By Francesco Bianchini

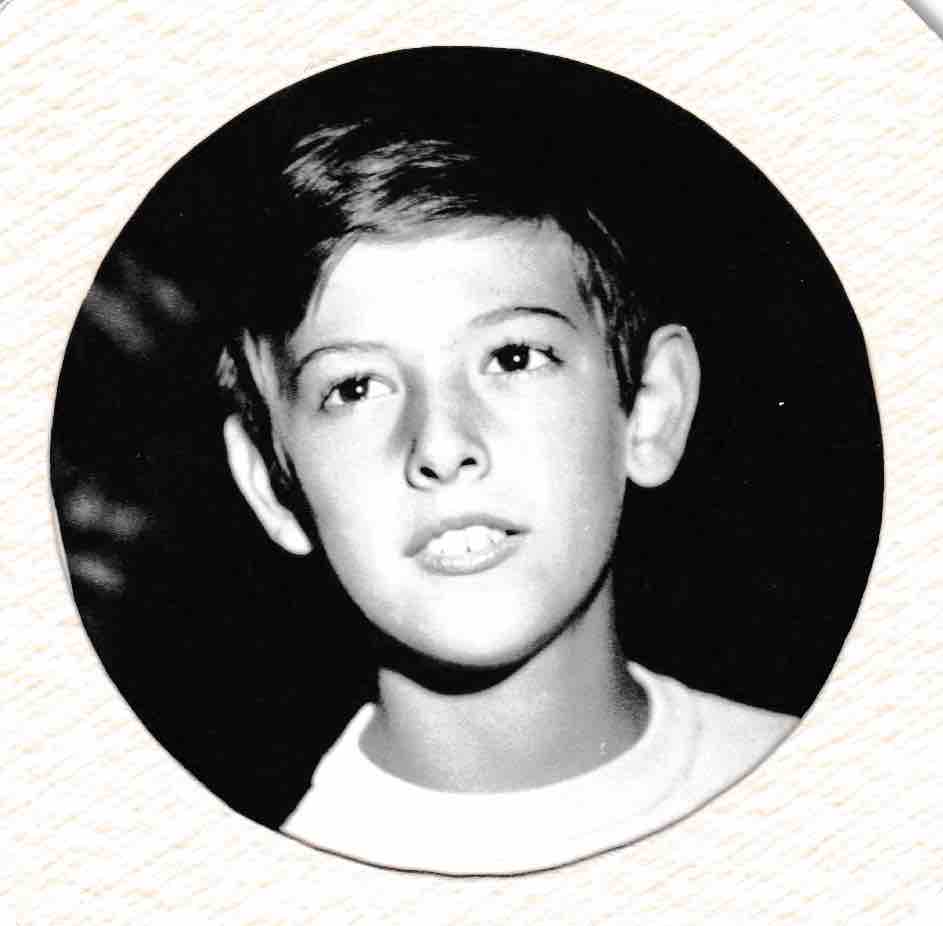

I belong to a generation that was not allowed to throw tantrums at the dinner table, much less get away with it. I had to eat what was on my plate, period. I grew up listening to edifying stories of elegant ladies who perished after eating bad shellfish rather than spitting them out; of ambassadors invited to the table of monarchs who were forced to share meals with good grace that would make one’s hair stand on end. A grand aunt of mine was always pining away for the children of Africa who had nothing to eat. She begged me to finish what I had on my plate for their sake, even though I didn’t understand what was in it for the African children, forcing me to swallow those last, stomach-churning morsels.

The prisoner at the table.

The prisoner at the table.At home we went through culinary ups and downs, and at times things arrived on our table that were barely edible: roast-beef crisscrossed with leathery nerves; fibrous slices of meat; limp and lukewarm salted tongue; smelly stockfish; overcooked macaroni; stringy vegetables. Added to that was my aversion to cheese, and the risk that Augusta in the kitchen might have forgotten to set aside a plate of pasta without parmesan, or that she might have mixed cheese with other ingredients, not telling me the truth.

Since I was not allowed to leave anything on my plate, I devised a few tactics. But hiding the parts most offensive to the eye and palate under my knife didn’t always work. I might be discovered at the moment of clearing the table. It was better to discreetly slide the unwanted bit – which I had chewed for a long time, and that I did not want to swallow – into the handkerchief spread on my lap that I’d empty into the toilet at the end of the meal. For years I sat at the head of the table, which in my house was not a position of respect, but of confinement. Those who sat at the head of the table were served last, or forgotten altogether. The silver lining was that I was less conspicuous, and certain manoeuvers had a better chance of success.

Talking about unpalatable food is quite subjective, I know. It’s one thing to allude to poorly cooked food, or that of low quality, but it’s quite another to recount dishes that are decidedly unappetizing. Once I conquered my aversion to cheese, I made it my duty to overcome parochialism and to try everything. At a cousin’s who lived on a rice farm near Novara, I ate frog legs cooked in milk for the first time. In Abruzzo, I ate snails with and without their shells. In England, I tasted kidney pie. In Baltimore, I experimented with steamed crabs served on long tables covered with sheets of newspaper. Lobsters in Vermont, tossed alive into the pot – never again! But that’s just a matter of ethics; I won’t forget my friend Leslie carelessly throwing the magnificent beasts into the boiling water. In Dordogne, duck and goose in all their incarnations; and I don’t know where I had eel, overcoming my repugnance and likening them to large snakes. Feral-tasting lamb in the Balkans; raw fish in Japanese restaurants; spicy grilled meat, fish, and vegetables in the Mongolian tradition; and only recently coda alla vaccinara – stewed oxtails in tomato sauce – in an unpretentious Roman trattoria. I have to thank my mom and dad, grandparents and aunts all, for opening my gastronomic horizons, and I have to scratch my head to search through my memories of troubled culinary experiences for things truly disgusting. Here’s what I found.

L’andouillette. A French specialty that to define gross is to say little. Although the original recipe comes from Troyes in Champagne, other regions of France offer their own versions. It is a sausage filled with fragments from a pig’s digestive tract, and if that is not enough, know that the word andouille (nitwit) is a title of which no one would be proud. The andouillette is often the queen of village festivals, along with merguez and other types of sausage. This explains why Dan and I unsuspectingly ordered two servings at a flea market. As we discovered when we dissected it, andouillette has a filling that is anything but compact: we contemplated a section of stomach in full digestion, and the aroma it emitted – despite the herbs, spices and white wine – only confirmed the impression. The taste – ‘musky’ as the Michelin guide demurely defines it, ‘has a reputation of not being appreciated by children, women and foreigners’. (I quote verbatim from Wikipedia.)

An inedible andouillette.

Pastilla. In the cottage we rented in Tangier, we were greeted one day by a delicious smell. Amina, who managed our impractical kitchen, was cooking something elaborate, the preparation of which had begun the day before. There were almonds, chocolate, pâte genoise, chicken, and spices, but no one could suspect that the ingredients would all end up in the same dish. Pastilla is a pie made with pigeon meat and served for holiday meals. Since pigeon is often hard to come by, Amina had replaced it with shredded chicken. As we discovered that evening, the pie is a preparation that combines both sweet with savory in the most discordant way; instead of puff pastry that would have mitigated the friction, Amina used pâte genoise, stuffing it with salted meats, cooked slowly in broth and spices, then chopped and mixed with beaten eggs. Everything is encased with a crunchy layer of toasted and chopped almonds, cinnamon, and powdered sugar. We were sorry that this undertaking – which Amina had channeled time, energy and so many goodies with so much enthusiasm and great clamor of pots and pans – had produced such a disappointing result. The pastilla was, to us, uneatable that evening, and did not improve with time. Not to offend her sensibilities, we made the remains disappear little by little in the following days, using it as fertilizer around the orange trees and the loquats in the garden.

Pastilla – the queen of Moroccan cuisine.

Steamed méchoui. It pains me to penalize Moroccan cuisine yet again, but here is another specialty that I found impossible to eat. For Eid, the Muslim Feast of the Sacrifice, sheep, mutton or lamb have their throats slit. The cleaned animals – deprived of organs, and sprinkled abundantly with spices – are usually cooked for several hours in an oven of embers in a trough in the ground, or in an earthen oven, or on a spit. But in Fez, where it is forbidden to have fires due to its urban density as the world’s most populous medina, méchoui is, alas, boiled. My first mistake – made for my love of local color – was to stay in a dar; the typical houses found in the historic centers of every North African town, which were designed somewhat as fortresses, situated one next to the other in dark alleyways. A dar overlooks only its own inner courtyard, always richly decorated with zellige tiles, carved wood, and sculpted plaster panels. The rooms therefore have no windows to the outside. Our cat Arcadio and we found the arrangement anything but congenial. One evening Dan and I went to dinner at a private house that offered traditional medina cuisine. The owners came to pick us up and take us back because a foreigner has no way of getting out alive from that labyrinth of alleys that are often just wide enough to let one person pass. I ordered the famous boiled méchoui which was served to me in pomp with its side dishes and condiments. In spite of its seasonings, the pinkish meat, lined with translucent cartilage and soaked in congealed fat, still exuded the smell of a live animal. I merely nibbled on the excellent accompanying vegetables and – driven by an old automatism – hid the discarded meat under a discreet mat of lettuce.

Boiled goat, mechoui.