There Is No Other

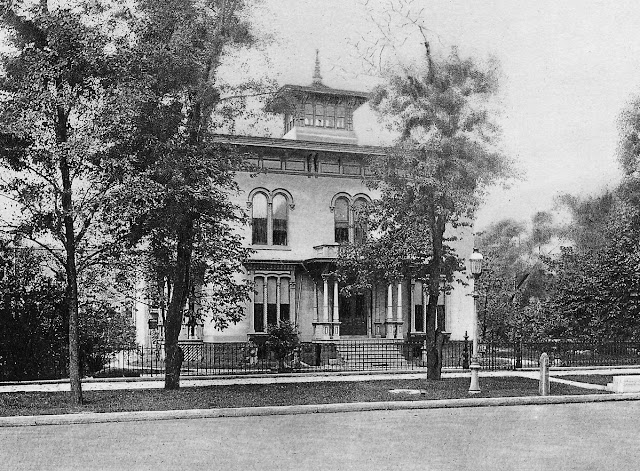

231 South Ashland Boulevard

By Megan McKinney

We consider this to be The West Side Mansion: 231 South Ashland Boulevard, the house in which Bertha Honoré Palmer was raised and Mayor Carter Harrison was murdered.We recently examined with you mansions of the great historic dynasties we “knew” on Chicago’s South and North Sides. Great dynasties. Great mansions.

Now is the time for the mansion this writer nominates as the sole contender from West Side Chicago. First of all, just look at it. Then think of the amazing individuals who lived in it; even those who simply entered it, the still youngish Potter Palmer for one. And why he was there.

Potter Palmer

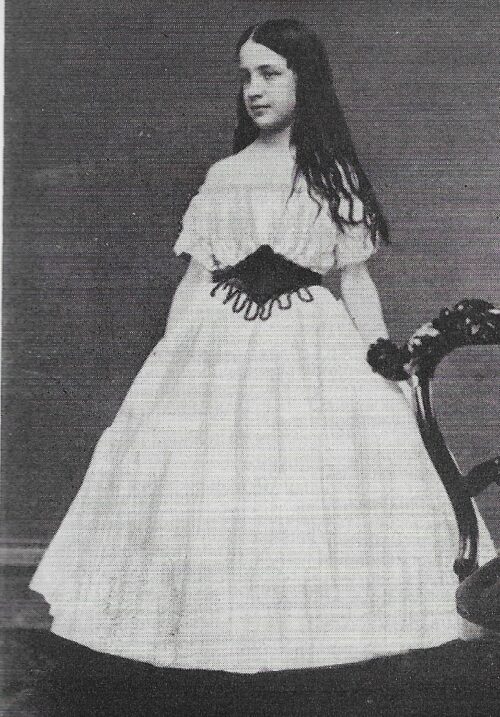

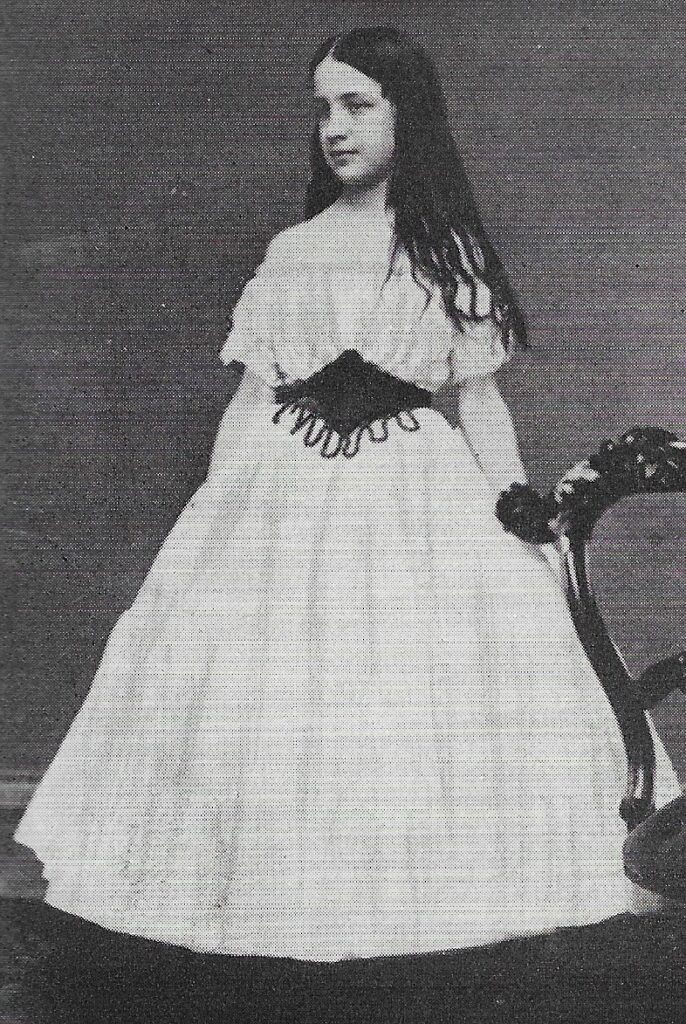

Bertha Honoré then lived in the lovely house with her parents and five siblings. Potter had seen her for the first time that morning as she was entering his Lake Street store with her mother.

The year was 1862. Bertha was 13 years old, and Potter was 36. However, before the mother and daughter left less than an hour later, Palmer had decided that one day he would marry the beautiful, graceful girl, and he set about to begin making preparations immediately.

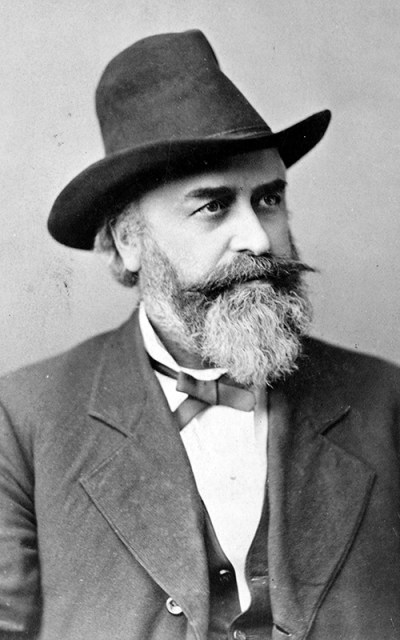

Henry Hamilton Honoré

That evening, Potter called on her father, Henry Hamilton Honoré. His was a social call, but one with a mission, and following pleasantries, he told Mr. Honoré that when Bertha had reached the appropriate age, he would like to call on her. Not only had Potter been struck by Bertha’s beauty, poise and grace, but he also saw in the teenager extraordinary qualities that would mature into making her a superb wife, mother, hostess and companion. And we all know much of the remainder of that part of the story of the great West Side house.

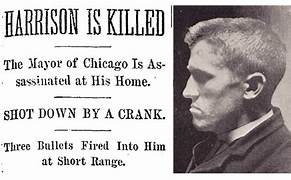

Mayor Carter Harrison was a legendary figure in late 19th century Chicago. He was everywhere, riding into such historic events as the Haymarket Riots on a white Kentucky mare, wearing his signature black slouch hat, trailing smoke from an elegant long cigar.

He was a complex, yet immensely civilized man, a friend of the working man, tolerant of labor unions and lenient about the frailties of others, characteristics that infuriated many of his peers. He was also Yale, Class of 1845, Scroll and Key and fluent in French and German. Soon after graduation, according to his son, Carter Jr., it was off to Europe—and beyond—for two years. He studied art and literature at the Sorbonne, then wandered on to Vienna, Italy, Greece, Constantinople, and enjoyed a camel caravan journey through Syria and Arabia, before returning to his native Kentucky.

alchetron.com

Carter Harrison Jr, who would be, like is father, a five-times Mayor of Chicago.

In 1866, Henry Honoré sold the West Side property to his friend and fellow Kentuckian, the elder Carter Harrison, who would live there for the rest of his life. Following a number of successive years leading his city from the office of mayor, Harrison stumbled in 1887 and was a private citizen for the next eight. In 1891, he again ran, but lost by a narrow margin; however, in 1893, with the World’s Columbian Exposition looming and Chicago a focal point globally, was a time that cried out for his singular style—the dashing man in a black slouch hat on a white Kentucky mare, trailing a stream of luxurious smoke. In April of the year of the White City, Carter Harrison once again ran for mayor of Chicago, and won.

coinappraiser.com

Carter Harrison’s greatest day was October 28, American Cities Day, when 5,000 mayors and councilmen of American cities descended upon the fair grounds at his invitation. October 28, 1893 was also a major day in the life of Patrick Eugene Prendergast, a 22-year-old Irish immigrant—a thoroughly mad young man whose meager employment was supervising a scruffy group of adolescent newsboys whose ridicule and demeaning insults he suffered daily.

‘

credit: murderpedia.org

Prendergast sensed, in spite of genuine insanity, that this was Chicago—a place where, even in the 1890s, political favors would be rewarded with city employment. He had therefore spent more than two years sending dozens, scores and then hundreds of postcards to influential strangers promoting Carter Harrison for mayor. In Prendergast’s deranged view, his postcards had produced colossal success.

However, the city job that Prendergast fantasized would be his, corporate counsel, had not materialized. Harrison had been in the position for six months without returning the favor, or so much as recognizing Patrick’s existence. It was time to seek revenge.

The mayor arrived at his Ashland Avenue home at seven p.m. after a day that had been triumphant, yet so exhausting that he fell asleep at the dinner table. At seven thirty, the doorbell rang, which it often did. This was a mayor who prided himself in being available to citizens at all times. His parlor maid Mary Hanson answered and told the caller to return in a half hour.

When the bell rang again and Mary again answered, she asked the same rather seedy young man to wait in the hall. She went to get the mayor, then returned to the kitchen to join the other servants at dinner.

Harrison’s son, Preston, upstairs in his room, heard a noise, went to the upstairs hallway and saw smoke wafting from below. Looking down, he saw his father lying on his back, the servants clustered about him, and shouted, “Father’s not hurt, is he?”

“Yes,” boomed the voice of the mayor, “I am shot. I will die.”

The commotion brought a neighbor, William Chalmers, who put his folded coat under Harrison’s head. Seeing no blood, he argued that the mayor had not been shot over the heart as Carter maintained.

“I tell you I am: this is death,” Harrison insisted, moments before his heart stopped.

“He died angry,” said Chalmers, “because I didn’t believe him. Even in death he is emphatic and imperious.”

Meanwhile, Patrick Prendergast had slipped away. He was walking toward the Desplaines Street Police Station. “Lock me up,” he said to the desk sergeant, “I am the man who shot the mayor.”

Patrick Eugene Prendergast.

The murder of Carter Harrison cast a monumental impact, blanketing virtually every portion of the city with a shroud of pall. The closing ceremony for the World’s Columbian Exposition was canceled, replaced by a memorial ceremony in the fair’s Festival Hall. “Hail Columbia” became Chopin’s “Funeral March.”

Author photo: Robert F. Carl