was terribly boring and very time-consuming,” he said.

Dejected, Henricks told his parents he didn’t want to swim anymore. But his coach, Harry Gallagher — whom Henricks considered to be a magnificent trainer and psychologist — persuaded him to visit University of Sydney professor Frank Cotton, who measured the rate athletes burned oxygen and monitored their pulse rates. He suggested Henricks forgo distance swimming — which can reach a tortuous 10,000 meters in the Olympics and take two hours — and become a freestyle sprinter instead.

“I was intrigued and excited,” he wrote in Life in Lane Four. “I walked out of the meeting at least a foot taller and filled with resolve.”

After the Olympics, Henricks continued to make a splash at the University of Southern California, as the Trojans captured the Amateur Athletic Union Indoor Nationals with five freshmen swimmers and compiled a number of Pac-8 titles. Amazingly, he was supposed to attend its biggest rival, UCLA.

Ed Pauley, a Bruin bigwig at the time whose name graces the famous basketball arena on campus, hosted Henricks and others for a swimming exhibition at his private island in Hawaii, where the Australian met John Wayne and even conducted a comedy routine with Red Skeleton. Pauley told the budding swimmer UCLA would hold a scholarship for him. But when Henricks arrived in the United States to visit the campus, he called the wrong school, reaching someone at USC. He was picked up at the Los Angeles airport by Murray Rose, an Olympic teammate at USC, and others. He passed standardized tests and enrolled.

“In my naivete, I didn’t know there could be more than one university in a city,” recalled Henricks, who had previously rejected an offer to attend Harvard University. “I was incredibly embarrassed.”

In his 80s, Jon Henricks still swims 1,000 meters a day.

While at USC, a swimming teammate, Mike Wilkie, brought him home to Santa Barbara for Thanksgiving one year. There, Henricks met Wilkie’s sister, Bonnie. More than 60 years later, Henricks is speaking to me from that same Santa Barbara house, where he and Bonnie now live — and where she wears a necklace made from one of his gold medals. Though sickness ruined Henricks’ attempt to win more golds at the 1960 Olympics in Rome (illness also prevented him from qualifying for the 1952 Games in Helsinki), he said he received a much better prize in Italy; he and Bonnie were married there. The Australian and U.S. swim teams formed an honor guard in their uniforms for the bride and groom, and the “Olympic Wedding” was splashed in papers across many countries.

Every day, Henricks swims 1,000 meters without breaks, likely one of the few people his age able to traverse such a distance. With public and club pools in California closed because of the coronavirus, he has been doing laps in his home pool. Despite its easy access, the pool’s length isn’t ideal for a gold-medal swimmer.

“I get dizzy from doing all the turns,” Henricks said. “It’s much more pleasant to swim at 55 yards.”

The Sporting Life columnist David A. F. Sweet can be followed on Twitter @davidafsweet. E-mail him at dafsweet@aol.com.