May 1, 1893: It was good to be king. Or, in this case, it was good to be Daniel Burnham, who chaired the Board of Architects. On this day, a not remotely little plan he conceived three years prior was about to become electrifyingly real. He and a few of his Prairie Avenue neighbors, Marshall Field, George Pullman and Philip D. Armour, had organized the world’s biggest block party: The Columbian Exposition. Of course, the friends had to pass the hat to get a little startup money. By the time Chicago had prevailed over New York, Washington, D.C. and St. Louis, the Prairie Avenue luminaries and their contemporaries had raised $10 million to host the Exposition in their back yard.

By May 1, the costs had exceeded $28 million. Burnham’s treasured business partner, John Wellborn Root, had suddenly died early in the planning stages. Famed landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted transformed some 600 acres of ungainly, swampy grounds in Jackson Park into a fairyland, complete with stately promenades and graceful waterways. A magical Beaux-Arts city of elaborate buildings clad in snow-white stucco slowly rose from the imaginations of Burnham and his team of the world’s most distinguished architects. Standing in stark contrast to the poorest neighborhoods of Chicago that had not fully recovered from the 1871 fire, the White City, as it came to be known, would captivate the millions who passed through it. By the time construction was complete, the 14 principal structures contained 63 million square feet of floor space.

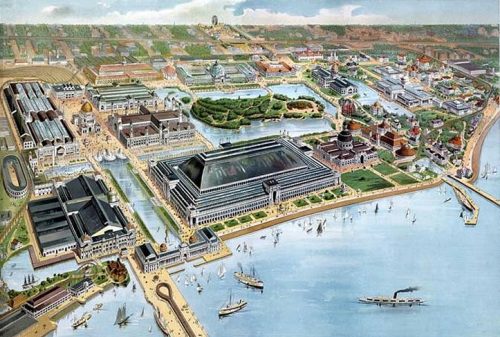

Aerial view of the 1893 Columbian Exposition

On May 1, Opening Day, President Grover Cleveland arrived to do the honors with Mayor Carter Harrison before more than 100,000 spectators. He flipped a lever, thus awakening the dynamos that would power the spectacle. Some 120,000 light bulbs began to glow. The Fair literally burst into a most luminous life.

All aglow: The World’s Fair at night.

During the six months of the Fair’s existence, some 27 million people came to visit. That translates to roughly 25% of the U.S. population at the time. This is an amazing statistic given the relative scarcity of transportation and the nation’s predominantly agrarian culture. But come they did: on the New York Central, the Michigan Central, and the Santa Fe. They arrived on horseback, by coach. Most stayed for a few days, marveled at the exhibits, discovered Juicy Fruit gum, gobbled the new dessert treat, “brownies,” purchased souvenirs and went home.

Some visitors came from far away. Chicago considered itself honored to host dignitaries from all over the globe. One of the most prominent groups affiliated with the Columbian Exposition was the Board of Lady Managers, one of the earliest female organizations officially recognized by the U.S. Congress. Chairing the Board was Bertha Palmer, half of one of Chicago’s first Power Couples. A well-educated lady of the South, she proved to be a brilliant match for department store and hotel magnate Potter Palmer. She was revered in her own town, but her star was just beginning to shine on a worldwide basis. And so it came to be that she received not just ingratitude but insults from one of her prized guests at the Fair.

Chicago society was clearly flexing its collective muscle when it secured one Maria Eulalia Francisca de Asis Margarita Roberta Isabel Francisca de Paula Cristina Maria de la Piedad, otherwise known as the Infanta Eulalia of Spain, as a visitor. What better way to commemorate the good judgment of Queen Isabella to send Columbus on a voyage than to have a present-day representative of the Spanish crown show up at your block party?

Feeling the joy: The Infanta Eulalia.

The “Innkeeper’s Wife.”

The denizens of Prairie Avenue and Chicago’s other elite enclaves went beyond their already lavish entertainment machinations to wow the Spanish royal. However, the Infanta was famously not impressed with the Windy City’s luminaries. While Chicagoans were accustomed to snubs, they did not take kindly to Eulalia’s catty reference to Mrs. Palmer as a “lowly innkeeper’s wife.” While the Infanta would write socially insightful books later in life, she was not at her best in 1893. Bertha Palmer was too graceful at the time to have publicly commented upon the Infanta’s having married her first cousin, a union that would have inspired present-day critics with whoops of infantile glee.

Mrs. Palmer would exact revenge when on a visit to Paris some years later, she was invited to a reception for the Eulalia. According to Stephen Longstreet’s wickedly funny book, Chicago, Mrs. Palmer declined to attend, reportedly saying, “I cannot meet this bibulous representative of a degenerate monarchy.”

Speaking of degeneracy, another element of the Fair piqued the ire of Mrs. Palmer even more than the haughty Spaniard: The Streets of Cairo. This most successful exhibit on the Midway featured Javanese women capable of never-before seen abdominal gyrations. In other words, belly dancers made their wiggly debut in Chicago, delighting millions of Fair attendees. Mrs. Palmer was infuriated, but the concession was wildly popular.

Beyond the dreamlike ambience of the White City, even beyond the views from the new Ferris Wheel, was a killer who would thrive in the crowds and prey upon young female visitors. The best way to learn about the dark side of the gleaming Fair is to read Erik Larson’s Devil in the White City. Rumored to be a future Martin Scorsese film starring Leonardo DiCaprio, its protagonist is, for obvious reasons, Daniel Burnham. Until the publication of Devil, few knew much about the antagonist, H.H. Holmes. A New Hampshire ne’er do well who came to Chicago to pursue a career in dubious medicine, Holmes bought himself a building in Englewood, near the fairgrounds. He dubbed the structure “The World’s Fair Hotel.” Holmes operated a pharmacy on the ground floor, but the upstairs rooms contained architectural features that would have astounded even Burnham. Holmes configured the rooms to incorporate secret passages, tiny spaces, and a chute that would swoop dead bodies to the basement with its conveniently installed kiln.

The “Devil,” H. H. Holmes

Holmes’ World’s Fair Hotel

Holmes appeared to be a reasonably good-looking man, so much so that he was engaged to at least two women. He tortured and slaughtered countless more. Thanks to the kiln, it was easy to dispose of them. In addition to having committed murder, Holmes engaged in insurance fraud. While involved in the latter malfeasance, he was arrested in Philadelphia. Detective Frank Geyer, while investigating Holme’s financial crimes, dug a bit deeper into Holmes’ past. Geyer was horrified to discover that the imprisoned Holmes was also a mass murderer. Some estimates place the number of Holmes’ victims at 200. The odious Holmes was hanged on May 7, 1896 in Philadelphia’s Moyamensing Prison.

By the time the Fair ended on October 31, 1893, Mayor Carter Harrison was assassinated by a would-be seeker of office. A smallpox epidemic swept through Chicago. And, shortly after the visitors had gone home, the Ferris Wheel and midway disassembled, the last remnants of popcorn swept off the streets, the Fair caught fire. Many of the main buildings were destroyed. Only one of the glorious structures still stands: The Palace of Fine Arts, although today it is known as the Museum of Science and Industry. The only building constructed with every known method of fireproofing, to protect precious works of art, withstood the flames of 1893. When Chicago played host to the World’s Fair in 1933, the Museum had been reclad in Indiana limestone. This imposing yet beloved structure will serve as long as time permits as a reminder of the long-gone White City.