BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

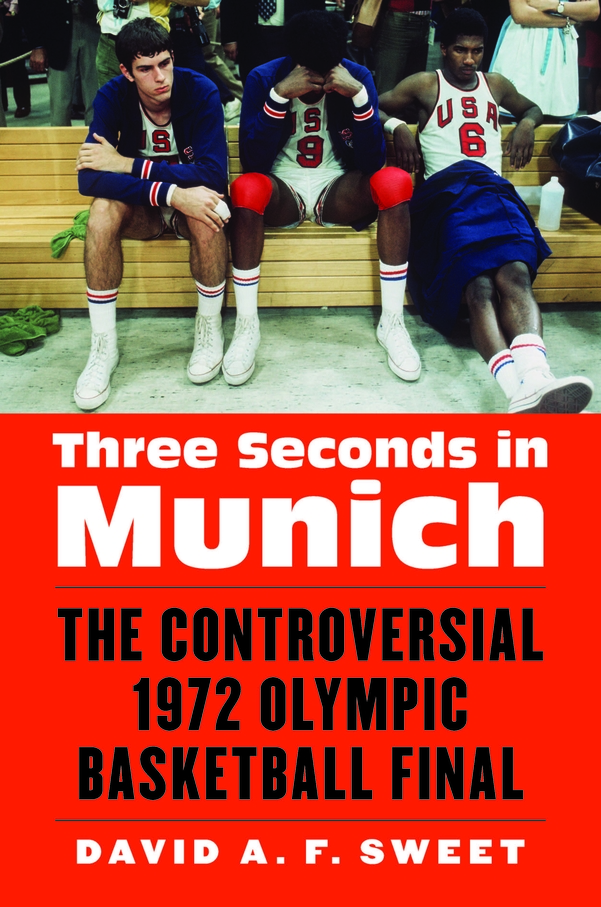

Lake Forest author David Sweet proves that for holding the reader spellbound a final-seconds sports battle beats a cliff-hanger mystery any day. Three Seconds in Munich: The 1972 Olympic Basketball Final, set against the horrific terrorism of the Munich Olympics, recounts the most controversial Olympic game ever—the only one where an entire team refused to accept their medals.

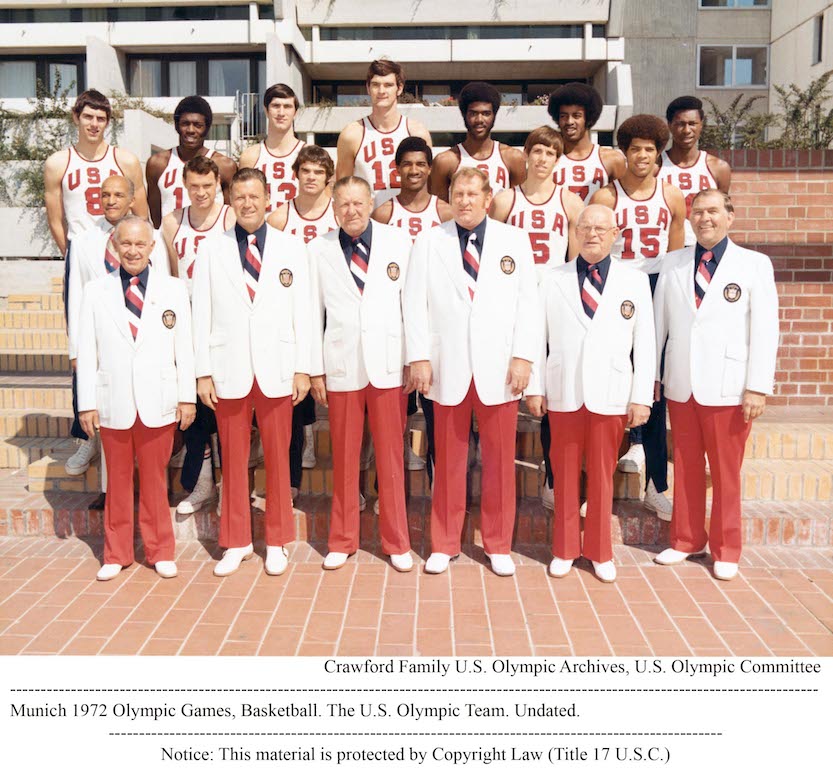

Through Sweet’s interviews with all the living US players who played against the Soviets in the finals, we learn how international treachery robbed our team of the gold and, like other readers, we feel we were almost there in the stands to protest.

“If there’s a message to the book it is to look at these players who, in an obviously corrupt situation, stood for their principles, that at some point you really have to stand up for what is right. The team was unified—and stayed unified—with its decision,” shares Sweet.

“Turning down the medals was definitely a controversial decision, but I feel it was the right decision. At one point, one of the players, Tom McMillan, suggested that if it were ruled that the US team should be given duplicate gold medals they could then sell them for millions of dollars and donate the money to Russian orphanages, but that of course never took off,” he adds.

The book begins as Tommy Loren Burleson, a team member from North Carolina, abroad for the first time, strolls into a packed McDonald’s in Munich on September 5, 1972. At seven foot two he is the tallest of the US players, a person whose life is forever changed that night on his way to the Olympic Village: after mistakenly taking a shortcut through a parking lot, a West German guard puts a gun to his head, telling him to face the wall.

“I heard the Israeli athletes around the corner and looked the main Palestinian terrorist right in the eye,” Burleson told Sweet. “I could hear crying and sobbing—I think one of hostages was hit by a terrorist because I could hear a moan or a cry of pain. They were walking, to their deaths.”

Burleson had earlier met some of the doomed athletes. Throughout Three Seconds in Munich, Sweet lets the athletes tell their stories, and also relates how victory was snatched from their reach.

The US basketball team, whose unbeaten Olympic streak dated back to when Adolph Hitler reigned over the Berlin Games, believed they had won the gold medal, not once, but twice during the game. It was the third time, as the final seconds played out, that seems as unsettling today as it did in 1972: the head of international basketball, R. William Jones, flouting rules that he himself had created, trotted onto the court and demanded twice that time be put back on the clock. Jones lived with unchecked power, and he allowed the rules, ethics, and norms of the sport to be undermined repeatedly with the game on the line. “Jones was gleeful about the US defeat, saying that the team needed to learn to lose once,” Sweet reported.

A referee allowed an illegal substitution and an illegal free-throw shooter for the Soviets while calling several late fouls on the US team. The outcome was challenged following the game but nothing changed.

Sweet told us: “There was no ESPN then. There were no shows solely dedicated to sports. There were only thee national channels. If Jones did today what he did then, it would be a lead sports story for many days. His life would be dissected on the air, and he would be lampooned and vilified by commentators.”

We talked with Sweet as he prepared to moderate a sold-out panel discussion called “Talking Baseball” at the Gortner Center in Lake Forest featuring legendary Chicago sports figures Bill Bartholomay, former owner of the Atlanta Braves; Hall of Famer and Cubs second-baseman Ryne Sandberg; and sports agent Alan Nero. “I figured we have about a century-and-a-half of experience here,” Sweet said.

Growing up in Lake Forest as the son of Philip Sweet, former chairman and CEO of the Northern Trust and head of the Brookfield Zoo and his wife, Nancy, who chaired many of Chicago’s best remembered non-profit events, David was a devoted baseball fan.

“It was actually 1972, when I was 9, that I got to be batboy for the day for the Atlanta Braves when they played at Wrigley Field,” he said. “I’ll never forget it. I grew up loving to watch the Olympics and now take my three kids to Cubs, Blackhawks, and Bears games when we can.”

David Sweet.

A graduate of Denison who wrote while in college, Sweet received a graduate degree from USC and then edited three newspapers in the Los Angeles area. “I wrote feature stories, high school sports, anything you can imagine, but I always had a passion for sports writing,” he said.

He authored Lamar Hunt: The Gentle Giant Who Revolutionized Professional Sports, has launched columns for WSJ.com and NBCSports.com, and has written for The Chicago Sun-Times and the Los Angeles Times.

Believing that some of best journalists are sports writers whose works are rarely flowery, we asked Sweet about his writing habits: “For me it isn’t about putting in a certain number of hours each day but about being passionate about writing, be it non-fiction or fiction. I have been writing non-fiction for 30 years and believe first and foremost that you have to have a great story to tell. It’s my journalistic background that tells me you have to make every word count.”

Regarding future ideas, he shares, “I am considering writing about sports betting and whether fans should be able to bet while at the stadiums. The topic of brothers who both play sports and how they grew up is also intriguing.”

To a reader of Three Seconds in Munich, it is the rigorous research that Sweet conducted on these young players—most now grandfathers—that is most moving. Although he remained haunted by the Munich experience, Tommy Burleson became a highly paid player for the Seattle Super Sonics. After knee and leg injuries ended his career, he returned to North Carolina, where he sold Christmas trees that aided the impoverished in Malawi, Africa. He also became a missionary there, often put in personal peril as he helped with electrical work at local churches and hospitals.

Sweet writes:

From hearing hostages march to their deaths to saving lives is quite a journey. Burleson holds no grudges and appreciates what he learned from his Olympic coaches. Even though he would later win a national championship, he still thought being designated an Olympian was his greatest athletic achievement.