Field, Armour and Pullman

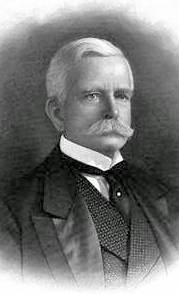

Marshall Field.

By Megan McKinney

The 1833 incorporation of the quiet village of Chicago as a town coincided roughly with the birth on the East Coast of three of the men who would power its growth into the great world city it would be by century’s end. George Mortimer Pullman was born in 1831, Philip Danforth Armour in 1832, and Marshall Field, in 1834.

Known as “The Trinity of Chicago Business,” Field, Armour and Pullman were three of the most prominent tycoons of the era and also each other’s most intimate friends—or at least as close as Field and Pullman were to having intimates. Marshall Field was the richest of the three, followed by Armour, and trailed by Pullman. The trio was instrumental in building the city and its amenities as well as setting a standard for taste and personal lifestyle.

Chicago, population 350, in 1833, when Philip Armour was a year old and George Pullman, two. Marshall Field would be born the following year.

Although the workaholic Armour rose at 5 every morning and was known for his determination to arrive at the office before his employees, there were days when he joined Field and Pullman and the three men walked to work together from their grand Prairie Avenue houses—carriages following in case of inclement weather.

Philip D. Armour.

They often met again for lunch at the “millionaires’ table” in the dining room of the Chicago Club, where they might return later to play poker.

George Pullman.

Aside from Pullman, Armour and his neighbors the Arthur Catons, the icy Marshall Field had no close friends. That Field would eventually make a widowed Mrs. Caton—the delectable Delia—his second wife is a story previously well told in Classic Chicago by columnist Melissa Ehret.

Marshall Field.

This series will eventually morph into George Pullman’s story; however there is an important aside regarding Marshall Field: His Eyes.

If eyes are indeed a window into the soul, knowledge of the eyes of Marshall Field, his most striking feature, is essential. Variously described as steel gray or bright blue, they were eyes that could shatter the composure of the most self-assured men. His nephew Stanley Field recalled that he “had the coldest eyes you ever saw and they read you through and through.” Writer Wayne Andrews commented, “At work he had only to lift his eyes from his desk for chills to run down the spines of brave men.” And the intrepid railroad magnate James J. Hill admitted that he found himself trembling inwardly during visits to Field’s office, adding, “He has the damnedest eyes.”

Although one contemporary described Marshall Field as “cold-souled and courtly” and another called him “a cool gray man,” he commanded universal respect and admiration. He was without a sense of humor and spoke very little, but he was affable enough social company and one of the city’s most desired dinner partners. Yet, when Field was with George Pullman, he became vivified. In fact, only with Pullman, Mrs. Caton and his rarely seen grandchildren did he truly come to life.

By the 1880’s, Field had become Chicago’s most powerful citizen; if he put his money and prestige behind something, it happened. In addition to Pullman’s Palace Car Company, he aided in the founding of Byron Laflin Smith’s Northern Trust and Samuel Insull’s Commonwealth Edison. Among the companies in which he was a major stockholder were U.S. Steel and the Chicago City Railway Company, and he lent Joseph Medill funds to gain control of the Chicago Tribune.

Marshall Field’s Prairie Avenue house.

Suspend disbelief for the present and imagine Marshall Field in his dining room on an early morning 14 decades ago:

The house at 1905 Prairie Ave. is silent, 25 rooms of poignant silence. Nannie Field is away, wandering the Continent—currently in Paris or perhaps the French Riviera—and both children have married and moved to estates in the English countryside. The servants are there but make no sound.

Field lifts the napkin from his lap, touches it briefly to the edge of his mustache, and rises from the breakfast table to walk along an elaborate hallway toward his library. He is a handsome man, reserved and formal, with weathered skin and the glacial gray-blue eyes; his hair and mustache had turned prematurely gray some years before. His carriage is erect, making his slender five-foot nine-inch body seem taller than it is, and today he wears a three-piece hand-tailored suit in a muted gray glen plaid. Below the high stiff collar of his white shirt a carefully knotted tie is secured with a single pearl tack. As always, his appearance is impeccable and his movements dignified and measured. Fellow Chicago Club member Edward Tyler Blair once commented that, in Europe, Marshall Field would pass for a nobleman or a diplomat rather than a businessman.

Hallway of Marshall Field’s Prairie Avenue house.

He walks along the hallway between embossed leather walls and beneath a 15-foot-high frescoed ceiling. The passage is lined with massive pieces of furniture and at its end a grand stairway curves elegantly upward. His selection of Richard Morris Hunt as architect was in the belief that a design by the Vermont native would reflect the Yankee virtues of “dignity, simplicity and common sense.” But Field himself had shown little Yankee restraint regarding the house. It was one of the first in Chicago to be wired for electric lights, and the Renaissance antiques he imported to furnish it were genuine—a startling innovation for that city. Previously its wealthy citizens had bought reproductions, but Field changed all that, revolutionizing their style in this as he had in so many areas.

He opens one of the double oak doors leading into the library to look for a small photograph he had promised to show to George Pullman. At one end of the room, marble pillars flank both an ornate fireplace and the priceless stained glass window above it. Low bookcases lining the room are fronted with glass doors and topped by marble busts, porcelain vases and other costly decorative objects. He immediately finds the picture, slips it into his pocket, walking back to the hallway and toward the door where his butler stands. Pulling on a pair of white gloves, he takes the hat handed to him.

Outside George Pullman is stepping down from his carriage.

You have just read the first segment of a 10-part Classic Chicago Dynasty series, which in Segment Three will morph into The George Pullman Story. The series will continue next with the daily walk of the two founders from Prairie Avenue to the Pullman Building in a segment titled The Trinity Founds Prairie Avenue.

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl