Chauncey, Lyman and William

Life in late 19th century Chicago was sweet for those in the row of stately homes a few steps south of Adler & Sullivan’s Auditorium Building.

By Megan McKinney

Our Classic Chicago Dynasty series on The Blairs continues from three previous segments in late August and September. These portions, which studied the clan’s relationship with members of the Bowen family, may be accessed through links at the bottom of this article.

While Louise Bowen’s grandfather, Edward Hadduck, was heading west in his prairie schooner from Detroit to Chicago–bride beside him, rifle across her knees—Blandford, Massachusetts native Chauncey Buckley Blair rode alone on horseback, quite likely nearby.

Month after month, Blair crisscrossed territory in Wisconsin, Indiana and Michigan, buying public land and selling it at profit. This he did with meticulous personal research and analysis. Following rough and inexact government maps, he studied the properties, looking for proximity to proposed canals, roads and rail lines that would drive up values. With such thorough scrutiny of the parcels he bought and sold, this Blair—principal among Chicago’s founding generation of the dynasty—was able to accumulate considerable amounts of money before a presidential proclamation withdrew these lands from the public market in 1837.

The historic Blair Arms.

His was already a family with a long and distinguished history. The Blairs are descended from a chain of Barons Chauncy, beginning with Chauncy de Chauncy, a Norman nobleman who arrived in England with William the Conqueror in 1066. Also in their line are Magna Carta barons and such legendary royals as Charlemagne, Egbert, Ethelwolf, Alfred the Great, and King Edward the First.

The silver and sable Blair Arms were granted to a forebear for his bravery by King Malcolm of Scotland. Then, under Cromwell, the Blairs fled from Scotland to Ireland, and, in 1720, David Blair and his 12 children sailed for America, going to Worcester, Massachusetts, where they took part in town affairs and local government. One of the dozen of David’s immediate offspring, Robert, soon moved to the town of Blandford, Massachusetts, where portions of the line remained for five generations.

The First Congregational Church of Blandford, built in 1822.

The Chicago Blairs trace their ancestry to David’s son Robert and the town of Blandford through three siblings, sons of Samuel Blair and his wife, the former Hannah Frary. They were the above-mentioned Chauncey and his brothers, Lyman and William. Each found his way to Chicago separately over a period of time.

Chauncey settled in Indiana, where Lyman had established a grain business in Michigan City, at that time the only location for shipping grain by water to eastern markets. Their firm, C. B. & L. Blair—later Blair & Blair—owned the largest warehouse in the state and built the first bridge pier on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan.

A charter for a 30-mile plank road obtained by Chauncey led to the transporting of grain inland, and much more. When he issued notes on stock in his plank road corporation, he found himself drawn into the banking business—where he stayed. Union Plank Road company notes were accepted by state banks throughout the Northwest and could be redeemed in gold. Before long, he had secured controlling interest in a branch of the Bank of the State of Indiana and become its president. In 1844, he married Caroline Olivia De Graff, who would bear six children. Seventeen years later, the couple moved with their brood to Chicago and further banking for the increasingly amazing Chauncey.

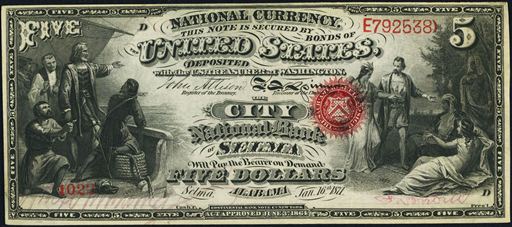

$5 original series bank note printed by Chicago’s Merchants’ National Bank.

In 1865, Chauncey organized and became president of the Merchants’ National Bank of Chicago with paid capital of $450,000. Under his leadership, the bank repeatedly saved the city from financial disaster. Following the Fire, Chauncey made full and immediate payment to all the bank’s depositors, which, to a great extent, restored Chicago’s impaired credit in the eyes of the nation. Because the Fire made it impossible for the city to collect property taxes for the years 1871 through 1874, its credit was further damaged, but Chauncey came to the rescue and, through his advances and faith in the city, again saved its position. And his leadership was consistent through the 1873 panic when he led other banks—most of which had suspended payments—in reversing their policies, enabling the city once more to survive a crisis without serious damage.

Lyman joined Chauncey in Chicago. In 1851, he had married Mary Francis De Groff, a daughter of Amos T. De Groff and his wife, Harriet Sleight, of Poughkeepsie, New York (Although her maiden surname and that of Chauncey’s wife, De Graff, are astonishingly similar, both are correct.) One of the Lyman Blair daughters, Emma, married Cyrus Hall Adams—of the McCormick Reaper family—and the other, Mary, wed Chauncey Keep, becoming a Chicago grande dame. Lyman and Mary Francis were also parents of Lyman Jr. Although the senior Lyman was among family members who were involved in the Merchants’ National Bank, his main occupation continued to be dealing in grain and provisions in his firm Blair & Blair.

Then tragedy struck without warning.

This image of “the clubhouse of the infamous Tolleston Gun Club” appears as murky as the strange incident that rocked the club itself.

When Lyman died suddenly at around noon on September 25, 1883, rumors of suicide swept the city, and, for a short time that afternoon, grain and pork prices fell at the Board of Trade. Almost immediately, however, it was established that the gunshot blast, which blew off a portion of Lyman’s head, was accidental. An avid marksman and member of the Tolleston, a gun club outside of town, he had been driven there by his coachman that morning and gone to his room to pick up a favorite gun; it was there that the incident occurred. Members of the Tolleston Club published an open letter in the Chicago Tribune two days later describing both Lyman’s gun and the accident in detail to dispel lingering rumors that he had taken his life. P.D. Armour, John V. Farwell and John Crerar were among those who attended funeral services in his Michigan Avenue house, where he was eulogized for his great executive ability, as well as his gentleness, tenderness and upright life.

The formidable Blair dynasty had been well established in Chicago when Chauncey and Lyman arrived in the 1860s. Their younger brother, William, preceded them in 1842 and founded the city’s first and largest wholesale hardware dealership, William Blair & Co. Originally a retail store at the corner of Dearborn and South Water Street, it expanded to include wholesale business—so successfully that the mighty Chauncey was sufficiently attracted to it to invest in the operation. Eventually, it was completely wholesale.

In 1854, William married a Lyme, Ohio girl, Sarah Marie Seymour, who was considered a great beauty; their children were William Seymour, born in 1856, and Edward Tyler, the following year.

When William, the elder of the two boys, died tragically at five, the heartbroken couple sold property they had recently acquired in Lake Forest and abandoned plans to build a country place. Their surviving son, Edward, an 1879 Yale graduate, spent his short working life in the hardware firm his father established. When the firm was sold in 1887, both father and son retired from the business, with Edward turning to a life of the mind. The full story of Edward will be reported in future segments; in the meantime, there is more to be told of William and Sarah.

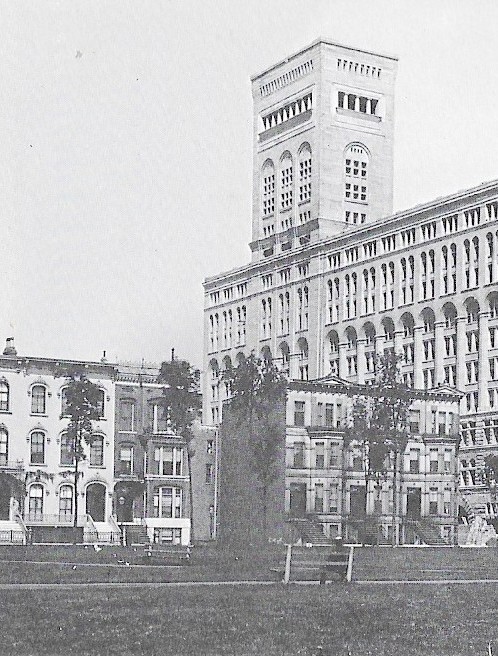

The William Blair house, at 230 Michigan Ave., was one of the showplaces that reigned where the Congress Hotel stands today.

The first William Blair house was, in Sarah’s words, “a three-story-and-basement brick house . . . at No. 111 Wabash Ave., now part of Stevens’ dry-goods store, then a quiet residential district.” (Time has moved on: these words were published in 1919.)

The couple soon built the Michigan Avenue showplace that would be their home for the next half-century. At the beginning, there was just one other house on the block. “We felt ourselves quite in the country,” Sarah recalled. The 16 by 24 foot parlor, which looked out over Michigan Avenue, and to the narrow park across, was the scene of many social events hosted by the Blairs, ranging from small literary evenings and the annual meeting of the Historical Society to major benefit concerts.

The house, located where we now see the Congress Hotel, was within yards of where the Great Fire stopped in 1871. Only a block north was Terrace Row, the elegant stretch of houses destroyed by the Fire to the everlasting regret of architectural enthusiasts. Also destroyed by the horrific blaze was William’s iron warehouse; however, he began rebuilding while the ruins were still smoking.

Immediately after the disaster, the Michigan Avenue Blair house became a distribution center for clothing to those who had lost everything in the conflagration, and Sarah—assisted by such friends as Jessie Bross Lloyd—spent each day for six weeks receiving and issuing new clothes to less fortunate members of the community.

Twelve-year-old Louise de Koven was in New York staying with relatives when the Fire broke out. Years later, she recalled walking out the next morning to Fifth Avenue where people were running from their houses, throwing clothing on wagons with signs that read, “Give clothes for the fire-sufferers.” Responding to a telegram from her father, she returned immediately to Chicago where he met her at the train and took her to their house on Michigan Avenue.

The family then lived a few blocks south of the William Blair’s house and its members were also untouched by the Fire, but the house was full of people, with as many as 50 sleeping on floors. Like others whose homes were spared, her family welcomed Chicagoans who had lost theirs. Louise smiled generously when these visitors used her pet pony for transportation out to the country or ate her “pet bantams, cheerfully saying they did not mind their toughness.” Although the William Blairs were friends and neighbors, it would be another four decades before Louise’s family joined with theirs, enriching a dynasty that prevails today.

When William Blair died of pneumonia in 1899, newspaper accounts were full of superlatives and of the records he had set. At almost 81, he was one of the oldest residents of Chicago; however, “in spite of his advanced age, he was still hale and in apparently rugged health, so that he was often taken for a man of 60.” His Michigan Avenue house “was said to be the oldest house in Chicago.” Furthermore, the hardware business William Blair & Co., “at the time of its dissolution in 1887, was the oldest mercantile firm in Chicago.”

William’s death was also an occasion for the three brothers, William, Chauncey and Lyman, to be lauded for their honesty and integrity. It had been their boast that, in spite of the remarkable business success of each, “no man ever had suffered through their prosperity.”

Megan McKinney’s series The Blairs will continue in Classic Chicago with The Heirs of Chauncey B. Blair in an upcoming week.

For previous articles in this or other Classic Chicago Dynasty series, Click: https://classicchicagomagazine.com/category/vintage/classic-chicago-dynasties/

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl