BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

If you think “dancing in the aisles” is just a phrase, you haven’t seen a performance of Zachary Stevenson as Buddy Holly, the man who changed rock and roll.

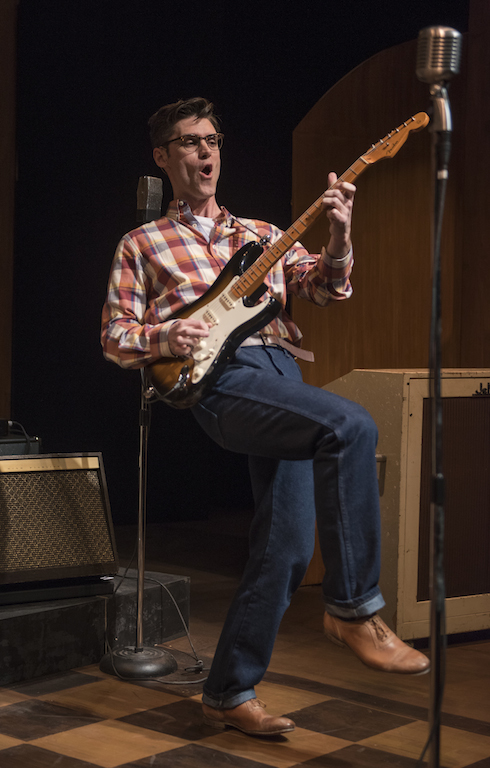

Zachary Stevenson as Buddy Holly.

The Buddy Holly Story , which totally sold out during its spring run in Chicago, has been brought back for summer audiences (through September 15) by the American Blues Theater, and it has already been selling out for the second time this year.

Story proves why the Beatles—who chose their name in tribute to the singer—wanted to sound like him and his band, the Crickets. The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Elton John, and Eric Clapton have all named Buddy, who died at age 23, as a major inspiration.

Stevenson and cast.

Well before the “Rave On” encore, almost when those very first notes of “Peggy Sue” begin, audience members born decades after the bespectacled Texan was killed in a plane crash in 1959 with Richie Valens and “The Big Bopper,” J.P. Richardson, following a concert in Clear Lake, Iowa, are smiling, dancing, and clapping—swept up in the magic that is Zach Stevenson’s Buddy.

Although each cast member romps through the show singing and dancing, showing their skills playing musical instruments from the guitar to the celeste (which gives “Everyday” its magic), it is Zach’s musical magnetism that’s just like lightning.

The Vancouver Island native has played the role countless times, but says he is always learning:

“I have now sung his songs more than Buddy did. I have toured in Canada, playing the role in Ontario, Alberta, and Vancouver, and had the part in Kansas City as well. Every time I come back to the role, I want to refine it. Working with a fresh director, a fresh cast, I get a fresh take on the story.

“If I am not listening, I am not acting. At first I tried to imitate his inflections and his mannerisms, approaching it from the outside. I now have inhabited Buddy Holly I think.”

After performances, Zach comes to the lobby and often listens to audience members’ Buddy Holly stories. The company also visits area senior residences and libraries to perform a few songs and hear remembrances: “Buddy’s music is so powerful and people express their own emotions and memories. The stories they share keep me passionate about the show.”

In talking with Zach, it is clear that he is not only a dedicated actor but also a genuinely nice person—Buddy was similarly known for his sincerity and good manners. He grew up with a musical family on Vancouver Island, learning both classical and popular music, mastering the guitar and saxophone, and playing in the high school band.

Zachary Stevenson.

He is very happy that he and his musician wife, Molly, decided to move to Chicago from Kansas City, crediting our city’s strong musical and theater community. But before moving to Chicago, Zach took a meaningful trip to sites significant to Buddy:

“We wanted to visit pivotal locations such as the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake Iowa, where he last performed on February 2, 1959, before his plane went down later that evening in a snowstorm. The ballroom remains the same. A large pair of thick glasses marks the path to the cornfield where they died, with a small memorial plaque at the site. We visited Lubbock, Texas, his birthplace, and the museum there with his guitar, some of his pairs of glasses and other memorabilia.

“Of all the places we went, his recording studio in Clovis, New Mexico, was the biggest part of his journey and ours. Unlike Elvis’s Graceland, which is filled with tourists, there were maybe only a dozen people visiting that day. The studio raised hairs on the back of my neck—it is exactly as it was when Buddy recorded there. You could sit in the control booth, walk onto the stage—it was very emotional.

“His independent producer, Norman Petty, allowed Buddy to experiment and take his time the way few artists could afford. Because of that opportunity, Buddy became a unique performer. There was a legal debate about who owned what later on, but it really made a difference. For example, the fact that the studio had a celeste, which is like a little piano with a very distinctive sound and Vi Petty, Norm’s wife, knew how to play it, made ‘Every Day’ the distinctive song that it is.

“None of the original Crickets are around, but the brothers of some are still living, and I hope to meet them. Tragically, Buddy’s wife, Maria Elena, had a miscarriage soon after he died, so he had no children.”

We asked Zach where Buddy’s music might have headed if he had lived:

“Buddy never made it to the 1960s, but he sure shaped its music. The Beatles chose a name like the Crickets, and their first demo recording was ‘That Will be the Day.’ The Rolling Stones made ‘Not Fade Away’ their debut song. I think the fact that he was writing and recording with his own chums led the way for groups like the Beatles and the Stones to do the same thing.

“He does show us through his music where he was headed. He was living in Greenwich Village just before his death. That was the scene of the 1960s folk revival, with people like Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, and Phil Ochs living right there, and he probably would have gotten involved.

“Maria Elena was Hispanic, and he was very interested in Latin music. He was producing and selling his own record label at the time of his death.”

In addition to his performances as Buddy, Zach has performed as Carl Perkins, headlined concerts across the country, and directed Million Dollar Quartet. He and Molly love to sing duets: “We like the old time rock and roll of the Every Brothers. We call ourselves the Every Lovers.”

He is currently writing a one-man show about another Texan, the 1960s folk singer and activist Phil Ochs:

“Phil was singing with Bob Dylan in the Village and at the 1963 Newport Jazz Festival, but his career never really took off like Dylan’s did. He was a topical singer, really a singing journalist, and was thought to be a little too controversial. He wrote about the Vietnam War, the draft, civil rights, and labor issues. I am working on a new draft now—Chicago is very fertile ground to develop a story.”

As Buddy.

Don McLean’s “American Pie” of 1971, with its refrain of “The Day the Music Died,” will forever capture the grief and what ifs of Buddy Holly’s death at 23. To Zach, “Buddy was a creative fire. His career lasted for only 18 months. He was really only on the brink of getting started.”

Photo credit (production images): Michael Brosilow