By Elizabeth Dunlop Richter

“It can seem a little bit distant watching the war in Ukraine on CNN, but talk to the music teacher whose father calls every night from a bomb shelter and hear about the children coming to St. Nicholas who walked 13 miles to a shelter. It is very humanizing and shows we’re all so very connected…”

Josh Hale, CEO Big Shoulders Fund

For Sophia, a sixth grader at the St. Nicholas Cathedral School, the war in Ukraine is anything but distant. On my recent visit to the elementary school, she told me about two of her classmates who had arrived from Ukraine in the last two weeks.

“They’re all really nice. It feels good to help them. They tell us some pretty scary things about it, but it makes us happy that they came here and have a better life here.” Sophia explained that talking about what was happening in Ukraine was very difficult. “It’s definitely not easy for them… [one told me] it’s overwhelming transferring schools,” she said.

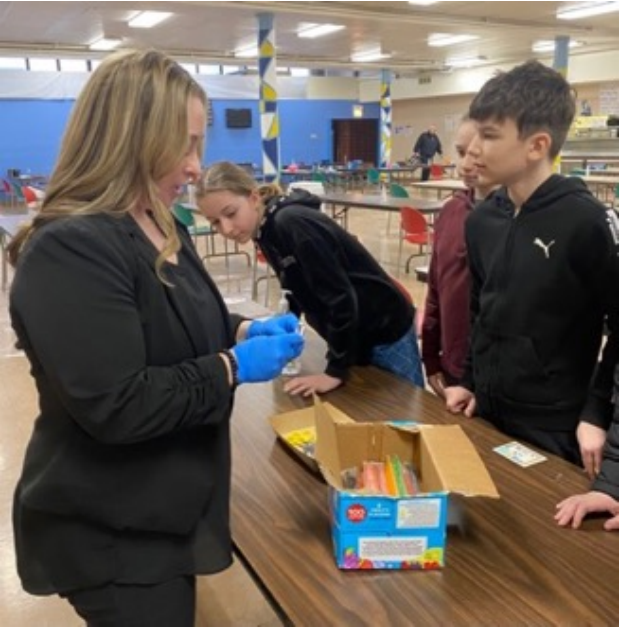

St. Nicholas 6th graders assemble for their hard-earned popsicles. Sophia is second from the right.

The two boys’ families were among the lucky ones who had already obtained visas and were able to leave Ukraine just as the Russian invasion was starting. Sophia, like many of her classmates, speaks Ukrainian and has been able to help smooth the way for the newcomers. I met Sophia and her friends when they gathered in the lunchroom for a special treat: popsicles for reaching a SOAR goal. The SOAR program at St. Nicholas Cathedral School teaches students to be safe, on-task, accountable and respectful. It rewards students for such admirable behaviors throughout the school day in various areas of the school building.

Principal Anna Cirilli rewards sixth graders with popsicles for reaching a SOAR milestone |

Two new sixth-graders from Ukraine get their popsicles |

For Anna Cirilli, the school’s principal on hand to give out the popsicles, this was a welcome break in her hectic schedule. She’s grappling with a nearly 17% increase in school attendance in just a few weeks. Attendance had dropped to 150 during Covid, and now with 31 new students, it has suddenly reached 175. “All I’m doing now is filling classrooms that we already have with staff,” she said. She knows that the number of students will significantly increase in the coming months. “I’m trying to be as realistic as possible. For us to be able to spill into other classrooms, I will need to hire staff and upgrade… Infrastructure is a huge concern of mine [we need paint, new flooring, technology] …My vision is to hire staff for next year when we do start to get bigger numbers.”

Principal Anna Cirilli adjusts her schedule to add a new event

Larger numbers are certainly coming. The United States has agreed to accept 100,000 Ukrainian refugees. Chicago has attracted Ukrainians since the late 1800s and has one of the largest populations of Ukrainian descent in the United States, estimated at 46,000 dispersed throughout the metropolitan area. Some 15,000 live within the city limits. Ukrainian Village, the near west side neighborhood bounded by Division Street to the north, Grand Avenue to the south, Western Avenue to the west, and Damen Avenue to the east, remains the community hub. A variety of Ukrainian institutions, including Ukrainian-owned banks, restaurants, the Ukrainian National Museum, the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art, youth organizations, and both Orthodox and Ukrainian Catholic churches celebrate Ukrainian culture.

St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral

In 1906, a group of Ukrainian laborers raised funds to build St. Nicholas Catholic church. The parish elementary school followed in 1936. The establishment of the Eparchy of Saint Nicholas of Chicago in 1961 led to the elevation of the church to St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral. Today, the cathedral and school operate independently while under the umbrella of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago.

St. Nicholas Cathedral School

Not surprisingly, one of Cirilli’s major tasks is obtaining more funding. The Big Shoulders Fund, a major supporter of under-resourced schools, has been a longtime backer of St. Nicholas, providing tuition for many families, back-office help, training, and recruitment of teachers. In fact, its CEO, Josh Hale, recommended Cirilli for her role as principal at St. Nicholas. . She was working temporarily at Ditka’s restaurant, after having taught in Chicago Public Schools for twelve years and having just returned from teaching in Italy. Hale recounts his first coffee with Cirilli: “I was calling my team from the coffee shop! She told me, ‘I’d work anywhere in an under-resourced school.’ Listening to her talk, I got her loving, caring [nature and] a certain toughness in persisting and finding solutions. As we took her to visit schools and I listened to her, I knew this was a leader starting to bloom.”

St. Nicholas has flourished under her leadership. Hale observes, “She lifted that school up on her shoulders! They love her.” In her seven years as principal, she has worked hard to balance the desire to reinforce Ukrainian culture with the traditions of non-Ukrainian students; the school celebrates Easter by “writing pysanka”, i.e., decorating Ukrainian Easter eggs. At Christmas, children entertain commuters with Ukrainian carols at the Ogilvie train station in the loop.

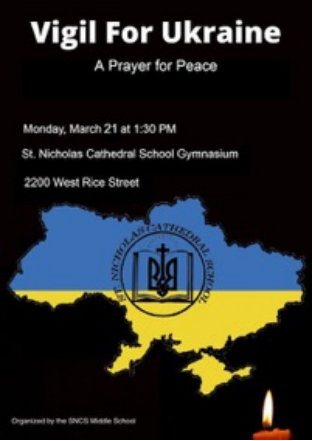

Even before the current Russian attack, Cirilli was impressed with how much her students understood about what was happening in Ukraine. “These students know their history…one student knows 10 times more than what I know… [they understood that Russian] troops have been on the border for some time now… A few days before the invasion, when President Putin gave his first speech, our students told me we need to do something now and organized a prayer vigil. None of us had wrapped our heads around this. We held a second prayer vigil on March 21, inviting other schools. One school brought a check for $2500.

Poster for St. Nicholas’ prayer vigil for Ukraine

March 21 Prayer Vigil photo: St. Nicholas School

In addition to support from donors like these and the Big Shoulders Fund, the school is also the beneficiary of in-kind help. Cirilli explained, “On a recent Thursday we had a group coming from the nonprofit Inspire through Flowers…they brought 100 bouquets of flowers to pass out. People are trying to find a welcoming sign of support.” A corner of the school gym is devoted to a clothing drive for newly arrived families who came with only a suitcase. Teachers and students help sort and fold clothing coming in from retail outlets and families alike.

In addition to support from donors like these and the Big Shoulders Fund, the school is also the beneficiary of in-kind help. Cirilli explained, “On a recent Thursday we had a group coming from the nonprofit Inspire through Flowers…they brought 100 bouquets of flowers to pass out. People are trying to find a welcoming sign of support.” A corner of the school gym is devoted to a clothing drive for newly arrived families who came with only a suitcase. Teachers and students help sort and fold clothing coming in from retail outlets and families alike.

St. Nicholas gym

ira, a Ukrainian eighth-grader in Chicago just one month, helps fold donated clothing.

The City of Chicago is lending a hand to St. Nicholas families through the Fresh Hubs program. The day after my visit, Cirilli met with Mayor Lori Lightfoot at the fresh produce give-away on the west side designed to highlight the need for more access to fresh fruits and vegetables in areas lacking grocery stores.

xxx |

Principal Anna Cirilli talks with Mayor Lightfoot |

On April 9, Chicago Sister Cities and the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art presented a benefit for St. Nicholas School at the Cathedral, featuring Ukrainian musicians and members of the Lyric Opera orchestra and chorus.

Aside from in-kind and financial resources, Cirilli’s biggest challenge is making sure the new students feel welcome. “You want them to feel the joy you feel in seeing them and expressing that.” Cirilli is pleased that many of the school staff speak Ukrainian, including those working in the office and in the lunchroom and the custodians. Her teachers, however, are only bilingual in the pre-school and first grades, where children often have spoken only Ukrainian at home. In the upper grades, over 80% of the students learned Ukrainian at home and act as translators.

St. Nicholas students share a computer.

The story of Chicago is the story of immigrants. Our city’s widely divergent ethnic neighborhoods were established for many reasons by people fleeing poverty, discrimination, and war, or by others attracted by greater opportunity and family ties. Some enclaves have only token remnants of their early settlers, like Little Italy, once filled with Italian groceries and restaurants, where the UIC campus now stands, and Lincoln Park, where a flourishing German community attracted one Frederick Poppendorf, who in 1885 owned the three-flat that is now our home. Today, the spotlight is on Ukrainian Village, sadly because of a war 5,000 miles away.

Ukrainian flag fly in Ukrainian Village

As Cirilli prepares for an influx of refugees, she is comforted meeting the families of the new students. “[Families] come to Ukrainian Village because they know the name, and this is their first stop… They seem happy, calm…that’s the ultimate goal…to make them feel at ease.”

At the same time, she sees their distress at having to accept charity. “They don’t know how to accept things from other people because they had what they needed at home… [One woman initially refused an offer of help and told me] ‘We don’t need it’ and then she started crying…it’s so hard…What’s really scary is that these people are coming from homes like yours and mine. It could happen to anyone.”