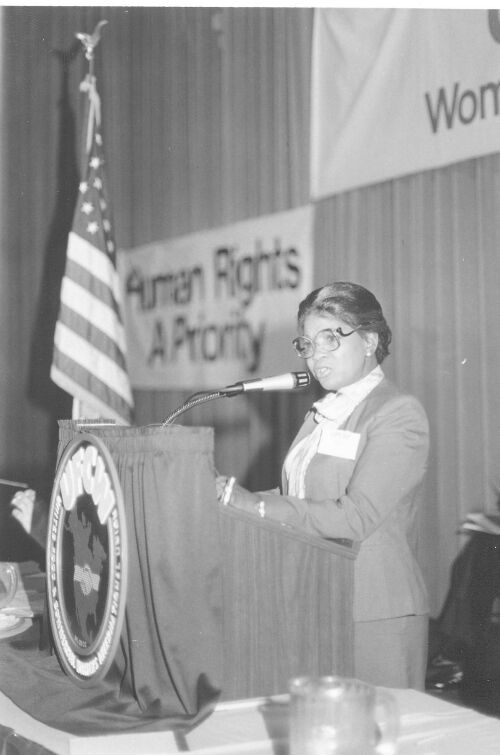

Rev. Addie Wyatt speaking at first Coalition of Labor Union Women convention in Chicago, 1974. Source: Chicago Public Library, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Rev. Addie and Rev. Claude Papers, Box 346, Photo 40.

This Women’s History month we take a look at Addie L. Wyatt, who became a prominent figure of the Civil Rights Movement and one of the nation’s essential Labor leaders. She was born Addie Cameron in Brookhaven, Mississippi, on March 8, 1924. She moved with her family to Chicago in 1930 at the age of six, during the Great Depression. Both of her parents struggled to find steady work during the Great Depression, but both of her parents were skilled tradespeople – her father was a tailor, her mother was a seamstress. Many Southern Black families left the south from Jim Crow and to find better job opportunities. Wyatt was a child affected by the Great Migration. On May 12, 1940, she would later go on to marry her fiancée, Claude S. Wyatt Jr., and raise their two sons. After her marriage, Wyatt was hired as a typist for Armour and Company in 1941.

Wyatt at conference, 1940s; Addie Wyatt speaking at UPWA “Wage War on Poverty” conference, 1040s. Source: Chicago Public Library, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Rev. Addie and Rev. Claude Wyatt Papers, Box 346, Photo 013.

Wyatt soon realized on her first day of work that African American women were not hired as typists, but instead were sent to the canning department to pack stew in cans for the army. She would go on to join the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) during the 1950s, once she discovered the union did not discriminate against its members. As she became immensely involved with labor, the concerns of family and economics were important issues for her; but the fights for civil rights, racial justice, and the women’s liberation movement sharply increased with her new given position. All these struggles organically intersected with each other, and Wyatt once said, “I was fighting on behalf of workers, fighting as a black, and fighting as a female.” She was then named to serve as an international representative for her union, a position she would hold until 1974. As a Black feminist union leader, she was motivated to push for unions to deliberately take a more intersectional approach with workplace issues and organizing a progressively diverse workforce.

Wyatt leaving White House; Addie Wyatt (left) leaving the White House after National Convention on Working Women meeting, 1978. Source: Chicago Public Library, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Rev. Addie and Rev. Claude Wyatt Papers, Box 346, Photo 047.

In 1956, as a program coordinator for District One of the UPWA, her union was the first to invite Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to visit Chicago – to present funds for the Montgomery Improvement Association, which was formed to direct the boycott of segregated public buses in Alabama. “I had to cover five states to raise funds so that we would have our quota… Thank God, we did very well because, number one, I had faith in God, faith in the movement, and faith in the people, white and black, that we were serving. We raised the largest amount of any district in our union,” said Wyatt. In the early 1960s, Eleanor Roosevelt recognized her leadership abilities, she appointed her to a position on the Labor Legislation Committee of the United States Commission on the Status of Women. African American women had the experience of working the floors of meatpacking plants, making them integral to building unions with the aid of Addie Wyatt at the wheel.

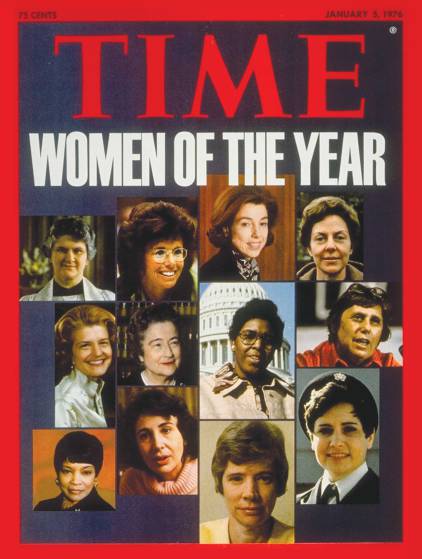

Wyatt’s picture appeared on the magazine’s cover along with First Lady Betty Ford, tennis great Billie Jean King, and Rep. Barbara Jordan, one of the first black woman elected to Congress.

Addie Wyatt contributions helped enriched the lives of women and women of color. Wyatt became the first black woman to hold a senior office in an American labor union, but she is also recognized for her strong leadership attributes. Her influence was vital to the progression on shifting the public on how they viewed women and women of color, women could be seen as strong members and proponent leaders of society. Wyatt was named one of Time magazine’s Women of the Year in 1975, the publication recognized her for “speaking out effectively against sexual and racial discrimination in hiring, promotion and pay.” Wyatt was inducted in 1983 as an Honorary member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority. She was also elected as Ebony magazine’s 100 most influential black Americans from 1980 to 1984. The Coalition of Black Trade Unionists established the Addie L. Wyatt Award in 1987. Addie L. Wyatt was inducted as a Laureate of The Lincoln Academy of Illinois and awarded the Order of Lincoln by the Governor of Illinois in 2003 in the area of Religion and Labor.

Wyatt’s years spent attending, organizing, and advocating with fellow workers – aligning herself along with underprivileged, overlooked, and oppressed Black women made her a prominent figure in the labor movements. Elevating her fellow Black women and forcing an industry, a movement, and, later on, a world that rarely gave them a second thought to make room for them. Her legacy may entail the work she did on the factory floors, the picket lines, and at the podium; but she also occupies a place in American labor history, sometimes overlooking her story and not talked about enough.

References:

Black history month: Addie Wyatt. The United Food & Commercial Workers International Union. (2020, September 8). Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.ufcw.org/black-history-month-addie-wyatt/

Kelly, K. (2022, January 11). The indomitable rev. Addie L. Wyatt. The Nation. Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://www.thenation.com/article/activism/addie-wyatt-labor/