BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

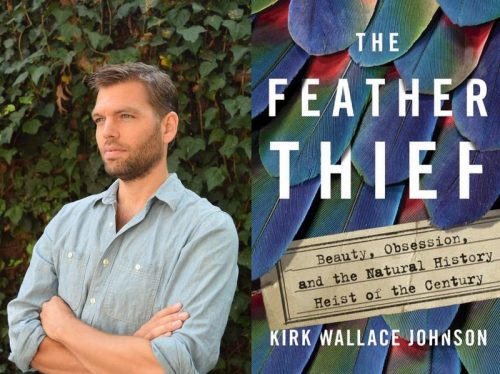

The international heist most talked about this year isn’t gold or a rare masterpiece (or Sandra Bullock’s team effort in Ocean’s 8), but that of 300 of the rarest and most dazzling of bird skins, each almost 200 years old. Former Chicagoan Kirk Johnson’s bestseller, The Feather Thief, solves what has been called the “natural history heist of the century,” pulled off by a 20-year-old American flutist with a passion for salmon fishing.

The Feather Thief.

Kirk, a 2002 graduate of the University of Chicago, served in Fallujah, Iraq, as regional coordinator for the US Agency for International Development and had subsequently formed the List Project to aid Iraqi refugees who had previously worked for the United States government there. For Kirk, a “zen fly fishing experience” on the Rio Grande River in New Mexico would relieve some of the stress and frustration of his commitment to the refugees he so wanted to help in Iraq. He himself had suffered a near-death experience while in Iraq as well as post-traumatic stress: “For fly fishers, all that matters is the temperature of the water, the speed of its flow, the skittishness of the fish, the accuracy of the fly, and the neatness of the catch. It is so pure, so untouched, so hopeful.”

Kirk Wallace Johnson. Photo by Marie-Josee Cantin Johnson.

A fellow angler told Kirk about Edwin Rist, the obsessive musician who in 2009 broke into the British National History Museum in Tring, with one of the largest collectors of exotic birds, who stuffed rare quetzals, blue birds of paradise, flame bowerbirds, and many others into a suitcase in the dead of night and disappeared.

The British Natural History Museum in Tring (Photo credit: Gerald Massey).

Edwin Rist, 2010 (Image copyright: PA IMAGES).

The theft had instant international impact. The birds, several of which had become extinct, were considered archival relics from a lost era. The crime was regarded not only as pilfering from dusty drawers in a museum basement but stealing knowledge from humanity.

As feathers from the birds made it onto coded web sites and lured fly-tiers to spend huge amounts of money, Kirk was hot on the trail:

“I found it so bizarre as to be captivating—quirky and obsessive individuals, strange birds in curio cabinets, archaic fly recipes. It was a welcoming diversion from the unrelenting pressure of my work with the refugees.

“It struck me as impossible to hear about a museum heist of dead birds carried out by a student flautist to meet the insatiable demand of salmon fly-tiers and not want to learn more. This side hobby turned into a mission. I realized that the loss it represented turned into a loss in scientific understanding.”

Kirk would travel the world in his search to learn more, led to Amsterdam where he meet with Edwin Rist, who has escaped being sentenced to prison because of a diagnosis of Asperger’s Syndrome.

The son of State Representative Thomas L. Johnson and Virginia Johnson, a policy adviser to the Illinois Attorney General, Kirk has traveled internationally from a young age. He began studying Arabic after a visit to Egypt with his grandmother, skipping his high school graduation to study at the Arabic Language Institute at the American University in Cairo.

We spoke with Kirk about The Feather Thief and The List Project.

You grew up in West Chicago and lived there as a child. Did you read a lot growing up? Did you think that being a writer was in your future?

I read quite a bit, but I was also the youngest of three boys that grew up on something resembling a suburban farm, so I was constantly chasing after them outdoors. When my oldest brother got a computer (this is the mid-eighties), all I wanted to do was play King’s Quest, but he set up ground rules: for every hour I wanted to play, I’d have to read a book of his choice for an hour, and write out every word I didn’t know, along with its definition. As a seven-year-old, it was a drag, but I still smile whenever I encounter one of those words, thirty years later.

How does the saving of these birds relate to the importance of preservation? What underlies relationships and lasting things like loyalty and history?

When I first heard about the heist of these birds, I had no idea that museums maintained such vast collections. I naively thought that what we saw in the public display cases constituted the bulk of each museum’s collection. But what the feather thief’s heist revealed was a centuries-old chain of curators who protected millions of natural history specimens out of a beautiful belief that they might one day provide answers to questions that scientists hadn’t yet thought to pose.

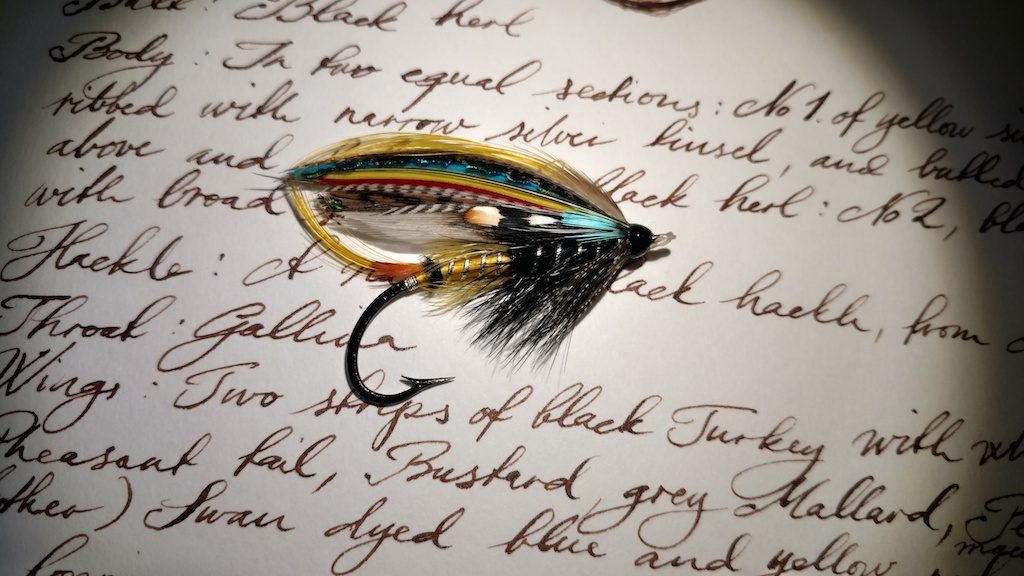

The Jock Scott fly, tied by Spencer Seim, the fly-fishing guide in northern New Mexico that first told the author about the Tring Heist. Instead of using costly feathers from exotic species, Seim uses substitute feathers, made from dyeing plumes from ordinary game birds like turkeys and pheasants (Photo credit: Spencer Seim, Ziafly.com).

Each generation interrogates the same specimens with new technologies and new theories, and the bird skins have yielded insight after insight. The collections of The Field Museum in a study out of the University of Chicago played an important role, using 135 years’ worth of specimens to demonstrate how societal dependence on coal impacted the environment.

Most of all, I would like your advice to people on how they can go about working to the place where they are doing something they really feel called to do, particularly when that is helping others.

I often feel unqualified to answer questions like this because the last two projects of mine were, to differing degrees, not deliberate choices or the result of some strategy. I didn’t plan on becoming a refugee advocate. I saw something rotten happen and wrote about it, which then thrust me into a position where I felt I had do something about it.

I certainly never thought I’d write a book about a feather thief. I’d become obsessed with fly-fishing as a form of escapism from the daily demands of the List Project and heard about the museum heist from a random fly-fishing guide I’d hired one day. I don’t know if I would’ve written a book about it if I hadn’t learned about the immense scientific value of the specimens, that so many were still unaccounted for, and that justice ultimately been denied in this case.

I feel as though I only achieved a tiny fraction of what I’d hoped to in both cases (our doors are as closed as they’ve ever been to Iraqis and Afghans that risked their lives for us, and too many of those birds are still missing), so I cringe at the idea of giving any advice, but to the extent that it’s useful, I’m always amazed (and frustrated) at just how long it takes to effect change, and how fragile those gains often are.

I used to think that the Statue of Liberty and what it represented was as central to American identity as apple pie, but it turns out that long-held values like these can be shredded in a couple years. Like many, I tend to want quick solutions to complicated problems, but our institutions of governance can’t and won’t provide those. So whatever someone’s calling might be, my only inconsequential bit of advice is to ration your energy for the long haul: it’s possible and essential to provoke change but keep your patience and fight like hell to protect your gains.

You write about the zen of fly fishing. What would you say about the experience?

I would say that people who get out and try it will find out very quickly whether it works for them. For me, it was almost an instantaneous sensation that I would spend the rest of my life doing it. I’m just as wired and burned-out by screens as anyone, so to be able to go somewhere where there are no cell signals and rely upon my ability to be quiet, to move deliberately, and to patiently focus on details happening on or around the river is profoundly antidotal. I’m routinely surprised that the sun is already setting: seven or eight hours on a river feel like 45 minutes to me.

Have many fly-fishing devotees been in touch with you after reading the book?

Quite a few—the book has gone far and wide in the fishing community. The overwhelming majority of anglers have been supportive and have, for the most part, regarded the art form of tying Victorian salmon flies as an quirky outpost. I think that the book confirmed a lot of their perceptions about just what goes on in that subculture. But there have been numerous emails from salmon fly-tiers who have read the book and wanted to share more leads about the fate of the missing skins.

The targeted species (Photo courtesy of the Natural History Museum, London).

Are you still fly-fishing?

I’m still fly-fishing but not nearly as much as I used to—we have a two-year-old son and a one-year-old daughter, and we live in Los Angeles, which isn’t exactly a mecca for angling. I have climbed over the barriers walling off the LA River, though, and fly-fished for carp, which is new terrain for me.

What are you doing right now in your work to save our Iraqi allies? What do you want our readers to know about the project?

I still write and speak about their plight, occasionally, and regularly assist on asylum cases by offering up affidavits. I recently played a small part in helping an Iraqi woman who was shot in the head while working for a major defense contractor seek redress through the Defense Base Act. She lost her sight and sense of smell and had to flee the country, but she was entitled to some compensation for her injuries.

How do you relate your writing with the List Project? I have such a strong sense of your devotion to what is worth saving.

I’m not sure the List Project would’ve happened without writing. I had no plans to launch a non-profit—it wasn’t until I wrote an op-ed (it was my first, so I didn’t really know what I was doing) about the Iraqi refugee crisis that my inbox became inundated with desperate appeals for help from Iraqis that had risked their lives to help us during the war. The more I wrote about their plight, the more my obligation to try to do something about it grew.

***

Kirk, who has written frequently for The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and other publications, has a new writing project in the works that his readers, including myself, are greatly anticipating.