By Francesco Bianchini

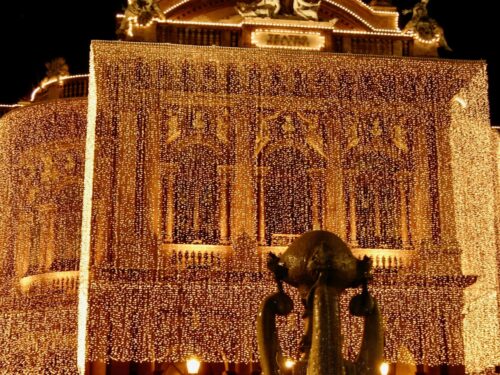

A cascade of champagne bubbles to festively dress up the Teatro Bellini

I have the feeling that I might have eaten more of Sicily than I saw of it. In the two weeks that Dan and I spent in Catania some years ago, there was not a single moment without rain and clouds – nor did Mount Etna once deign to show itself. We circuited the fabled volcano repeatedly, even climbed its slopes, but always clashed with a god both cantankerous and inaccessible. In my memory, Catania was gray, almost black from buildings of lava stone, yet illuminated by its own light: the glare of a metallic sea, the jubilation of its markets at Christmas, the facade of the Bellini Theatre dripping in a shower of lights, the shop windows brimming with arancini (rice balls that are stuffed, coated with breadcrumbs and deep fried), and marzipan; somber buildings enlivened by travertine window frames regurgitating inside with colorful Caltagirone tiles, mirrors, glittering chandeliers, stuccoed walls and ceilings, frivolous staircases as white as meringues. Not the least, the sunlight found in the straight and penetrating gaze of many Sicilians.

The staircase leading to the minstrel gallery (Palazzo Biscari) |

A display of marzipan treats |

As luck would have it, we stayed with Ruggero Moncada, owner of Palazzo Biscari. Although not even remotely comparable to the splendor of the mammoth palace oozing Baroque wonders from which it was separated by a massive door, his guest apartment – with its internal courtyard and view of the harbor – was perfect for us and our two cats, Arcadio and Onoria, who had traveled with us by ferry from Civitavecchia. Ruggero bowed to our every request with the detachment of a great southern lord, and ended up handing over the keys to the palazzo of six hundred rooms so that we might mosey around at our leisure.

Geometries of lava stone and travertine (Palazzo Biscari)

During this first visit to the island I felt myself a stranger and I wondered what an American like Dan might make of it. Our stop in Piazza Armerina was decisive. It wasn’t so much the visit to the mosaics of the Roman villa of Casale – of which I have the dull memory of ugly tin-roofed sheds harboring excavation works in progress, rickety walkways, and totally out of place food stalls crowding the entry path – but of our lunch in a nearby trattoria that sealed it for him. There we both discovered the quintessential Sicilian dish called pasta alla Norma. Since the undisputed protagonist of this earthy and fragrant dish – so little Druidic and celestial – is fried eggplant, I question why it is named for Norma and not Sonnambula, a heroine certainly more carnal and fated, if nothing else to a happy ending. In Sicily I continued to experiment with other first courses, but Dan became so obsessed that he systematically ordered pasta alla Norma at every restaurant, then made notes with the intention of reproducing it at home.

Pasta alla Norma (Courtesy of La Cucina Italiana)

The idea of exporting dishes never convinces me, especially those that are typical expressions of a particular territory. But years later in Paris we found an Italian specialty store that imported fresh buffalo mozzarella, burrata cheese, and the dried ricotta that is indispensable for pasta alla Norma. Dan starts with a tomato coulis, cutting a pound of ripe tomatoes into pieces and sautéing them in a pan with oil and garlic. After about twenty minutes of cooking over very low heat, the tomatoes are put through a vegetable mill and the sauce is reduced for another ten minutes or so. In the meantime, after having drained the eggplant and cut them into thin slices, he fries them in abundant oil, salts them and drains them again on absorbent paper. In yet another pot, rigatoni pasta is boiling to al dente status, and then transferred to the tomato sauce to which a good handful of fresh basil is thrown. The eggplant slices and a sprinkling of grated ricotta cheese are the decor added in each dish of steaming pasta and sauce. As with many regional dishes in Italian cuisine, the ingredients are few but good, and the steps to make them both measured and essential – no guarantee of success; in fact, the easier a dish seems to prepare, the less certain the end result.

The Versailles of Catania (Ballroom in the Palazzo Biscari)

During the holidays, we visited the fish market next to the cathedral of Sant’Agata. Huge mounds of silvery fish were constantly being haggled over, plucked up, and replenished; tangles of tentacles; dazzling mountains of squid, and succulent cuttlefish, into which the fishmongers plunged their hands while shouting to customers; vats filled to the brim with molluscs, urchins and crustaceans; the white marble of the stalls reddened by the blood of tuna and swordfish sliced with terrifying cleavers, and under the benches, between people’s feet, trails of liquids mixed with seawater ran onto the pavement toward sewer grates. A truculent and captivating spectacle that we watched dumbfounded, forgetting that we were there to buy something. But what to choose, and how to cook it in the kitchenette of our studio apartment without ruining one of those wonders?

Fish market in front of Sant’Agata cathedral

Christmas Day came and we had nothing to eat in the house. We set off on an adventure toward Mount Etna, and at lunchtime stopped at a restaurant on the slopes of it where a banquet was in progress. Someone had cancelled earlier, and we were seated in the crowded and noisy dining room. Of this Christmas lunch, I remember two things: even after a long drive up a winding road through the villages in the foothills of Etna, the volcano remained stubbornly out of view, wrapped as it was in puffs of vapor. The other was the traditional Sicilian cassata that was served at the end of the meal. Knowing its sugary reputation, it would have been characteristic of me to pass it up. Instead, I had a thin slice. It took a good twenty minutes to get the hang of that opulence, prepared with sponge cake, ricotta cream, chocolate chips, royal pastry and candied fruit. Deadly, but worth it.