Prairie Avenue, 1887. Marshall Field’s stately home is in the foreground.

By Megan McKinney

Following the Fire of 1871, sleeping car tycoon George Pullman and meatpacking magnate Philip Armour united with Marshall Field in building mansions on Prairie Avenue. The city’s other barons of commerce and industry soon followed. Thus, throughout its 1880s heyday—before Potter Palmer completed creating the enduringly fashionable North Side—the six-block stretch from 16th to 22nd Streets was the center of affluent Chicago.

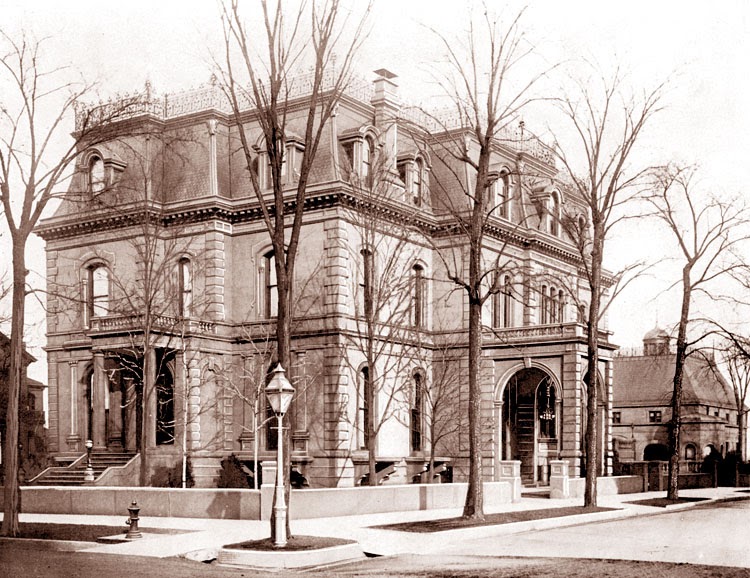

Prairie Avenue, 1890.

Joining Marshall Field in his grand house soon as the second Mrs. Field was the widowed Delia Caton. No further need for the rumored tunnel between their back-to-back houses.

This gloomy shot is of the Philip Armour residence. We will later come to the Pullman mansion, Prairie Avenue’s grandest.

Suspend disbelief for a time while we join Marshall Field and George Pullman as they begin their morning walk together, north toward their offices on the posh avenue they founded. It is spring, with a balmy late April breeze drifting gently off the lake. Above us, bright green leaves have begun to emerge from the arcing branches of elm trees, and the air is fragrant with the aroma of flowering bushes in neighboring gardens.

We are surrounded by Prairie Avenue’s elaborate mansions with their mansard roofs or pointed towers, great bay windows and porte-cochères. Their interiors feature bulbous conservatories, formal drawing rooms and third floor ballrooms. Across from Field’s house we pass the side-by-side houses of millinery wholesaler Edson Keith and his brother Elbridge.

Elbridge Keith’s house is center, with a portion of the Edson Keith house at right.

Chatting amiably, Marshall and George continue along the sidewalk, passing the red brick mansion of Chicago Title and Trust founder Fernando Jones. It will be only a matter of the weeks until the small honey locust tree in front of Jones’ white stone portico bursts into a cloud of snowy blossoms signaling the arrival of the reluctant Chicago spring.

The house of Fernando Jones.

Both men turn as horses drawing a carriage trot by, and they wave cordially to its passenger, Union Stock Yards founderJohn Sherman, whose daughter has married architect Daniel Burnham.

While architects Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root were working on the design for this house for John Sherman, Burnham and Margaret Sherman met, fell in love and married.

Aha! now we are coming to Pullman’s own three-story greystone, the grandest house on Prairie Avenue, surrounded by its own private park.

The grandest Prairie Avenue residence of them all: the George Pullman mansion at number 1729.

It seemed that every occasion celebrated by the Pullmans warranted an addition, such as that above, to the immense mansion.

Just north of Pullman’s elegant villa was the home of lumber baron Turlington W. Harvey.

The round-faced, chin-whiskered Pullman was a distant, narcissistic man, with a manner so starchy that he never removed his jacket—not even in his office—no matter how torrid the pre-air conditioning summer day might become. But he was not distant with Field, and neither man was ever more relaxed than when they were together.

During their two-mile walk north to the Pullman Building at Michigan Avenue and Adams Street, conversation might range from business investments and civic affairs to upcoming social events.

As always, there is much for the two tycoons to discuss, including developments at the Pullman Palace Car Company in which Field is a principal stockholder. Business—his own and possible investment in others—is the great merchant’s consuming passion and virtually his only avocation. Behind the ice blue eyes and courteous façade is a mind of frigid steel. Every conversation—whether with a shipping clerk or a fellow mogul—is motivated by this single-minded obsession. Before making an investment, he consults with experts, as well as those who are seemingly not so expert. He observes all that is happening around him, and every national or world event holds significance for him. An example of the Field mind at work was his swift reaction to the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Custer’s Last Stand at Little Bighorn.

He saw immediately that the massacre of General Custer and his men would prompt the federal government to forever crush the Native American population. Anticipating the subsequent westward rush of settlers, he began preparing for an expanded market in woolens, cottons and linens. This meant establishing an office in the English mill city of Manchester, and, when events happened exactly as he had forecast, Field’s wholesale division, and only his, was prepared for an explosion of the Western dry goods market.

The Pullman Building was across from where today’s Art Institute of Chicago stands.

When they reach Pullman’s imposing building, the two tycoons enter and walk directly into his spacious personal office as they often do after their morning walk. The rich mahogany, opulent carpeting and luxurious detailing in the room suggest Pullman’s Palace Cars. There is a fireplace against one wall, and a large mahogany desk in the middle of the room. Field sits opposite his host at the desk and chats for twenty minutes before leaving to continue north to his retail store at State and Washington.

As Field continues his walk from the Pullman Building to Marshall Field & Company on the lovely spring morning, it is within a complete world he enjoys with Pullman, Armour and the other late nineteenth century Chicago moguls—one in which their gracious tree-shaded residential street is only a short ride or a brisk walk from luxurious offices.

A glimpse into the world of George Pullman at 1729 Prairie Avenue.

In that era before federal income taxes, when servants were each paid approximately five dollars a week, households were fully staffed with a butler, second man, cook, laundress, multiple maids, a gardener or two, a coachman and groom, plus nurses and governesses. Butlers and coachmen were often English—or in the case of Pullman former slaves—but most of the servants were Irish immigrants and many became lifelong members of an extended family circle, continuing to live with their employers long after they were able to work. Behind the stately homes were coach houses that held broughams, victorias, phaetons and other handsome equipage for transporting their owners. Quartered nearby were carefully groomed horses and the requisite family cow.

It was indeed a complete and lovely life.

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl