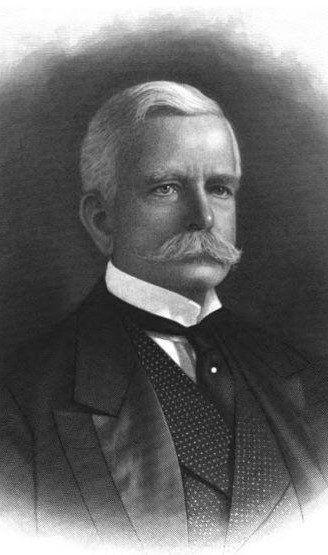

Marshall Field

By Megan McKinney

Silent, courteous, proper, and dignified. These were the adjectives contemporaries used in describing the first Marshall Field. You could add: measured, emotionally self-sufficient and inscrutable. He was discreetly elegant in hand-tailored suits with immaculate linen and no matter what the season he wore white gloves. But it was his eyes that were the most striking feature of his appearance. Variously described as steel gray or bright blue, they were eyes that could shatter the composure of the most self-assured men.

John D. Rockefeller.

Two of the most consistent characteristics of the inner man were a Yankee frugality and his sense of honor in commercial dealings; never at any time in his career did he engage in sharp business practices. John D. Rockefeller may have been the richest man in 19th century America, but Marshall Field paid the nation’s highest property taxes.

George Pullman.

Field’s personal manner was understated and markedly correct; he spoke very little in public and was reluctant to give interviews. Aside from George Pullman, Philip Armour and his neighbors the Arthur Catons, he had no close friends. His only amusement was playing low stakes poker in the evening at the Chicago Club, mainly for the rather stilted companionship it provided—although he did occasionally host Sunday morning breakfast gatherings in his Prairie Avenue dining room for a few male friends.

Philip D. Armour.

The Field family traces its roots past the Norman Conquest to the De la Felds of Colmar in the French region of Alsace and, more recently to Zachariah Field who arrived in Dorchester, Massachusetts in 1629. Although Marshall Field would become the richest and most influential man in late 19th century Chicago, he was born in 1834 the son of a hill farmer and his wife outside Conway, Massachusetts.

By working in a Pittsfield, Massachusetts dry goods establishment as a young man, he proved that he was a gifted retailer and, at the suggestion of his older brother, Joseph, he decided to leave Pittsfield in 1856 to venture out to the mushrooming economy of Chicago. Although his employer immediately offered him a partnership in the firm to stay, Field declined and was given excellent recommendations to present to retailers in the West.

Potter Palmer.

Much has been written of Field and the spectacular intertwining career development he shared with four other immensely successful merchants—the Farwell brothers, Potter Palmer and Levi Leiter—therefore, we won’t add to it here. However, he and Leiter owed their success to the others and benefited hugely from their association with them.

Levi Z. Leiter.

Although Field and Leiter were temperamentally and philosophically incompatible, they spent a decade and a half sharing ownership of Chicago’s finest dry goods emporium and an allied wholesale business of ever-growing magnitude. Also ever-growing was the partners’ disagreement about the importance of the retail arm. Leiter wanted to dispense with it; the real money, he maintained, was in wholesale. But Field insisted that without the prestige and glamour of the retail presence their stock would be perceived as being no different than that of other wholesalers. The antagonism became so great that Field decided to end his partnership with Leiter when it came up for annual renewal in January 1881. After surveying Field, Leiter & Co. staff to determine its loyalty, he gave Levi the choice of buying the Field interest or selling his own share, naming a temptingly low figure. The surprised Levi, realizing the figure was low and thinking he would be the partner to buy, agreed to it. However, almost immediately, he became aware that if Marshall left the company, their key executives would go with him and he would be left with a phantom operation. The following day, Leiter informed Field that he would sell and was forced to accept the figure they had agreed upon. Thus, for $2,700,000, the business became Marshall Field & Co.

A spectacular wholesale warehouse H.H. Richardson designed for Marshall Field was completed by 1887.

During the next decade, not only did Field step up his efforts as a wholesaler to stores throughout the nation, but he also took his own retail operation to dizzying heights. Potter Palmer had invented the Chicago shopping experience; hence the store that Field and Leiter bought from him was a highly developed, sophisticated enterprise. But, like Palmer, Marshall Field had a sure instinct for what women wanted and how to present it to them. He continued to perfect Palmer’s product, making Marshall Field & Co. the shopping destination of choice for upper and upper middle class women.

He provided fine merchandise in a beautiful setting and was successful in making Marshall Field & Co. a magnificent place to visit, a safe place, a place where a woman, who would never think of venturing into a restaurant or theater unescorted, could go alone.

Field added a tearoom within the store, and then restaurants. He provided lounges where women could rest, read or write letters using the courtesy stationery and writing instruments he supplied. Just as men went to the Chicago Club to meet friends, read newspapers and enjoy lunch, their wives could do the same at Field’s.

Their carriages brought them to the store sometimes several times a week, and whether they indulged in serious shopping, sport shopping, or merely window-shopping, they were always treated with dignity and courtesy by employees who were of the highest caliber. A key ingredient in the success of his business was that Marshall Field respected and encouraged talent. Young men who demonstrated ability were promoted and well compensated, and several of those he mentored became multimillionaires.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl

This segment of Megan McKinney’s Great Chicago Fortunes, The Richest Man in Chicago will be followed by Marshall Field, His World.