By Francesco Bianchini

When prime minister Aldo Moro inaugurated the Autostrada del Sole in October 1964, a good half of the Italian peninsula united in a myth of modernity. From then on, reaching Rome from our house in Umbria was no longer that tortured journey of hairpin bends and ups-and-downs narrated by so many travellers in past centuries. From the tollbooth at Orte, the new highway unfolded in smooth, shiny asphalt across the Roman campagna in a straight run toward the capital, four lanes divided by the exuberance of oleanders that in my memory were perpetually in bloom – white-rose, like sea foam.

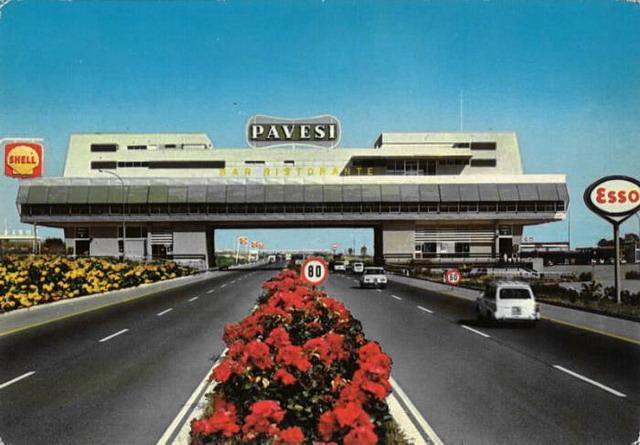

As the car approached the new service area at Feronia – a gas station with a restaurant slung over the highway – we kids in the back seat were gripped by irrepressible excitement. Could we convince Papa to stop there, the one with the huge Pavesino cookie winking on the roof? Alas, only once was the miracle accomplished. Dad parked his Renault-4 under the canopy shaded by bamboo, and we rode up the escalator, then paraded by hedges of stuffed animals and palisades of boxed chocolates. We had lunch right next to the tall glass windows, calmed by the coolness of air conditioning, the discreet sound of piped music, and the delicious smell of so many goodies. Always with eyes bigger than your belly, Mom had scolded as she took half of what we’d grabbed and placed it back in the glass cabinets. In truth, we paid little attention to what we were eating, such was the amusement of seeing cars, trucks, and buses whizzing under us. As I was accustomed to the most frumpy old stuff at home, I found myself in love with progress – and those who casually coexisted with it were surrounded in my eyes with a halo of splendor.

Our Eldorado: the Pavesi turnpike restaurant at Roma-Nord

That first magical experience would never be repeated. My parents seemed to systematically loathe anything that electrified us – yet we kids hoped for another visit with every trip to Rome, starting to whimper and cajole as the restaurant over the highway loomed on the horizon. Dad peered at us through the rearview mirror, I think sadistically enjoying giving us false hope. He’d even reduce speed as he approached the exit ramp, but at the last moment – with a flick of the steering wheel – careen us back on track. Our paroxysm of excited begging died as the car flashed under, like a record player whose power is cut.

On the beach, mamma and me

In summer time, the whole family continued on to the beach at Ostia, leaving in early morning from grandma’s house in Parioli, winding through central Rome and EUR (Mussolini’s Esposizione Universale Roma). There we’d pass by architect Lorenzo Monardo’s ‘mushroom’ with its tower-top restaurant – for us another mirage destined only to be admired from afar. The Renault-4 would queue on the crowded Via Cristoforo Colombo with us kids squeezed between duffel bags full of beach necessities and thermal bags of drinks and snacks. Cars, vans, Vespas and swarms of bicycles raced along the straight stretch of two-lane road, lemmings shaded by maritime pines. Almost unknown was air conditioning, and everyone drove with their windows down because of the morning mugginess. Neither did we have a car radio, but the ditties of Mina Mazzini and Edoardo Vianello reached us anyway from other vehicles, mixed with the screech of cicadas.

The stretch from Rome to Ostia

We’d tumble out of the R-4 at La Vecchia Pineta, the iconic white building, all curves and maritime portholes, built in the 1930s to attract an upper-class Roman clientele. I doubt my parents could afford it at the time: we frequented it on the cheap only because of a season ticket of a cousin of my father’s who rarely came there, and invited us to take advantage of it. Poor Papa would dismount from the car with sweat already pouring from his armpits, but for us kids there was the eagerness to get first onto the beach, not to miss a single moment of the diaphanous, glittering sea.

The exclusive bathhouse, La Vecchia Pineta

If you arrived early enough the beach was immaculate and combed, and the attendants handy to open the changing cabins and place your chairs and umbrellas. However, we who’d drunk lattes and eaten rosetta buns with butter and jam at grandma’s house were maddeningly forbidden to get into the water until the fateful hour of eleven o’clock. Asked why, Mother cryptically replied ‘because two and two does not make three,’ yet it was a pleasure to see her happy at the beach. Despite four pregnancies – with more to come – she was still tall and slender, sometimes showing off in a new bathing suit, with her long and straight hair like Françoise Hardy, or pulled into a stylish French twist – so different from the many ladies with clouds of cotton candy on their heads.

Still of Pineta’s beach from the 1950 Marcello Mastroianni’s film, Sunday in August

After policing our interminable wading, Mom would slip on a swimming cap and, with Dad, jump onto one of the paddle boats and row out to sea with rhythmic strokes. We, still bereft from any prolonged immersion and buried in the warm sand, watched the two of them become tiny dots. Their return was the signal for lunch, and except for the rare times that – zested with salt sticking to our skin and in our sun-bleached hair – we’d go inside to the Pineta’s posh restaurant to gorge ourselves on clam spaghetti, fried fish and gallons of sparkling water. More often, however, Mom doled out split rosetta buns, stuffed with mortadella. One bite and already we were doomed to wait another three hours for the next swim.

Rosetta with mortadella