By Lenore Macdonald

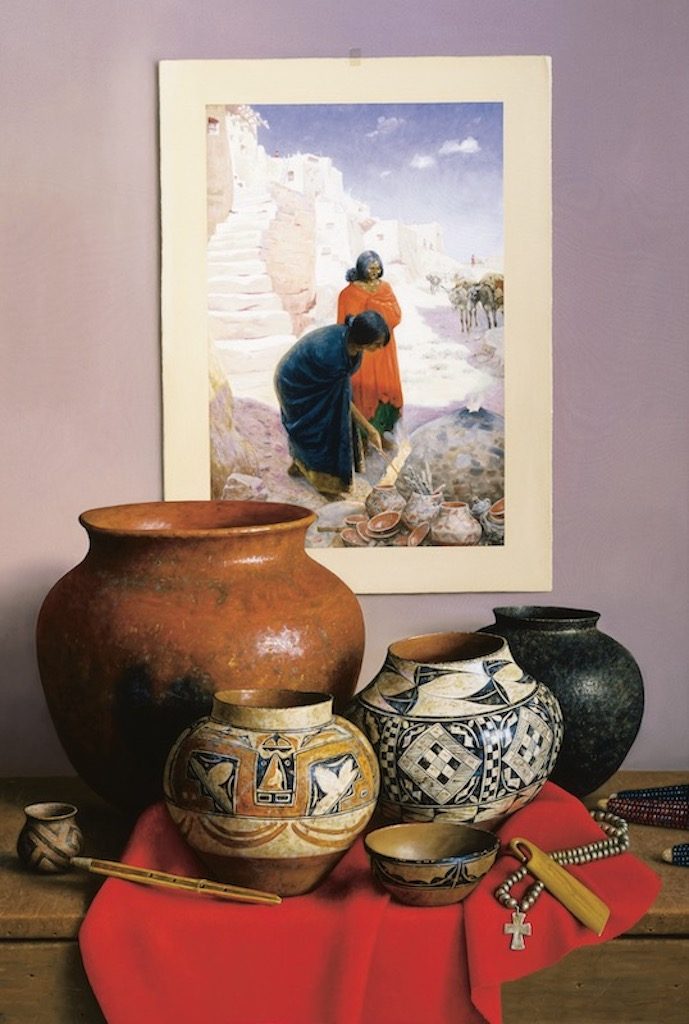

Armed with classical training, he developed a very distinct style that is widely recognized and admired—and copied. He is renowned for his highly realistic still lifes of rich Native American artifacts of the past.

Artists express themselves in many forms. Some artists never get the chance to fully express their inherent artistic abilities, mostly because they have to address life’s quotidian needs and also because they do not ponder how and where best to express their God-given talent. Bill Acheff figured it out.

Southwestern Realism painter Bill Acheff, considered by some to be one of the best living artists today, fell in love with painting in high school, but his career in a barber shop, styling — or perhaps, sculpting — hair during the late 1960s. His painting style was more of an expressive realism, not what the college programs like SAIC were focused upon. Eastern Art Students Leagues did not interest him or he was unfamiliar with them — his artistic sensibilities were very different.

His high school art teachers encouraged him to apply to the Oakland College of Arts and Crafts, but he wasn’t interested in becoming an art teacher. Instead, he was able to study under Italian born and trained artist Roberto Lupetti, who mentored Acheff, always encouraging him to “see your own way. Develop your own style. Don’t copy me.”

An early Acheff painting, before Taos. Silver Pot Lemons and Limes. William Acheff, 1973, oil on canvas, 20×16, Courtesy of the artist, all rights reserved.

Lupetti recognized Acheff’s inherent, natural talent and worked his contacts. Besides a few SF bay area galleries, Acheff sold paintings to Ira-Roberts, Inc., Beverly Hills art dealers. His European, specifically Dutch still lifestyle, was emerging, which he refined and reinterpreted over his career. He would become known as the preeminent Southwestern realism painter, the ne plus ultra of trompe d’oeil.

Acheff recalls that “everything I showed him, he bought.” One of the gallery’s salesmen, Tom, showed Acheff’s work to Dwight Roberts, a gallery owner and artist in Santa Fe. Roberts liked Acheff’s work and thought he would do well in his Santa Fe gallery.

Acheff had left his “day job” to paint full time but was not making ends meet. He knew that he “needed a change and that [he] had to leave California. [He] was looking for inspiration but didn’t know what it was.” He pondered a move to Santa Fe knowing nothing about the area. Continuing to paint in California he finally decided he was ready take up Dwight Robert’s offer and check out Santa Fe (and sold to a dealer to raise cash). He called salesman Tom and said, “tell Dwight Roberts that I’m packed and ready to go to see him.” Unfortunately, Roberts had died. Acheff went anyway. He contacted Roberts’ wife who operated the gallery.

Flapjacks. William Acheff, 1989, oil on canvas. Prix de West Collection, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

Although of Native American heritage, the Southwest was as foreign an idea to him as Mars.

In the mid-1970s, Taos was a sleepy, one-stop-light town. Looking for suitable studio and living space Acheff checked out Taos and stayed. He sent his first paintings back to LA. Immediately they noticed a difference. “It’s the light!”, they exclaimed.

He continued sending paintings west, then with local artists’ encouragement, showed his paintings to Taos’ Shriver Gallery, a beautiful space in artist Leon Gaspard’s former home and studio. At that point, Acheff was not yet painting the Native American subject matter but was intending to give it a try. Something clicked and he realized this was what he was looking for.

The life-changing moment, though, occurred just before a gallery show opening.

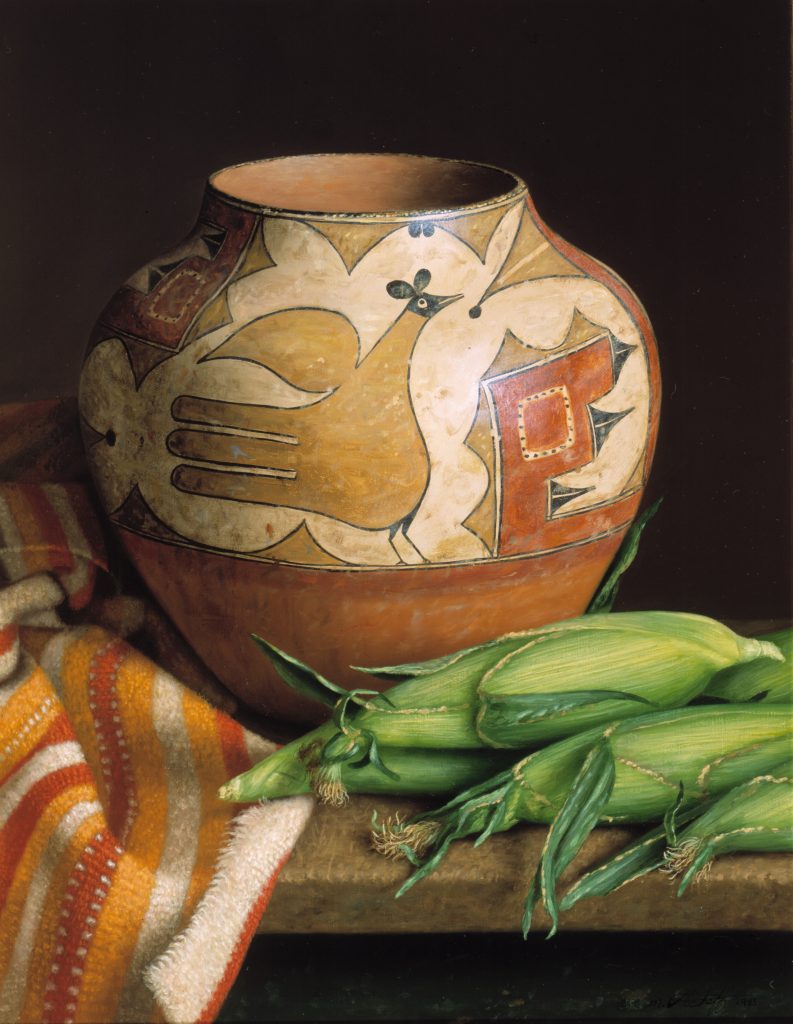

Acheff dropped off two paintings, one’s subject matter was a black Native American pot with corn and a blanket. Shriver loved it. It sold instantly for a mere $425. He sold another painting for $350, the purchaser saying “I’m going to buy this. Someday you are going to be famous.” He kept painting, developing his style, exploring his new surroundings, interpreting the Taos light, and exploring Native American iconography.

Good Corn Season. William Acheff, 1993, oil on canvas. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Museum purchase with funding provided by Persimmon Hill Associates.

Over the next five years, he sold exclusively through Shriver, selling everything produced. They featured his first one-man show in 1978. It was so popular that the gallery had to have its first-ever draw. It sold out. Bill Acheff was getting noticed.

He describes it as “an explosion!”, his eyes illuminated with excitement and wonder, and hands blasting out — and he’s a very low key, soft-spoken man.

Not surprisingly, transcendental meditation is a part of Bill Acheff’s being. He attributes TM to literally changing his palette. In California, his palette appeased collectors. But once he took up TM, colors from his subconscious began emerging. Bill said that “painting is inner. Mediation is inner. My painting expresses that.” Indeed, a sense of calm, awareness and balance pervades all aspects of his being, not only his art.

As You Were. William Acheff, 2004, oil on canvas. Prix de West Collection, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

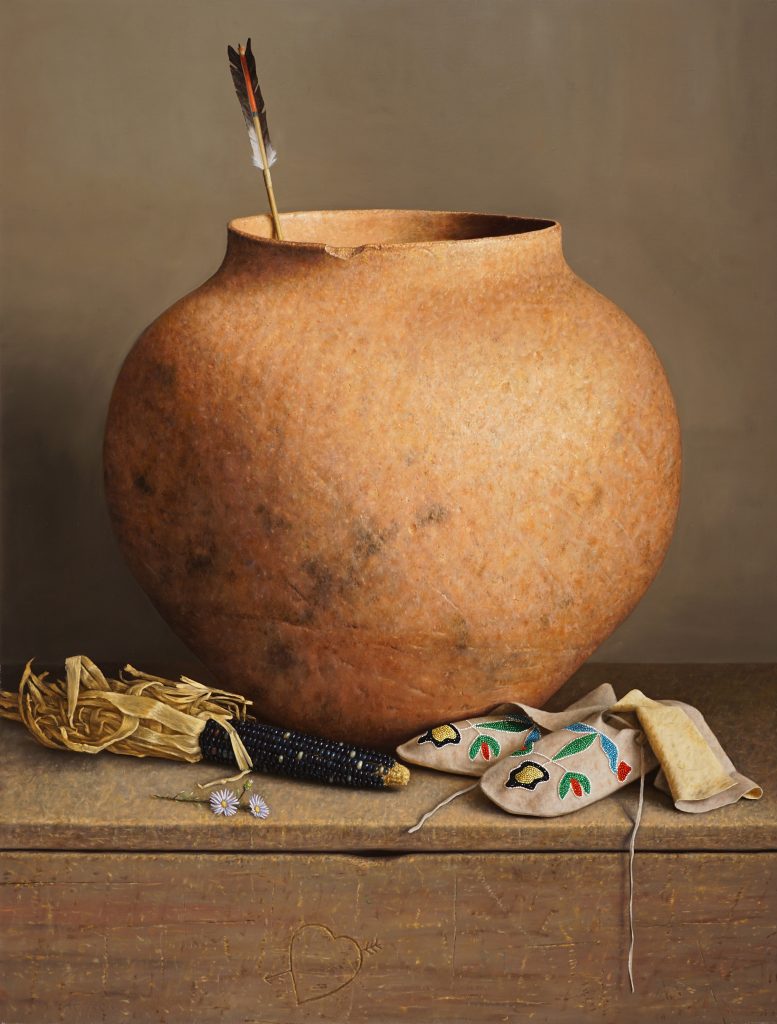

Cupids Arrow. William Acheff, 2019, oil on canvas, 34 x 26. Courtesy of the artist, all rights reserved.

He had gone from cutting hair to painting pictures for Beverly Hills dining rooms to this. He could not keep up with the demand, nor did he, always putting his artistic integrity first.

Acheff shared that he “had no idea what [he] was looking for until he got to Taos and started painting Native American still lifes.” A part Native American himself had finally found his métier and left behind the strictures of Cal. He observed that in California, “Indians were portrayed as a stereotype, but in Taos, Native Americans live on their Pueblo, their ancient home, with strong, ethnic links to the past.”

Coincidentally, and perhaps prophetically, 1981 proved not only to be a breakout year for courtier Ralph Lauren and his homage to Southwestern/Santa Fe Style, but also for Bill Acheff. Or perhaps a bit of kismet — or Taos magic — was at work?

Protecting the Elders. William Acheff, 2020, oil on canvas, 34×26. Available for purchase after August 1, 2020 at the Prix de West Auction, Courtesy of the Artist.

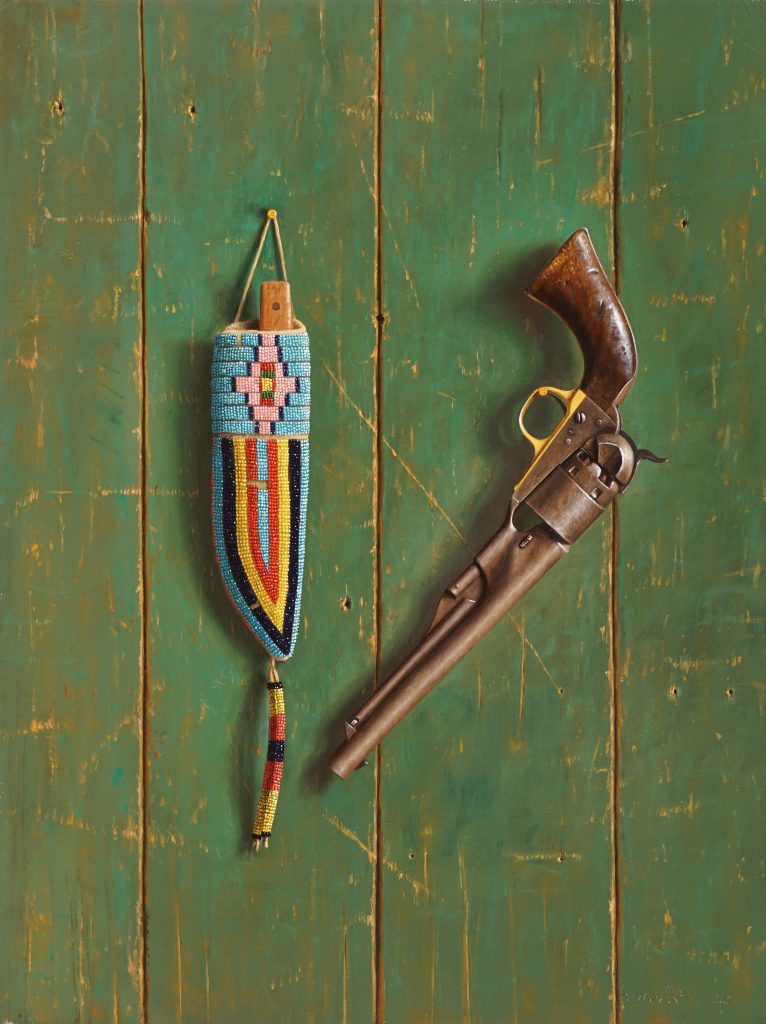

A Gun and a Knife. William Acheff, 2020, oil on canvas, 20×15, Available for purchase after August 1, 2020 at the Prix de West Auction, Courtesy of the Artist.

One of the biggest annual events was Houston’s Western Heritage Sale, an auction and sale sponsored by the likes of Texas Governor John Connally and other larger-than-life businessmen, socialites and collectors, featuring well-established, highly collectible artists like Gordon Snydow, Clark Hulings and James Boren. In 1980, the organizers selected which Acheff painting would be sold at auction; a year later, Acheff selected which one–heady stuff for a 32-year-old.

Acheff pauses, looks out of the window at breathtakingly beautiful Taos Canyon and recalls, “I was deciding which of two paintings to enter. The day of the Preview Party, I decided on a Harnett-style still life, with a violin and bow on the wall, a photo of a yellow rose taped to the left and sheet music to the Yellow Rose of Texas.”

“I flew to Houston, in time for the Friday night sale. At the Saturday afternoon luncheon with the artists, American Quarter horse and Santa Gertrudis cattle consignors (prior to that night’s auction) everyone was asked to introduce themselves. Each one was saying much the same repetitive thing. When my time came, I decided to break up. I stood up and said, ‘I’m Bill Acheff, I’m from Taos, I’m an artist and I’m single’.” Mild-mannered Acheff recalled that, “the crowd clapped, laughed and felt relieved to say the least.”

Did He Say By Easter. William Acheff, 2020, oil on canvas, 5×7,Courtesy of the artist, all rights reserved.

East and West. William Acheff, 2020, oil on canvas, 10 x 20. Available for purchase after August 1, 2020 at the Prix de West Auction, Courtesy of the Artist.

The next evening at the black-tie auction, bidding on the painting, which would have sold in the gallery for $7,000, (he fantasized about $25,000), bidding zoomed past $25,000, stalled at $40,000 before the final hammer came down at $45,000. To thunderous applause, the crowd finally calmed when the auctioneer said to Corinne Fowler, from the Fowler Gallery, “Corinne, are you married?” “No,” she replied. The auctioneer, looking out over the crowd, said, “William Acheff, where are you? We have this beautiful girl who bought your Yellow Rose of Texas painting and you need to meet her. He walked through the maze of dining tables and excited guests and give her a kiss.”

The next day at the Sunday luncheon, Clark Huling’s wife commented to him, “A Star is Born”.

Acheff left Shriver gallery one week before the Western Heritage Sale, continuing to show at Settlers West Gallery, and moved to Santa Fe’s Nedra Matteucci Gallery in the early ’90s. Nedra noted that he has a “special affinity for the historical and cultural artifacts that he chooses to paint. The appealing forms and designs of the Indian pots and artifacts are intertwined with Acheff’s preference for painting textures from nature. The vintage photographs that often appear in Acheff’s compositions help the artist set a mood. Each article in relation to the others becomes integral to the composition as a whole. The results are mesmerizing works of striking beauty” with a mystical luminosity and subtle, intriguing brushwork. His compositions are always intimate and balanced, imbued with calm, symbolism that encourages the viewer to relax, linger, and ponder the elements and the whole.

Ladies Love Flowers. William Acheff, 2020, oil on canvas, 12 x 10. Available for purchase after August 1, 2020 at the Prix de West Auction, Courtesy of the Artist.

Men’s Club. William Acheff, 2020, oil on canvas, 20 x 8. Available for purchase after August 1, 2020 at the Prix de West Auction, Courtesy of the Artist.

After the Western Heritage Sale, he became very busy with big shows and his work was, and remains, in high demand.

Fêted many times over for his prodigious talent, he has twice received, in 2004 and 1989, the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center’s Prix de West purchase award. He also received the Purchase Award, for the first Autry Museum of the American West, Masters of the American West show in 1998.

His paintings are in public, museum, private and corporate collections around the world. Although he still takes commissions, he is extremely generous donating paintings to museum benefit auctions across the country including those at Taos’ Millicent Rogers Museum, The Couse-Sharp Foundation, The Taos Art Museum, and others.

The Year of the Mask. William Acheff, 2020, oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist, all rights reserved.

“Artifacts and traditions of the past,” he explains, “seem to hold more mystical and aesthetic value than those of contemporary times.” And yet, he evolves. Remaining true to his artistic je ne sais qua, he is venturing into new and different subject matter with a new perspective on painting.

He says he is “semi-retired”, but I don’t buy that. He showed me some incredible recent paintings and a stunner in progress. He paints from life, not from photos because “there’s an atmosphere that you don’t get when painting from photographs. I paint the silence of it.” Indeed.

© 2020 Lenore Macdonald, all rights reserved. All images are used with permission of their owners, who reserve all rights.

Like our beloved Chicago museums, due to the COVID pandemic, the annual, highly anticipated Southwestern charity art auctions have been moved online. To view Acheff’s 2020 National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum Prix de West entries, visit https://pdw.nationalcowboymuseum.org/ between August 1 and September 13. The sale is on September 12, 2020. He often contributes works for fundraisers to other museums with strong Native American collections including Indianapolis’ Eiteljorg Museum (auction September 11-12, 2020), the Taos’ Millicent Rogers Museum (November 2020) and the Autry Museum of the American West. Please check those museums’ websites closer to the events to see if he has submitted any works. Acheff is represented by Nedra Matteucci Galleries in Santa Fe, Trailside Galleries in Jackson Hole and Settlers West Gallery in Tucson. His works occasionally come up for auction at Hindman Auctions, Coeur d’Alene Art Auction and others.