By Francesco Bianchini

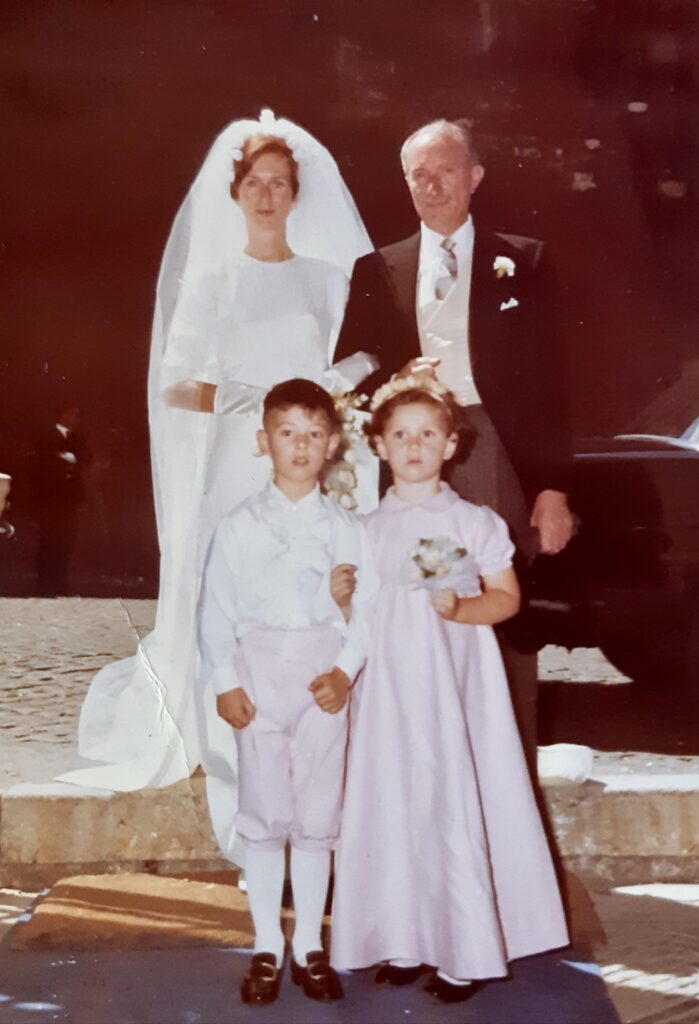

I have a phobia of weddings. People who know me know this, and withhold their invitations. When I was a child I manifested my aversion by sabotaging in my own small ways the ceremonies to which I was dragged, if not actually forced, to participate as a page – usually dressed in a silly velvet costume. Thus I had opportunities like stepping on the bride’s train to make her tug at it, or pulling her veil a little left or a little right, like a bridle strap on a horse. My most daring feat was to pluck the sugared almonds out of the vulgarly tall multi-tiered cake. Too late they would realize the theft, and the cake was displayed for all the world to gasp at gaping holes in the pastel and frothy plaster.

Rome mid-1960s. Disgruntled page. With my brother Filippo (right)

Of my six brothers and sisters, all younger than me, those inclined to be married have done so, and so that danger is now behind me. The first brother to take a wife married a cousin, and I remember the pain of then having to wear tails and top hat to the luncheon at my mother’s house, baked by the late June sun because the canopy fell shy of my portion of the table. Then a second brother married yet another cousin, and my father and I arrived late to the tiny family chapel in the middle of the Tuscan countryside after hastily changing our clothes on the side of the dirt road. A procession of other speeding latecomers had whitened us with dust. At the reception held in the garden, a rejected girlfriend told us the dolefully complicated story of how she’d let that brother ‘slip away’. In due course, my two sisters also got married – thankfully for our genes, to complete outsiders. Playing oldest brother, I endured not only the actual rites but also the two’s exasperating array of emotions, endless shilly-shallying, and obscenely expensive preparations. Then I found myself sitting yet again at the table of the same ex-girlfriend who was impelled to explain again all the (good) reasons why she hadn’t become my sister-in-law. The youngest brother had the better idea of skipping formal ceremonies altogether and chose a simple civil union – and another brother, to close the account, has never married.

Rome late 1960s. Been around twice. With my cousin Margherita

Come to think of it, there was only one wedding I went to light-heartedly with every intention of having a good time. It was years ago, at the turn of the millennium. My mother had accepted the invitation of a French cousin whom she hadn’t seen in quite a while, and who was staging his daughter’s wedding southeast of Lyon. My sister Sabina and I accompanied her. We left Italy on a sunny June morning in mamma’s Fiat Panda. She had never fixed the defective trunk lock, and I still remember the torment of having to press the button repeatedly to get it to open each time we loaded or unloaded our suitcases. We spent our first night in the Italian Alps, the guests of a cousin who housed us in a wing of his palazzo. That evening my mother stubbed her big toe on the leg of a dresser, and at the wedding had to relinquish the shoes she’d brought to wear; she limped, leaning on the arm of each of us. It is why we say the whole thing started off on the wrong foot.

The gracefully forlorn castle of my French cousins in the Ardèche departement

After the ceremony we headed for the chateau owned by the bride’s family. Everything seemed to be in the right place: the imposing and tame character of the large country house, the double staircase leading up to the main floor with the enameled vases overflowing with geraniums, the sloping view and the immense trees that cooled the bright, almost summery evening. I didn’t know anyone except for those rare cousins who, years ago – when they looked nothing like they currently did – had come to spend their vacations in Italy. My sister, on the other hand, had spent summers with cousins in Burgundy and Corsica in more recent times, and was therefore more connected. In any case, we enjoyed the privileged status of rare goods – les cousins italiens – and for a while everyone wanted to talk to us, touch us to see what we were made of. In the meantime an aperitif was served on the terrace. Adults were given champagne and children were served sparkling apple juice. A torrent of kids went around trying to sip the glasses left unattended by distracted grown-ups. Trays of assorted appetizers began to circulate. I particularly remember bacon-covered plum rolls that tended to slip out of my hand and land in very inconvenient places if I didn’t dodge the trajectory in time. I wasn’t the only one – I’m sure – to reflect on the unnatural pairing of plum and bacon, and the friction exerted by their antithetical bodies, despite the fact that a toothpick had nailed them in place.

Bride & groom (Sofia and Michele) in the center, surrounded by her siblings and niece Margherita, Filippo, Sabina, me, Federico, Fabrizio and Stanislao. September 2003, Monte San Pietro, Umbria

We were invited to sit down for dinner. We climbed the entry stairs, crossed a couple of salons, and came out into an inner courtyard where a striped tent had been erected over a multitude of tables. Along with my sister I was seated if not with the teenagers, at least with the youngsters, while my mother sat among the elders at a considerable distance – but I could see the bird with the exquisite plumage that had made its nest on her head, popping up and down all through dinner above everyone else. After a decent Camargue rice salad, there came chicken with mushrooms. The dish undoubtedly had a more sonorous name – poulet de Bresse à la crème et aux morilles, or something like that – but it was still chicken with mushrooms, and my sister and I exchanged looks because of what we’d always heard said about a ‘mushroom wedding’.

The guest bathroom was at the end of a hallway under the grand staircase where delicate spider webs swayed on high. By mid-evening, the toilet was in desperate condition and there was no way to lock oneself in. Fatally, while I was expelling champagne and assorted wines, a girl pushed open the door, excused herself, and closed it with exasperating slowness. I recognized her: one of my dinner partners. Anxious about what she might have glimpsed, I returned to the table and, as a precaution, began a conversation with the other neighbor. I’d seen him taking pictures non-stop, and thought he might be in charge of the photo shoot. I asked him why he chose such particular angles. He turned red and confessed in a low voice that he was crazy about the maid of honor, and had in fact – under the guise of taking pictures – done nothing but frame her. If the family was really counting on his contribution, they would have a big surprise once the photos were developed.

The awaited moment of the desserts came, and everyone inelegantly rushed to the long table on which the pride of French patisserie was arrayed. In the midst of a triumph of macaroons, I saw a gâteau basque engraved with a glen-plaid motif; a tarte Normande – the still-warm apple ridges dusted with white sugar – next to a raspberry tart; a gâteau mille crêpes with vanilla custard; a mont blanc with steep snowy slopes; an île flottante streaked with caramel, floating in a sea of cream, and a croquembouche as tall as a Christmas tree, and festooned with barley sugar.

The mighty croquembouche

In the hotel where we were staying that night, we didn’t sleep a wink. In the garden below our windows a small orchestra was playing to cheer up the celebratory evening organized by a local golf club. At four o’clock in the morning, amidst the drunken laughter of the few survivors, I could still hear a syncopated version of alouette, gentille alouette. In the morning, in the dining room where we ate breakfast, with dark circles under our eyes from the night before, there was a family council of war: we were not going to pay the hotel bill.

The best was yet to come: my mother, sister and I hit the road back through Provence. It took a week to get home, stopping to steal cherries along country roads, bathing in streams under pine trees to the sound of cicadas, eating ratatouille at farms, and bouillabaisse in the dive bars of the Marseilles calanques. Invite me to your Spring equinox parties, diwali or hanukkah, but please don’t invite me to your weddings.