BY MILOS STEHLIK

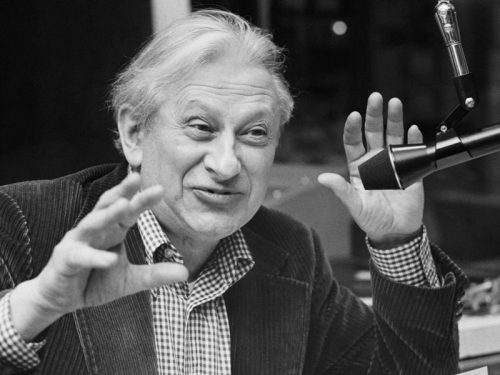

Studs Terkel. Photos by Nancy Crampton.

Studs Terkel was famous for his art of the interview, his many books, his humanism, and for his favored red checkered shirts. He was also a lover of and a believer in the power of film. When he was already in his 90s (he passed away at the age of 96), after he had survived a major health crisis, we started a series of films at Facets which were Studs’ choice. Studs chose the films, introduced them, and led the discussion. (It was then that I discovered two secrets to his long life: he sometimes asked for a quiet space where he went and took a 10 minute nap, and when I drove him home and he invited me in for a drink, the drinks he poured were very much on the generous side.)

John Ford’s “The Grapes of Wrath” (1940).

The films Studs chose reflected his core beliefs: a society in which we accepted and respected each other and in which everyone had an equal opportunity to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Perhaps no film he chose affected him so deeply (even though I’m sure he saw it many times before) as John Ford’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Depression-era novel, “Grapes of Wrath.” Released in 1940, with Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell heading the Joad family as they leave the Oklahoma dust bowl for the promised land of California, the film was nominated for seven Academy Awards. This didn’t matter to Studs. To a packed audience — with an astonishing number of young people in it — Studs rose up after the screening and kept repeating, “This is not about the Depression. This is now.”

To Studs, the need to reach across the divide which separate the haves from the have-nots in the film was real, called for recognition and action. Class divisions and enemies reaching out to others is one of the themes in the first film with which Studs opened his series: Jean Renoir’s masterpiece, Grand Illusion. The “enemies” in the film are a trio of French officers in a prisoner-of-war camp captured shortly after the Battle of Verdun: the aristocratic Captain de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay), the working class Lieutenant Marechal (Jean Gabin) and the nouveau-riche Lieutenant Rosenthal. Moved from camp to camp, they are finally imprisoned in the fortress of Wintersborn, a fortress commanded by the aristocratic Rittmeister von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim). Freedom outranks class bonds between de Boeldieu and von Rauffenstein, as human connection is stronger than wars which separate us; when the French trio escape, they are taken in and saved by a German widow living on a farm whose own husband was killed during the Battle of Verdun. Grand Illusion is a cry for peace, an end to wars.

King Vidor’s “The Citadel” (1938).

For The Citadel, a 1938 film directed by King Vidor and adapted from a popular novel of its time by A.J. Cronin, Studs brought along his longtime friend, Dr. Quentin Young.

The film stars Robert Donat, Rosalind Russell, Ralph Richardson, Rex Harrison and Emlyn Williams. Donat plays a young idealistic doctor treating Welsh minors with tuberculosis in a Welsh mining village. Moving to London, he continues treating working class patients living in abject conditions. In a chance meeting with a fellow school friend, Dr. Frederick Lawford (Rex Harrison), he is seduced in changing his practice to treating wealthy hypochondriacs. This drama about moral choice rings oddly prescient today in which the disparity in available medical care based on economic means is an increasingly glaring issue.

We asked over a hundred artists, filmmakers, writers, film buffs for lists of films which influenced them the most. The structure of that question is telling: not a list of what they consider the greatest films of all time, but films which had a special meaning in their lives.

Studs responded with a note:

Studs Terkel’s note.

“These are among my favorite films. They have affected me now as much as the exhilarated moment I first saw them.

Facets Multimedia has played an important role in my life as the surgeon who saved my life. Milos has offered me and, for sure, millions of others a richness they would otherwise not have.

Studs Terkel ”

Here is Studs Terkel’s list:

Baltic Deputy (1937) directed by Alexander Zarkhi and Josef Heifitz

La Strada (1954) directed by Federico Fellini

Ikiru (1952) directed by Akira Kurosawa

The Bicycle Thief (1948) directed by Vittorio De Sica

RKO 281 (1999) directed by Benjamin Ross

Wild Strawberries (1957) directed by Ingmar Bergman

Grand Illusion (1938) directed by Jean Renoir

The Last Laugh (1924) directed by F.W. Murnau

The Bicycle Thief (1948), directed by Vittorio De Sica.

Wild Strawberries (1957), directed by Ingmar Bergman.

It’s an interesting mix of great classics (La Strada, Bicycle Thief, Wild Strawberries, The Last Laugh) with a couple of not-so-well known titles like the Soviet-era Baltic Deputy or RKO 281. The underlying characteristic which unites them is a deep humanism – the idea that individuals are responsible to and for each other, and deep questions about the meaning of one’s life. In Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru, for example, a film which is deeply moving, a middle-aged Japanese man who has spent his entire life as a bureaucrat, searches for deeper issues of life when he falls ill; in La Strada, it’s Giullietta Masina as a naïve young woman bought from her mother by a touring strongman, played by Anthony Quinn. The idea that people can connect, understand and help each other and that film can open their hearts and show them how to do that is the magic of film which Studs Terkel so well understood.

[You can find all of these films at the Facets Videotheque on DVD or streaming online at Facets Edge – www.facets.org/edge]