The Influence of Prairie Avenue on the 1893 Columbian Exposition – Part I

By Melissa Ehret

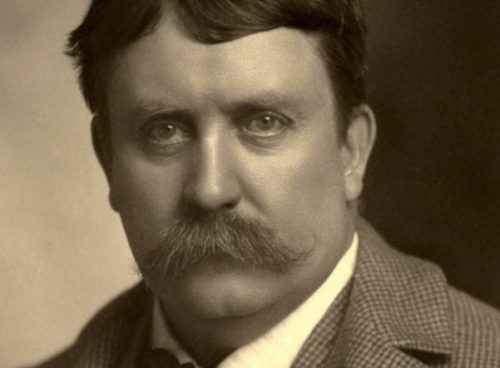

Daniel H. Burnham, circa 1890

“Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that our sons and our grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty.”

This timeless quote is from Daniel Hudson Burnham, the legendary Chicago architect and urban planner. Burnham is the author of the Plan of Chicago, a masterful 1909 text that, among other things, helped ensure that Chicago’s miles of lakefront were not only beautiful, but functional and accessible to all. Burnham was also the visionary behind an event that would establish Chicago once and for all as a world-class city, commercial juggernaut, and cultural mecca: The 1893 Columbian Exhibition.

John B Sherman Home, 2100 S. Prairie Avenue

Like many remarkable Chicagoans profiled in this series, Daniel Burnham was a denizen of Prairie Avenue. One of his first architectural commissions, shared with business partner John Wellborn Root, was a grand home at 2100 S. Prairie Avenue. The fledgling firm of Burnham & Root designed the mansion for John B. Sherman, one of the founding members of the Union Stockyards. While the home was under construction, Burnham met and married Sherman’s daughter, Margaret. At the outset of what would be a long and happy union, Burnham came to live in the house he built for his eventual father-in-law. Sherman became an avid supporter of Burnham & Root, using his many business connections to generate commissions for the growing firm.

During his time on Prairie Avenue, Burnham made many friendships with Chicago’s elite. His ties to the city’s most wealthy and powerful citizens gave him an edge when the city vied for a most prestigious prize: Hosting a World’s Fair.

There has not been a World’s Fair in the United States since 1984. The last Fair, hosted in New Orleans, entered into bankruptcy before its six-month run ended. More than one generation of Americans has never attended, and perhaps never will attend, a World’s Fair. Remnants of 20th century Fairs, such as New York’s Unisphere and Seattle’s Space Needle, are camp icons. It is easy to forget that World’s Fairs were once huge, heavily attended spectacles, showcasing technological innovation and, if the backers were lucky, generating significant profits.

The first World’s Fairs were mainly industrial exhibitions. Between 1798 and 1851, Paris hosted eleven such shows. Other countries began to take notice. Always one to engage in one-upmanship with its rival nation, Great Britain decided to host its first exhibition on a scale that would dwarf anything France had thus far accomplished. Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, and Henry Cole organized the bombastically titled Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. The Great Exhibition, now recognized as the first World’s Fair, was housed in a fantastic mega-greenhouse that came to be known as the Crystal Palace. The 1851 London-based event helped to solidify awareness of Britain’s industrial and technological leadership. It was also hugely profitable: Its surplus of what would be more than $22 million in 2017 was used to build several museums, including the Victoria and Albert. There was even enough leftover money for a trust to fund industrial research grants. The trust is still in existence.

The London Great Exhibition’s Crystal Palace

The United States did not host a major exposition until 1876, when the Centennial Exposition opened in Philadelphia. Four years in the making, the event contained some 200 buildings and drew more than 10 million visitors. While it did not achieve a profit for its investors, the Centennial Exposition established the U.S. as a formidable source of manufactured goods. It ultimately enhanced the nation’s viability by helping to spur the growth of exports.

Stereopticon image of Memorial Hall, Centennial Exhibition, 1876.

Following the success of Philadelphia, it was time for another World’s Fair. This one would commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of the New World. Washington, D.C., St. Louis, New York and Chicago initially vied to host the exhibition. It soon became evident in the timeless “pay to play” scheme of things that only New York and Chicago possessed the necessary financial muscle to host an event of such magnitude. Although Chicago was only some 20 years beyond the 1871 fire that devastated the city, its resurrection was rapid and spectacular. It was, defiant of any odds, a formidable contender. The eyes of the nation focused upon the two great cities: New York, America’s locus of power, longtime financial center, versus aggressive, new monied Chicago. The U.S. Congress would be the final decision-maker of the Exposition’s venue.

In New York’s corner stood deep-pocketed giants such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, J.P. Morgan and William W. Astor. In Chicago, however, a few Prairie Avenue neighbors were not about to back down: In an early display of refusal to concede to Second City status, Philip D. Armour and Marshall Field used their considerable wealth to put Chicago forward. Other major players included Gustavus Swift, Cyrus McCormick and Charles T. Yerkes. Chicagoans of every income level pledged whatever they could to ensure their town would be the next location of a World’s Fair. New York was still the predicted host until a last-minute funding surge of several million dollars orchestrated by Chicago financier Lyman Gage turned the tables. Congress decided: Chicago would host the 1893 Columbian Exhibition. And Daniel Burnham would have some very big plans to make.

To be continued.