By Lee Shoquist

At the conclusion of each movie awards season, I promise myself it will be my last to invest in the outcomes the Oscars. Yet with each year that follows, like perpetual Groundhog Day (itself conspicuously timed directly before each year’s nominations) I find myself just as committed as always: “Whom will ‘they’ nominate? How could they have picked that? They better not snub so-and-so! Don’t they recognize quality?”

While Punxsutawney Phil promised six additional weeks of winter this year, the recent Oscar nominations mean six furious weeks of additional studio campaigning and voter courting for trophies across a gauntlet of splashy industry events, saturated media interviews and carefully crafted publicist’s narratives to support each nominee’s candidacy and drive a potential win. “The Oscars don’t matter; they are just publicity and popularity”—this an annual caution from a Los Angeles industry friend lest I get carried away with the notion that my personal favorites must triumph. And perhaps a publicity game is the smart way to look at it rather than an arbiter of movie art.

Yet for many of us who grew up on the glamour and pageantry of the Oscars in former decades—eras where great movies and stars could still command respect, stature, allure and wonder even from your small town living room television console, after 11pm on a school night—the Oscars remain a nostalgic touchstone, despite their diminishing cultural relevance in a modern era where once larger-than-life movie stars are no more, nominated films largely lack prestige and the notion of Hollywood grandeur has long since faded to black.

A sharp decline in viewership

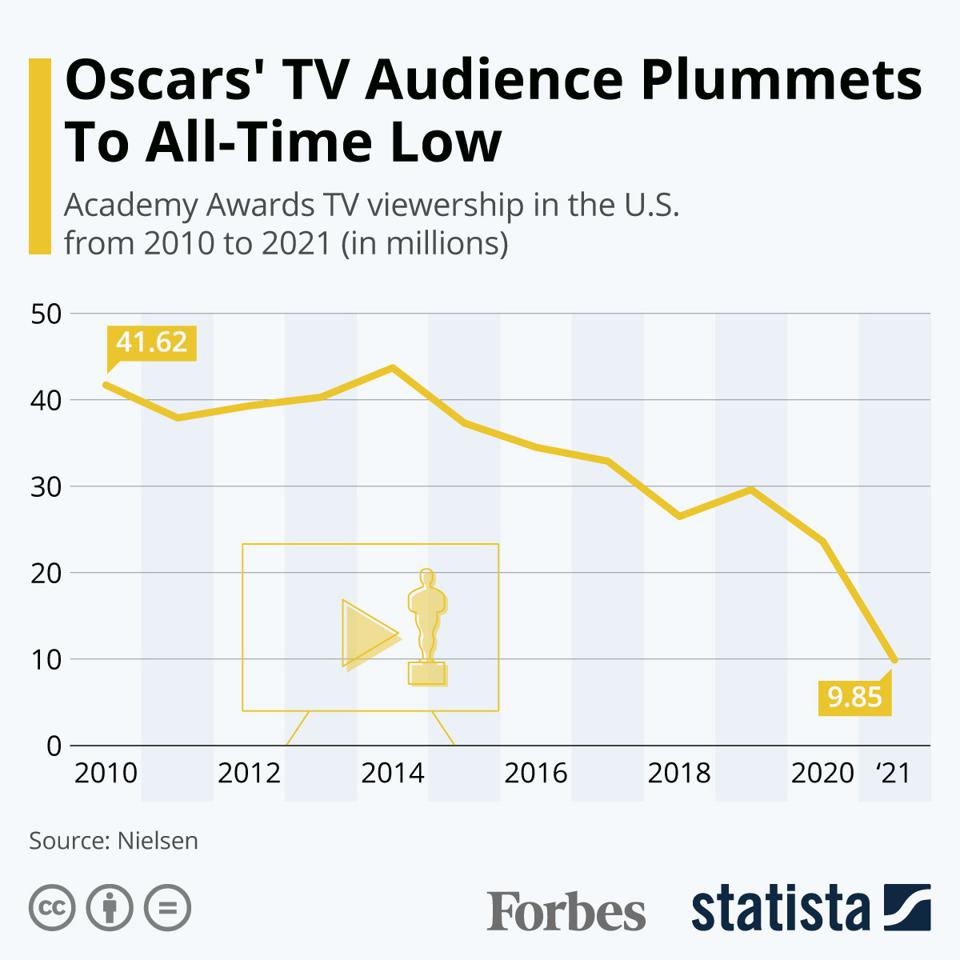

You may have heard that Oscar television ratings have plummeted since a high of nearly 56 million viewers in 1998, the year that a little picture named Titanic swept the awards. Remember Titanic—the international phenomenon and at-the-time biggest box office grosser ever that became a water-cooler conversation must-see, made Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet bona fide movie stars and gave us a sentimental Celine Dion tune still in endless (going on, and on, as she told us it would!) rotation decades later?

Flash forward twenty-five years and the Oscars are on now on life support, garnering a paltry 9.8 million viewers for Steven Soderberg’s pandemic-era 2021 soiree which, due to social distancing, substantially departed from Hollywood’s regal Dolby Theatre (the event’s longtime home, making but a glorified cameo) for the small-scale “charm” of Los Angeles’ Union Station, Zooming in assorted nominees and mustering all the aura of a regional sales recognition dinner held in the airport hotel convention center.

Why, exactly, are the Oscars no longer part of the cultural conversation for much of the populous? To begin with, the majority of nominated films are strictly art-house fare, and the winners are often derided as esoteric to commercial audiences. However great the movies may be, they have not exactly set the box office ablaze or captured the hearts and minds of the masses. Ironically, South Korea’s galvanizing Parasite, the 2020 winner embraced globally by critics, industry and audiences, became more of a worldwide conversation-starter than many recent American victors, including fine films like Nomadland, Green Book, The Shape of Water, Spotlight, Birdman, 12 Years a Slave, Argo, The Artist and The King’s Speech. While some of these films made substantial money and have their admirers, most courted specialized audiences and lacked traditional sweep.

Examining the last decade’s winners above, note the decided shift away from the commercial spirit and tone of post-2000 winners like No Country for Old Men, The Departed, Million Dollar Baby, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Chicago and Gladiator.

To take it a step further, consider earlier Best Picture winners like Forrest Gump, Braveheart, Schindler’s List, The Silence of the Lambs, Dances with Wolves, Platoon, The Deer Hunter, Rocky, The Godfather, Kramer vs. Kramer and Out of Africa. See a difference today? There has been a marked shift away from Oscars celebrating populist films that speak to everyone, everywhere and toward what one blogger recently suggested felt “like an indie film festival.”

Few quality commercial films

Why this trend? To begin with, Hollywood has abandoned making films like those mentioned above—commercial entertainments crafted by seasoned, often veteran directors and able to appeal to all viewer demographics. Many genres are now also off the table in commercial cinema (love stories, for example) leaving a few types of films to dominate the commercial arena: CGI fantasies, ever-profitable horror pictures, exceedingly broad comedies and buddy action pictures. Drama, it would seem, is also a casualty of what defines today’s entertainment. And while 2021 saw a welcome renaissance in movie musicals, their collectively weak box office will likely put a stop to any future outings without steadfast admirers or built-in audiences (like the upcoming movie adaptation of Wicked, for example).

Clearly today’s hackneyed commercial entertainments (The Woman in the Window and The Hitman’s Wife’s Bodyguard, I’m talking to you) signify creative bankruptcy in an industry largely sustained by escapist franchise movies in the superhero “multiverses” aimed at a very specific spectrum of viewership—males aged 13-35 (and while that age spread appears fairly broad, they seem to enjoy the same types of films)—that require little more than fan service construction (ahem, Black Widow). Even when an artist on the order of Nomadland Oscar-winner Chloe Zhao dips her toe into this sphere, her gifts are largely swallowed up and homogenized, as with the ambitious, disappointing Eternals, which attempted to tweak the formula with unsuccessful results.

Very few financial risks are taken today by studios, primarily driven by the airtight marketing logic of recreating past hits, hence the absence of original commercial fare. A quick look at most of what was produced in 2021 is hardly worth discussing, let alone awarding. If Hollywood no longer makes great commercial films that capture the public as those mentioned above once did, how can any be in Oscar contention? In an industry that seems to be actively choosing not to pursue the production of quality mainstream films, why shouldn’t the Oscars respond by turning toward smaller films of obvious integrity and artistry sorely lacking in their commercial counterparts? Consequently, while in decades past a “small” film might sneak in and win the Oscar, sometimes to great consternation—Ordinary People, Chariots of Fire—in the modern era such wins are increasingly the rule, not the exception.

Popular films ignored

Once in a while a film comes along that is both escapist fun but also has heart, technical prowess and captures nearly everyone who sees it. Quentin Tarantino’s successful Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which recently got close to Oscar, might certainly qualify. This year, the nearly $1 billion global grossing Spider-man: No Way Home achieved this feat, and its exclusion in the Oscars’ Best Picture lineup left many bewildered, including Jimmy Kimmel, who notably called out the Academy voters for including the labored, toothless satire Don’t Look Up while railing against Spidey’s omission.

Spider-man: No Way Home was not the only 2021 escapist picture that worked as terrific entertainment. Marvel Studio’s other big bet this year, the supremely witty and modestly scaled Shang-Chi: The Legend of the Ten Rings, worked beautifully on the star-was-born performance of newcomer Simu Liu and his snappy chemistry with sidekick Awkwafina, ratcheting the film up to a global gross of $432 million.

Another commercial hit, Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci, netted $155 million (and counting) in global ticket receipts but was sneered at by Academy members, who ignored the stars and the film, a meme-worthy cultural event built on the back of the singular Lady Gaga, credited for its international success as the only pandemic-era, adult-level film to make respectable box office.

Faring better with Oscar was Dune, the gargantuan, $165 million budgeted new adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 sci-fi classic, crossing $400 million box office worldwide and the recipient of ten Oscar nods including Best Picture. Though no one’s idea of an accessible crowd-pleaser, Dune’s often dazzling technical credits were too accomplished to overlook (though star Timothée Chalamet and director Denis Villeneuve were both sacked from contention).

Changing voter demographics

Considering the Academy’s recent and radically expanded membership increasing international, women and artists of color, the body is now at an all-time high of 9,362 members of different identities, backgrounds, interests and concerns, creating potential winners much different than those of past years.

Accusations of a lack of diverse representation in recent Academy nominees and a variety of ever-shifting cultural forces have also impacted voting habits, applying a lens of contemporary consciousness (“what is the movie or performance saying”) unseen in prior eras when the average voter demographic was the retired, white male over age sixty.

In past decades this voting block was able to wield influence, as we know from the notorious “whisper campaign” that tanked Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, a film that had won a record 25 international awards in the run up to the 2006 Oscars and was expected by everyone to take the top prize, particularly after Ang Lee had won Best Director moments earlier. When Jack Nicholson opened the Best Picture envelope and announced Crash as the surprise winner, the choice spoke to the influential power of the older, heterosexual white male voting contingent which included Ernest Borgnine, Tony Curtis and others on record as Brokeback Mountain detractors, all but coming out of retirement to lobby the rank-and-file voters into torpedoing the gay cowboy saga’s impending win. It worked.

A polarized culture

While the Academy voter demographic has shifted, so has the national mood. There is a growing sentiment that the current social and political polarization between liberals and conservatives has done the Oscars irreparable harm. While it may not be quantifiable by data, a substantial segment of the American population now admittedly “tunes out” to anything and everything coming out of Hollywood, believing it a haven of neo-liberal identity police and out-of-touch, ivory tower scolds, or worse, members of a secret cabal of child exploitation (yes, you read that right).

This is an unmistakable, post-Trump era turn exacerbated by a former president that demonized everything Hollywood (including, bizarrely, a Best Picture win by South Korea’s Parasite, inferring at a campaign rally that it was somehow unpatriotic to award our top movie prize to Bong Joon Ho’s beloved film). And after criticizing Trump on the Golden Globes, Meryl Streep found herself accused by the president of being “a Hillary lover” and “one of the most overrated actresses in Hollywood.” Never mind that she’s resided in Connecticut for the better part of forty years.

Such Trump warning shots at the “Hollywood elite” exacerbated the already fierce industry pushback on his policies, with stars taking every available public opportunity to criticize his administration, led by high-profile notables including Robert DeNiro, a vociferous critic who called Trump a “fake president” that he’d “like to punch in the face” and comedian Kathy Griffin, who was “cancelled” after an incendiary photo shoot luridly depicting the president’s decapitation. Bruce Springsteen also jumped into the fray with sustained protestations that Trump was a “threat to our democracy” and a “nightmare.”

Meanwhile, Spike Lee accused the president of being racist with “KKK-like tendencies,” even indicting him in the final sequence of his Oscar-nominated BlackKkKlansman. Sacha Baron Cohen piled on by making a lascivious buffoon out of an easy target, Rudy Giuliani, in Borat: Subsequent Moviefilm, causing Trump to retort that the satirist was “phony” and “a creep.”

This back-and-forth fanned flames of cultural discord and greatly contributed to an increasing conservative distaste for all things Hollywood (and liberal pushback against arch conservatives). And Hollywood, one could argue, is a contributor to the rift given that half of the moviegoing country is not interested in being hectored or lectured to that their beliefs are wrongheaded. The result of this squabbling? A recent Internet comment on an Indiewire news item found one conservative voice asserting that anyone who watched the Oscars—or even cared—was un-American. This is not a lone voice shouting in isolation.

No doubt such tensions are contributing factors for those who have permanently dialed off from the entertainment industry. But perhaps there is a simpler reason at hand. Just last week actor Seth Rogen ruminated that “…People just don’t care. I don’t care who wins the automobile awards. No other industry expects everyone to care about what awards they shower upon themselves. Maybe people just don’t care. Maybe they did for a while, and they stopped caring. And why should they?” Maybe Rogen has a point.

Absence of magic

Incendiary and opposing rhetoric aside, there may be another contributing factor to plummeting ratings, which is that the transporting mystique and glamour of the movies is over. There are certainly very few, if any, movie stars of the classic type today able to deliver on the fantasy of a larger-than-life, yesteryear “Hollywood.” Occasionally an actor punches through the marketing noise to remind us of what we’ve lost—and to my eye only one star did so in 2021 (we’ll get to that in a moment).

Today, the magic of once seeing a movie star on a 40-foot screen has been replaced by the intimacy of a smartphone, functioning as a window into stars’ 24/7 daily mundanities via Twitter and Instagram. How, exactly, can one cultivate a movie star persona when the ticket-buying public views hourly status updates that include Starbucks runs, navigating Los Angles traffic, scaling Runyon Canyon, or rummaging through antique shops in Sausalito? While the movie-watching experience has gotten smaller, so have the stars—both are now in our hands, and pockets.

Perhaps Gen Z and Millennial audiences, having not grown up on the star system, don’t care as much about the notion of movie stars anyway, at least not as much as they care about movie franchises, where the actors are often incidental to the marketing and the pictures will hit whether particular actors appear or not.

There is also data to suggest that given the rapid availability of content on their devices, younger generations are much less interested in watching live events (it isn’t just the Oscars that are dropping in viewership). Why sit for a 3-hour telecast when you can peruse clips of fashion, winners, or faux-pas almost immediately, on your device and at your leisure?

Should have been contenders

In truth, I have found little to be excited about in 2021’s nominees. There was certainly no equivalent across this year’s offerings to equal last year’s superb trinity of Nomadland, Promising Young Woman and Sound of Metal—great, provocative, richly observant films that will stand the test of time. Each of those films addressed the cultural zeitgeist—Nomadland and Sound of Metal spoke to the unexpected reinvention many of us underwent while life as we knew it suddenly became something quite different and challenging. And Promising Young Woman, a feminist battle cry, addressed “rape culture” and issues of consent in a post-MeToo climate. This year, only one film attempted to reflect where we have been, and that was Don’t Look Up, a celebrity parade of confirmation bias that was simply not insightful enough.

Still, we DO have a race underway, and not one without interest and surprises. Some contenders who had already crossed numerous hurdles and were expected to sprint to the finish line have been suddenly and unceremoniously benched for the season. Let’s consider a few such unfortunate surprises.

Lady Gaga, snubbed for what would have been her second Best Actress nomination, was electric in her dark-hearted House of Gucci star turn. If the national flower of Italy is a rose, she blossomed as a working-class Milanese “Elizabeth Taylor” in waiting with spirited ambition, whose social climbing and outsized Machiavellian manipulations revealed a ruthless Venus flytrap over the course of 2.5 absorbing hours. The smart trick of Ridley Scott’s measured film (a high drama sans camp, no matter what you may have heard) was that her “black widow” character was fascinatingly oblique. On the one hand, her Patrizia Reggiani was a world-class conniver scheming to dismantle a family and appropriate their empire; on the other, a spurned wife and proverbial strong woman behind a man lacking his own appetite for success. After her efforts propelled him into power, she was unceremoniously cast out of his kingdom. In truth, she likely deserved it.

But what Lady Gaga and Scott landed on here was a novel portrait of a smart, shrewd woman tossed out for a younger version when she was no longer wanted or useful. It would have been easy to make her a one-dimensional villain, but Lady Gaga delivered authentic, writ large emotions in the film’s final third. Despite her criminality, the movie asked us to also consider the callousness of her predicament.

The most decorated actress this season who hit every precursor nomination—Golden Globes, Critics Choice, Screen Actors Guild, BAFTA and won the New York Film Critics Circle Best Actress prize, Lady Gaga reminded us what a great movie star can do—theatrical yet natural and with presence to the max, conveying insecurity, impetuousness, romance, drive, deviousness and, finally, a taste for the diabolical. She was a villain, sure, but I was surprised how much I felt for her in the final shot.

Also overlooked for Best Director was Canadian filmmaker Denis Villenueve, an assured technical visionary who brings authority and scale to Hollywood outings that have included Blade Runner 2049, Arrival and Prisoners, and who meticulously adapted Dune to the tune of multiple Oscar nods but was ignored by the Academy in favor of surprise nominee Ryusuke Hamaguchi, the Japanese filmmaker behind the celebrated Drive My Car and Paul Thomas Anderson, who rode a late surge of voter affection for his lovingly mounted, pleasantly aimless and very enjoyable 70’s romance, Licorice Pizza. The degree of difficulty in directing Dune was onscreen in every frame of its spectacular world building (which unfortunately came at the expense of its dramatic urgency) and it is a safe bet that Villeneuve will be back in future contention when 2023’s Dune: Part II completes the saga (and perhaps his route to Oscar).

Irish actress Catriona Balfe, expected to get a Best Supporting Actress nod for her radiant Belfast portrait of a mother raising sons in a war zone, lost her chance to Dame Judi Dench for the same film. Opening her grandson’s heart to reveal a budding artist transported by movies and theater, Dench brought her usual humor and tenderness to a bittersweet, if minor, performance. After eight nominations and famously winning the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for an eight-minute turn as Shakespeare in Love’s Queen Elizabeth, it is clear that “they really, really like her”—but apparently at Balfe’s expense.

Ruth Negga, who gave one of the year’s best supporting performances in Rebecca Hall’s Passing, was nominated for Best Supporting Actress by the Screen Actors Guild and won the National Society of Film Critics award. Given such kudos, she was widely thought to be “in” for her performance as a Black woman passing for white, torn between two worlds, during the 1920’s Harlem Renaissance. In a vivacious and ultimately tragic turn, Negga, previously nominated for Best Actress in 2016 for her quietly powerful work in Loving, garnered across-the-board raves. What went wrong? Likely the surprise nomination of the very deserving Jessie Buckley for The Lost Daughter, a film that broke late and has remained firmly in “the conversation,” had something to do with it.

Two-time Oscar-winning Iranian master Asghar Farhadi (A Separation, The Salesman) is one of the few global filmmakers today, meaning he makes multilayered films that speak to modern day urban lives in Iran while simultaneously containing universal human truths accessible and absorbing regardless of culture. This year, Farhadi missed a Best International Feature Film nod for his superlative morality play A Hero, about a prisoner on a two-day freedom furlough desperately trying to extricate himself from the crushing debt keeping him incarcerated. Like all of Farhadi’s work, A Hero sits at the intersection of class, culture and family, this time offering a pointed social critique of what is known today as cancel culture, with soulful star Amir Jadidi ensnared in a no-good-deed-unpunished quagmire threatening his legal and reputational livelihoods. As always, Farhadi suggests no heroes or villains, but rather a myriad of balanced perspectives around fatherhood, good Samaritans, conscience and loyalty in the digital age.

Aaron Sorkin and Oscar are usually simpatico—indeed the famed writer/director won the Oscar for penning The Social Network and was nominated for his screenplays for Moneyball, Molly’s Game and The Trial of the Chicago 7. Yet despite his ambitious work in Being the Ricardos, which took a non-traditional approach to a Lucille Ball biopic in depicting a 1952 week in the production of I Love Lucy informed by a communist accusation, domestic strife and the backstage clashes of a creative genius battling studio brass to realize her vision, Sorkin was left off the nominations list. Perhaps his picture had two things against it, namely its perception as primarily an actors’ show and one functioning more as hagiography than biography. Sneaking into the Best Original Screenplay category instead was Norway’s celebrated The Worst Person in the World, which likely trumped Sorkin’s shot.

Without an editing nomination, it’s difficult—though not impossible—to win a Best Picture Oscar. Just ten times in Oscar history has a film without an editing nod taken the top prize, a short list that includes masterworks like The Godfather, Part II, It Happened One Night, Ordinary People and Annie Hall. Recently, Birdman also managed to snag the top prize without an editing nod, namely because its single shot novelty approach suggested virtually no edits across its two-hour running time. This year Belfast missed Best Editing, which could be a key harbinger come Oscar night.

Who is looking good for a win?

Looking toward potential winners amongst the films and performances that were nominated in top categories, the picture remains unclear for some in a year still heavily influenced by a pandemic that has shellshocked box office for adult-level movies, leaving many of the nominated films and performances challenged to reach broader audiences or amass much momentum or cultural cache. Yet despite our lack of clarity on who will get his, her or their hands on the coveted statues next month, we can still make a few predictions, or at least winnow down the nominees into likely frontrunners based on prior wins and nominations, gut-level intuition and individual contender narratives.

Best Picture

At this moment, Best Picture appears to be The Power of the Dog’s to lose. The Jane Campion-directed, psychological chamber piece set on the Montana range of 1926, has won more awards this season than any other film. Going into the Oscars, this substantial margin advantage suggests the picture might sweep wins across a lion’s share of its 12 nominations. Both the film and its director are deeply respected by a healthy contingent of voters. Yet the subject matter—a slow-burn character piece about repressed identity with a final reel coup de grace that upends our expectations—is not for everyone, and in some corners is regarded as polarizing.

Further complicating the picture’s path to victory is Oscar’s preferential ballot, on which voters rank their favorites. On the preferential ballot, multiple rounds of counting and redistribution ultimately push some films to the top while eliminating those at the ballot’s bottom. A film ranked high on the ballots—in the top few spots but not necessarily with the most number one votes on the first round of counting—have a better shot at being a winner. This produces a pick that is “most broadly liked” rather than feverishly supported. Potentially divisive films that inspire both passion and revulsion can find themselves in jeopardy by scoring on the top and bottom of the ballot, unable to garner enough broad support in the top slots to garner a win. It remains to be seen whether The Power of the Dog can perform well on a preferential ballot, but since the industry’s Producer’s Guild applies the same methodology, a win for the film there would suggest a viable path to Oscar.

The Power of the Dog is also a Netflix film, and to date there has been a notable industry bias preventing Oscar’s top award from going to a film either original to or distributed by, for example, Netflix or Amazon (though each has amassed scores of nominations and even acting wins). If that symbolic barrier falls this year and Netflix is awarded Hollywood’s top honor, it will be regarded as a victory belonging not merely to the film but also the streaming industry, and a perceived studio embrace of an alternative, non-box-office-driven business model that Hollywood has so far refused to acknowledge as the industry’s future, most notably by Steven Spielberg’s 2018 remarks that films from streaming platforms should only be eligible to receive Emmys.

Best Director

As close to a sure thing as we have this season, Best Director contender Jane Campion, perhaps considered the greatest living female filmmaker and who won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for her lauded 1994 The Piano, will likely capture the trophy for her sterling directing of The Power of the Dog. With a Golden Globe and mantle full of critics’ prizes this season, the opportunity for the Academy to award one of the foremost film artists in the world will prove irresistible, marking two consecutive years a woman will have won Best Director.

Best Actor

In Best Actor, we have a mano-a-mano shaping up between a populist performance by a never better Will Smith as the indefatigable Richard Williams, father of Venus and Serena in King Richard, and Benedict Cumberbatch, the actor’s actor who burrowed deep into the toxic and ultimately moving heart of The Power of the Dog’s revisionist cowboy Phil Burbank, fraught with secrets, rage and repression. Considering Smith and Cumberbatch in a potential face off, we might look to last year’s shocking upset that found voters eschewing sentiment to award The Father’s Anthony Hopkins over the late, heavily favored Chadwick Boseman for his final turn in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. While Golden Globe winner Smith is currently the odds-on favorite, will Oscar take a similar route this year in awarding Cumberbatch’s method performance over Smith’s career high?

Best Actress

Since January’s Golden Globes, where Nicole Kidman upended Spencer’s thought-to-be-frontrunner Kristen Stewart, Kidman seems to have the wind at her back. To begin with, Being the Ricardos, while no one’s idea of a masterpiece, is a glossy actors’ vehicle featuring juicy roles for both Kidman and co-star Javier Bardem as Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Jr. In a dual performance as creative dynamo Lucille Ball and her TV persona, Lucy Ricardo—two very different incarnations onscreen and backstage—Kidman nailed Ball’s voices and manner, shutting down cynical Internet naysayers.

At the same time, Jessica Chastain is impossible to deny in perhaps a more transformative turn as former televangelist Tammy Faye Bakker in The Eyes of Tammy Faye, a film few saw but which Chastain elevated with a performance spanning more than thirty years from youthful optimism to downward pathos, giving us a reappraisal of a woman most often written off as a public joke. The decision may come down to which real-life woman voters wish to reward—Ball or Bakker? While four-time nominee Chastain gives the most indelible performance, which character do you think roughly 9,500 industry voters will embrace? This Ball appears in Kidman’s court, at least until the upcoming Screen Actors Guild Awards offer a clearer picture. My choice? I would have selected snubbed Lady Gaga, who may still win the BAFTA, where Kidman, Chastain, Stewart and The Lost Daughter’s Olivia Colman all failed to land nominations.

Best Supporting Actor

This year’s Best Supporting Actor trophy would seem to be Kodi Smit-McPhee’s for the taking. As The Power of the Dog’s mysterious son Peter, the offbeat young actor has won numerous critics’ prizes and a Golden Globe for a performance of near clinical detachment and, eventually, disturbing pathology. It is a tricky turn and like much of the film, about withholding and reserve; Smit-McPhee requires us to lean in and make our own conclusions about the motivations and culpability of his darkly unique character. At this time, there are no threats to Smit-McPhee’s trajectory.

Best Supporting Actress

In Best Supporting Actress, Ariana DeBose, as a fiery Anita in Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story, has a clear path to victory after winning numerous critics’ prizes and a Golden Globe. With arguably the year’s biggest shoes to fill, DeBose followed legendary Rita Moreno (who captured the Oscar for the same role in Robert Wise’s 1961 original film version) by receiving a new round of universal huzzahs for her musicality, dance and dramatic chops. Chief competition comes from the great Aunjanue Ellis as King Richard’s Brandi Williams, who opposite co-star Will Smith has a powerful late picture showdown covering vast personal and parental ground. While Ellis has the big, heavy lifting Oscar scene, DeBose has the “it” girl factor and undeniable charisma.

Best International Feature Film

In Best International Feature Film, current winds favor Japan’s celebrated Cannes winner Drive My Car, the recipient of four Oscar nods this year including Best Picture and Best Director for filmmaker Ryusuke Hamaguchi. The story of an unlikely bond that grows between a renowned actor suffering the loss of his wife while directing a Hiroshima production of Uncle Vanya, and the younger, female driver assigned as his chauffer, Drive My Car is a restrained, three-hour examination of grief, loss and unlikely rebirth.

But there is a very public and growing industry enthusiasm for Norway’s revelatory The Worst Person in the World, the affecting story of a young woman’s search for herself through a number of relationships, jobs and encounters, featuring BAFTA-nominated star Renate Reinsve in a most original performance. It is a sparkling film, at once a romantic comedy and poignant drama with something to say about the modern, youthful identity.

As evidenced here, while some categories seem to have emerging frontrunners there are an equal number still undecided, which for many contenders is not a bad place to be entering into the final campaign rush. As Lauren Bacall memorably considered in her 2005 autobiography By Myself and Then Some, frontrunner status throughout Oscar season can ultimately turn out to be a curse. Reflecting on her heavily predicted Best Supporting Actress win for Barbra Streisand’s The Mirror Has Two Faces, which turned into a shocking loss to The English Patient’s Juliette Binoche, Bacall observed, “It’s not a good thing to be a shoo-in.” Such eleventh-hour reversals of fortune are common enough that any of the proposed victors above might go home empty-handed.

In the less-than-infallible art of prognosticating movie awards—a fool’s errand of parsing historical stats, factoring key precursor nominations and reading tea leaves amidst ever-shifting (and often fickle) industry sentiments—if you care too much, “the world will break your heart ten ways to Sunday.” That line, a personal favorite from a recent Oscar contender, is one I’ve considered time and again in my efforts to practice detachment from the outcomes of the Oscar race.

It hasn’t worked. I’ve tried.