By Scott Holleran

Larry Holleran

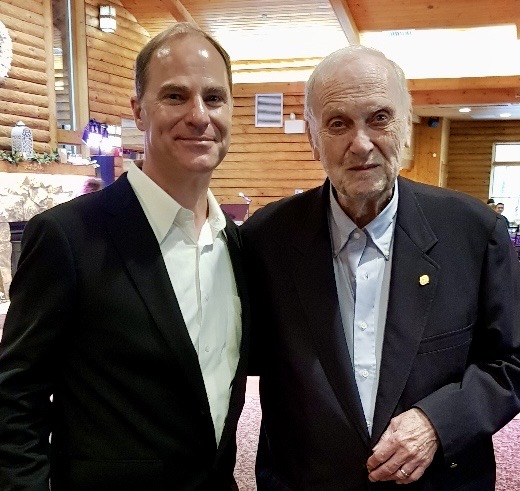

My father, whose job as a businessman brought me to Chicago as a boy, recently died at the age of 93. The Korean War veteran had survived cancer, hearing loss after experiencing shellshock or combat fatigue (today, known as PTSD), diabetes, Ménière’s, various other ailments and infectious and Alzheimer’s diseases, which took him away years ago. My dad was the quintessential self-made American. While barhopping and attending all-boys Catholic school in Pittsburgh as a boy—he’d embellish already tall tales about riding the rails from that steel city to California and getting back in time for dinner—he went to work at the post office and in Pittsburgh’s steel mills. After working as a metallurgist, a semi-pro athlete and studying at a Pennsylvania teachers college, he became a lifelong businessman, coach and teacher, earning a masters degree from University of Chicago and serving as FMC Corporation‘s top personnel executive.

I delivered flowers to Dad at his office in the Standard Oil Building for Father’s Day—my last Father’s Day in Chicago before moving to Southern California—and recall that he graciously placed them on a round table in his office overlooking the city on the lake. Dad was about the age I am now; he was at the top of his career.

Larry Holleran had worked for Crucible Steel in Pittsburgh, Warwick Manufacturing in Niles, and, finally, FMC on Randolph Street in downtown Chicago. He labored at FMC in military and industrial works for decades, negotiating with unions, recruiting, training, managing, laying off and retraining workers and studying plant operations and good work habits during war and chronic economic and cultural turmoil, leading one of the nation’s top companies, mostly under Kenilworth’s Bob Malott. My father rarely talked about being a sergeant in the U.S. Army. My late older brother, Mark, and I pressed him for answers to questions about being a soldier during the Korean War. I broke the ice once, presuming he had been drafted because I knew he’d served before Nixon abolished the draft. Dad angrily corrected me, disclosing that he chose to enlist.

Of course, my dad’s choices redound to his children’s lives, from my appreciation for Johnny Mercer’s songs—which capture his romantic sense of life—to day games in the bleachers at Wrigley Field, attending all-star pro football games—and, later, getting autographs—at Soldier Field and learning that John Lennon had been assassinated while watching Monday Night Football. Besides spectator sports, my affinity for classic television and movies—which led to a commercially successful venture in my career—stems from watching, and also discussing, shows and films together, from the dry melancholy of ABC’s Barney Miller to countless viewings of the brave soldiers depicted in Zulu with Michael Caine and, at the Edens Plaza movie theater, the French Foreign Legion depicted in March or Die starring Gene Hackman. That’s the same theater where we both stood in line on opening day to see Star Wars in 1977.

Art was to be experienced, learned from and thought about—art was to be taken seriously, not merely as a fleeting escape, reprieve or instantaneous thrill. Over the years, we indulged in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera—one of his favorite musicals—as well as Annie, the 1977 stage musical based on a comic strip about an orphan and her dog, and, at a suburban Chicago theater in the round, Julie Harris in The Belle of Amherst, which dramatized one of Dad’s favorite poets, Emily Dickinson. I didn’t like, grasp or relate to the one-woman show and her poetic anxiety. But the performance prompted me to think.

Larry Holleran

Larry Holleran’s interest in literature extended to a range of topics—he gave me several books over the years—including books I discovered on family bookshelves as a boy, which led me to discover and read seminal novels by Joseph Heller, Alex Haley and Ernest Hemingway. I found a volume of Victor Hugo’s Ninety-Three, which became a favorite tale, and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, which I hated, until I read Rand’s other fiction, which won me over me as incisive, scathing and poignant and set me on a journey toward becoming a new intellectual. My dad deserves credit for owning the flashpoint for my writing and philosophy.

The subject that most dominated my father’s leisure reading was war, however, which gives a glimpse into what he was thinking. Whether discussing various views on Patton or MacArthur—whose crossing the border into Communist China in defiance of the American president was a point of contention—he sought to understand weapons, tactics and strategies of war. Years later, while I was reporting on the 50th anniversary of the Korean War, my father took interest in my writing for the first time. I had met and interviewed U.S. Marine and Carnegie Mellon University writing professor Marty Russ, who authored a book about an epic battle between the Chinese army and the U.S. Marines. Later, my interview was linked and quoted in the author’s New York Times obituary; I know my father read and valued the book, which I’d asked Mr. Russ to inscribe to my dad.

Dad traveled back to Pittsburgh to see me speak at Carnegie Mellon University when I was invited to address students about writing, media and Hollywood. Afterwards, we dined at the top of a hill overlooking the three rivers city. Time and again, Dad and I went to the top—often at his house on Wilmette’s Greenwood Avenue where his attic office afforded a view of the brick-laid block—at places across the globe. We marveled atop California’s Big Sur, Mt. St. Jacinto in Palm Springs, the cliffs of Normandy, France for the 50th anniversary of America’s D-Day invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe and the Smoky Mountains near Jellico, Tennessee, where Dad’s foreign car broke down and we spent the night at a seedy motel waiting for parts. We hiked to the tops of Switzerland’s Matterhorn and Mt. Tiede off the coast of Africa. We celebrated at San Francisco’s Top of the Mark.

By then, the former postman and steelworker from Pittsburgh had accumulated a lifetime of planning adventures. Having initiated his first cross-country family trip via Boeing’s 747—my first airplane ride—to Oahu’s Honolulu in the Hawaiian Islands for Christmas in 1972, Dad lived large, sometimes bigger than he could manage. Years later, he confided that he thought I had been killed in the explosion of TWA 800—that same day, I had falsely been informed that he and my mom had been killed in the plane crash, an experience I wrote about in an article for the Wall Street Journal—before we reunited in Rome, embarking on a grand itinerary through Western Europe with my mother. By the end of his life, we had seen the world from Austria to the Redwoods, rode subways in Paris, London and Washington, DC with my former boss Congressman John Porter to Capitol Hill. We toured Jefferson’s Monticello, Disney’s Magic Kingdom and Michelangelo’s David in Florence—and traveled the Glacier Express to the Swiss Alps where we stayed in St. Moritz. We saw the Mona Lisa in Paris, where Dad drove from Charles De Gaulle Airport like a bat out of hell before realizing he’d left the trunk with all the family luggage open while my brother Mark and I laughed trying to get his attention.

Whether at his FMC retirement party in Chicago, at Wilmette Public Library veterans meetings or at his University of Chicago graduation—or at my various acting, speaking, singing, dancing and choreography events on the North Shore, at Park West in Chicago or at Carnegie Mellon—we made the most of life’s momentous occasions.

Scott Holleran with his father, Larry

Dad cheered when I won a dance contest at Neo on Clark Street. When I became the first reporter to meet and interview six year-old Communist Cuban refugee Elian Gonzalez—who was seeking asylum in America—for front page newspaper articles, my father and I forged a bond. For the first and only time, we mutually engaged in activism to advocate for the child’s individual right to live free. After I organized rallies in 13 cities across America, Dad sponsored and marched in a downtown Chicago protest for the boy’s right to be emancipated from Communist Cuba. We lost that battle—the boy was forced at gunpoint to return to the dictatorship—yet we fought for his freedom and never gave up.

My parents had honeymooned in Bermuda, cruised to Alaska, admired America’s heroes at Mount Rushmore, and visited Tokyo, Hong Kong, Seoul and Panmunjom—where Dad made his peace with the ghosts of war—as well as Israel, Egypt and Moscow. They sailed the Queen Elizabeth. They soared on the world’s first supersonic passenger jet. They drove together on road trips across the Great Plains.

As a traveling husband, father and family man, my dad’s finest achievement came during Thanksgiving 2013. Reuniting his children at an airport in Southern California’s San Fernando Valley, we boarded a chartered jet at Dad’s expense for a return to Honolulu, Hawaii. Afterwards, as I disembarked the jet at Van Nuys Airport, I embraced my dad with gratitude. Family can be fractured—more than ever amid today’s cultural conflict—and I credited him for a late stage effort to reunite his family for Thanksgiving. He showed gravitas, chutzpah and can-do Americanism with generosity. This was Dad at his best.

My favorite Chicago memory of the late Larry Holleran came at the top of a skyscraper—downtown’s Standard Oil Building. As an FMC executive headquartered inside the gleaming, white tower on Lake Michigan’s shores, Dad was a member of the Mid-America Club. Being a postman’s son from Pittsburgh who became the first to graduate from college, get decorated with honors in the U.S. military as a war veteran wounded in combat, who read, wrote, managed business, traveled the world with family and rallied Chicagoans around a child refugee from Communism, my father was the essence of a Mid-American—if this means someone who possesses and goes by middle class, Midwestern values, including independence. That night on top of the Standard Oil Building, while I was visiting Chicago, we dined with loved ones, toasting to life with laughter and joy. We felt like we were on top of the world.

In one of my dad’s hardcover novels, Ninety-Three by Victor Hugo, the author describes republican soldier Gauvain as “debout, superbe, tranquille” (erect, proud, tranquil) as he dies in “joie pensive” (pensive joy). It’s a state I like to think Larry Holleran achieved. I discovered these words while reading Ninety-Three, and I came to admire Hugo’s writing partly from a visit to the author’s home in Paris, where Hugo stood at his desk to write, during that trip with my dad. To his eternal credit—often against dark, bloody and confusing times—my father made acquiring these words of wisdom, and the implicit serenity and joie de vivre, possible.

Scott Holleran writes about industry, heroes, culture, ideas and history. The author recently wrote “The Last Statesman” about his late friend, mentor and boss, Illinois Congressman John Porter and “Walt Disney in Chicago” for Classic Chicago. Holleran’s short stories were recently published in new anthologies. Listen to him read his fiction at ShortStoriesByScottHolleran