By Cheryl Anderson

“I like doing things, I hate possessing them. Memories cling to things and objects, so it is best to start all over again.”

– Eileen Gray

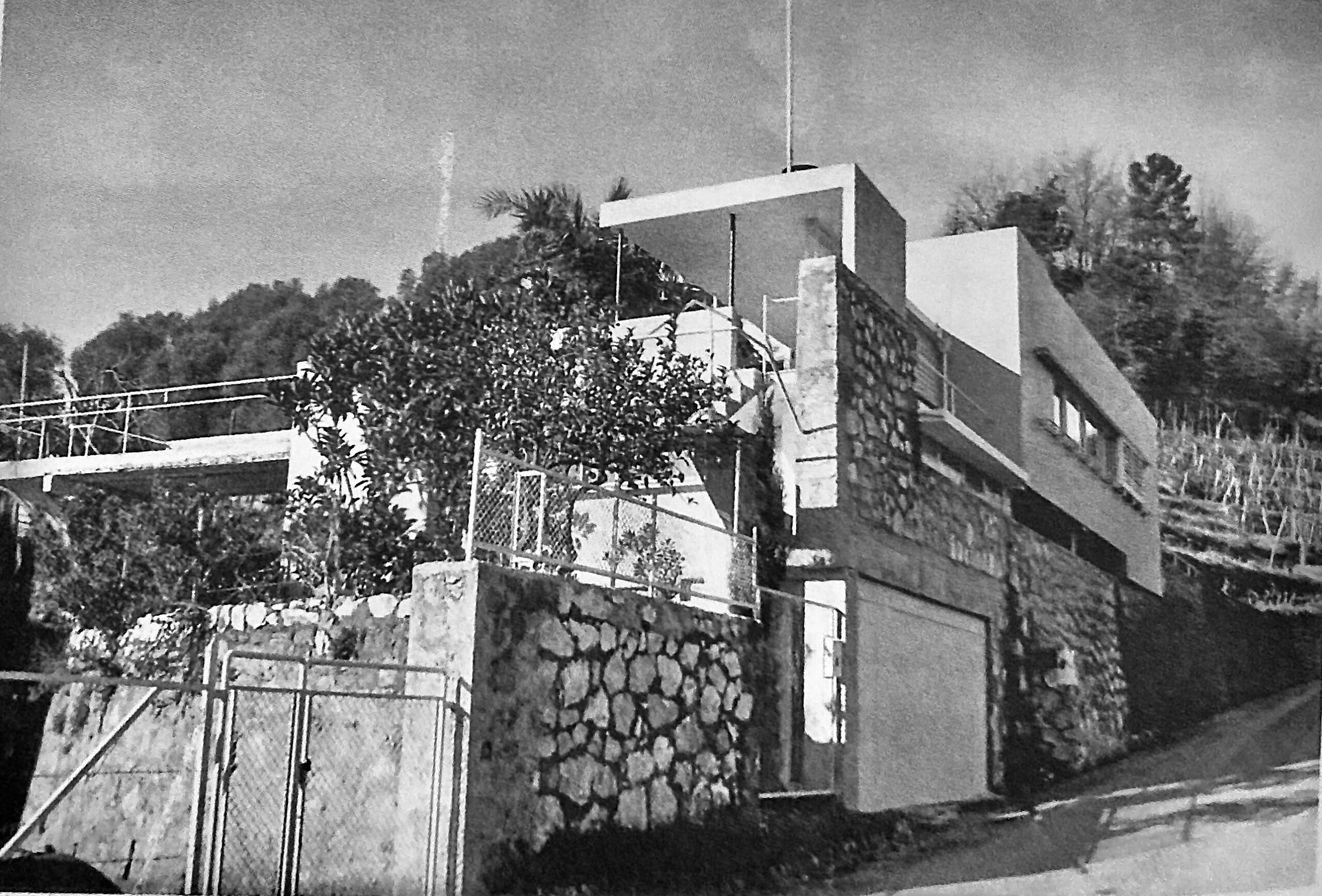

Those were Eileen’s feelings when she left E.1027. Around 1932 she was ready to move on leaving her creation and Badovici…the lifestyle there did not suit her. I read she did not bother to take her belongings. So where did she decide to build a house just for herself? Eileen chose Castellar…a small charming village up a winding road above Menton, France. She named it, Tempe à Pailla…her second architecture creation. It’s thought that the name comes from a Provençal proverb: Avec le temps et la paille, les nèfles mûrissent. (With time and straw the medlars ripen). Care and patience went into the house she would call her own.

While building E.1027, Eileen bought a small plot of land with wonderful views of both the sea and the Alps Maritime in Castellar, on the Chemin de Belvessasa. It looks as though the idea of building a house just for herself occurred early on. Castellar is approximately thirty minutes drive away from Roquebrune. On this small plot were a cabanon used for tools and shelter and a maison rural. At the same time, she bought two other plots…one across the road with 73 lemon trees and the other with vines. Together they gave her unobstructed views.

Tempe a Pailla in Castellar.

On April 24, 1926 the contract was signed buying the land from Jean Baptiste J. Viale, a farmer, for 68,000 francs…land total was one and one half acres. The existing house, Le Bateau Blanc, was built on top of a stone structure and three water tanks. To build on such a difficult site was exactly the sort of challenge Eileen liked. As Peter Adam puts it: “It gave her the chance to create a dramatic dialogue between the house and its site. She was never seduced merely by picturesque scenery.” She would prevail taking full advantage of the awkward terrain. Beginning in 1932, her new house would be built.

The cabanon on the property was torn down, the new structure was built on the water tanks. One tank was converted into a garage and a “small driver’s room.” The second tank was used for a cellar that was entered through the dining room and the third was kept to collect water. The new house atop the old stone structure was “embracing the curve of the road seamlessly combining the new with the old.”

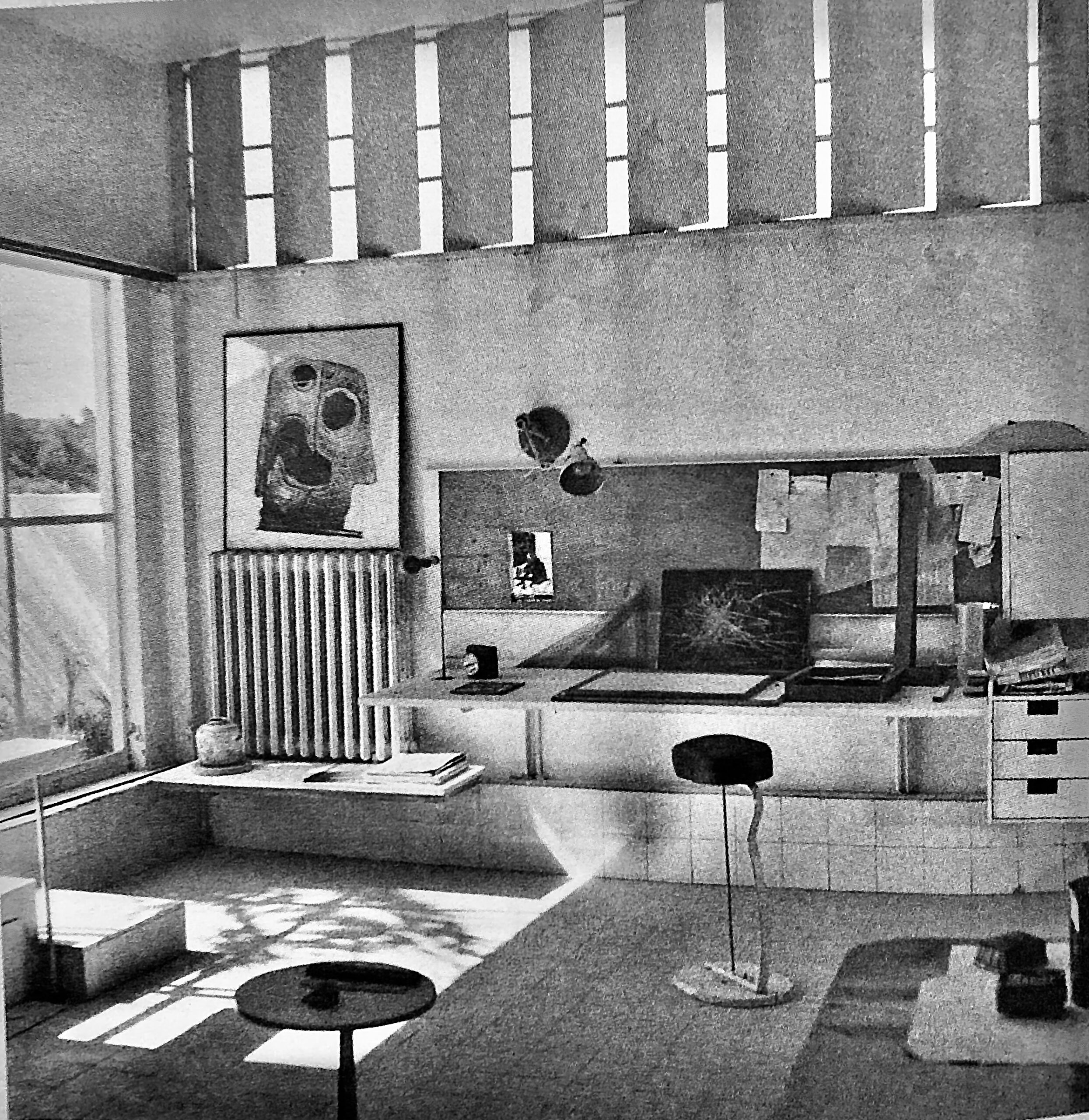

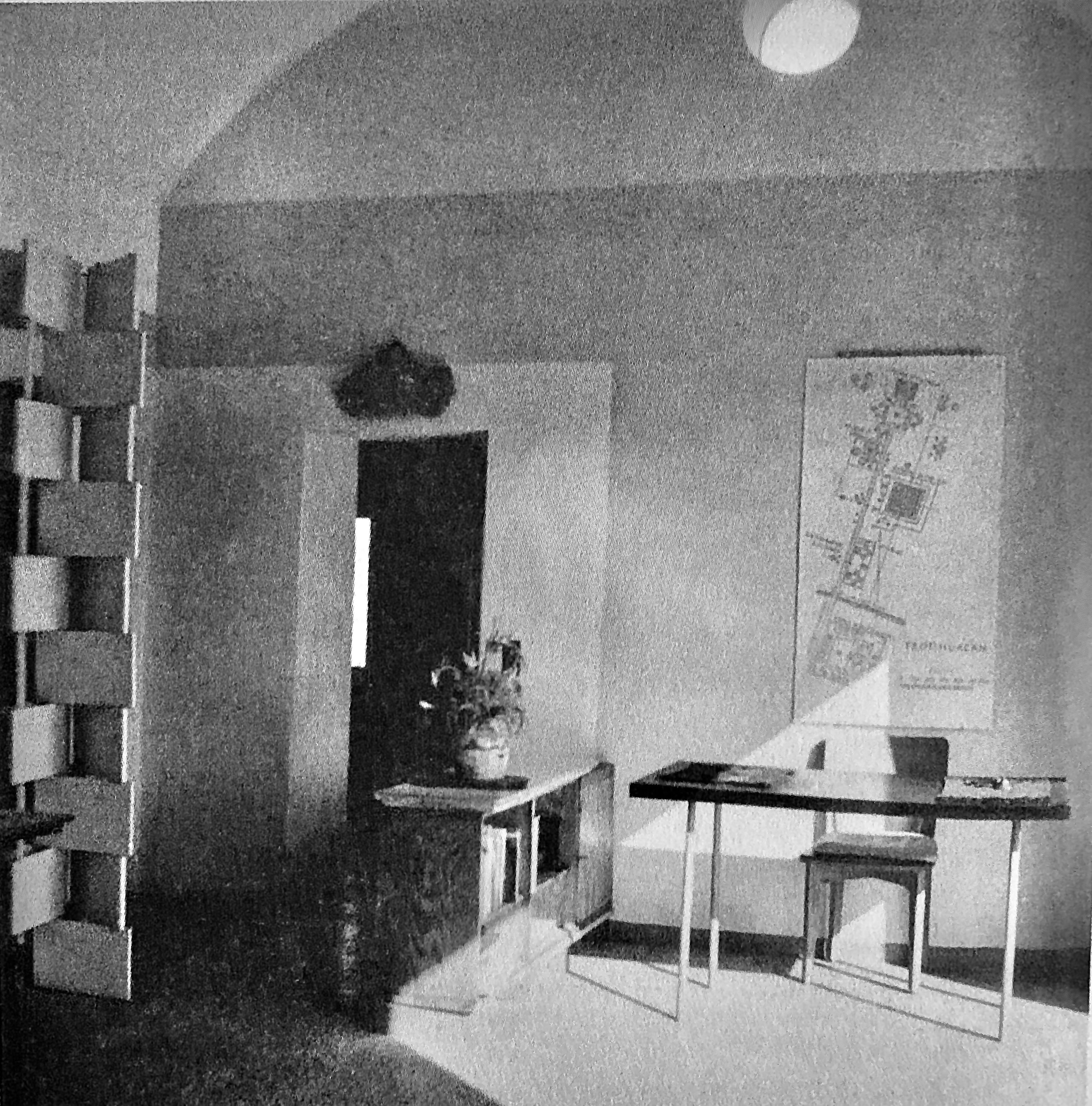

“The study area of the living room, with a bar stool [one of her designs] and a desk that could be folded up over the cork noticeboard on the wall.” Tempe a Pailla

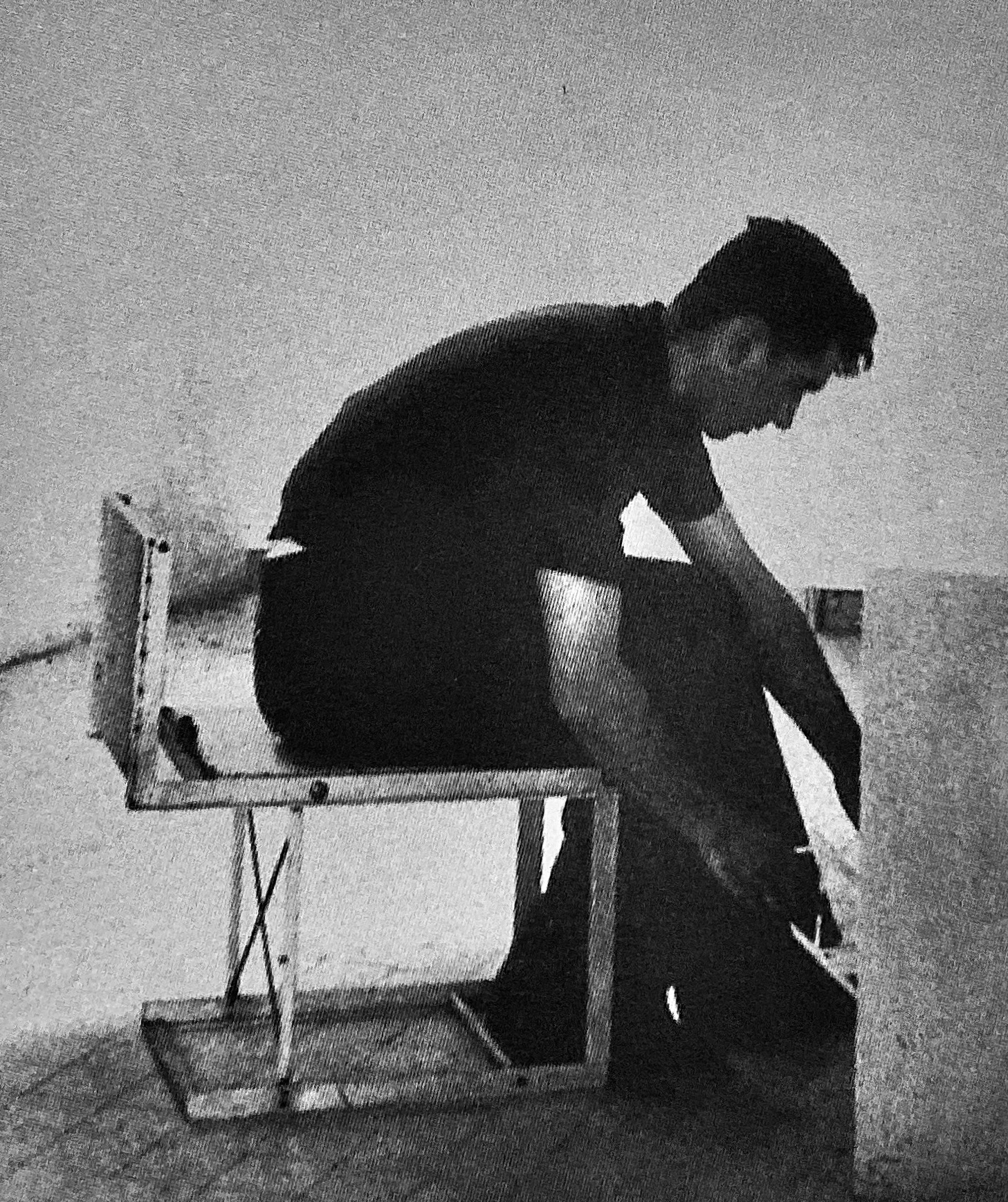

André-Joseph Roattino, the mason that built E.1027, was once again hired, along with two boys, to build her house. He lived in Castallar. He also “executed most of the furniture.” André-Joseph recalled how Eileen was “still driving around in a little MG, fussing over everything and never stopping until she had precisely what she wanted.” A mere 970 square feet of habitable space on two floors…smaller than E.1027. Peter Adam states: “For herself she was content with a living-working cell, a machine à habiter.” You may remember in my last article, first in the Eileen Gray series, that once she stated: “The engineer’s art is not enough unless it is guided by human needs…A house is not a machine à habiter. It is the shell of man, his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation.” In her house, although the space was small, it fulfilled her human needs and therefore it was perfect.

To enter the house one went through an iron gate, up a concrete staircase and over a concrete bridge. As at E.1027, ship architecture was the model. In the study-living room on one wall a desk folded into the wall when not in use. On the other side was a mattress on top of a raised platform. A terrace was accessible from this room extending the space. A wall with shutters blocked the road serving “as an outdoor living-cum-dining room and a black-tiled bed for sunbathing.” Indoor dining was also incorporated. Three bedrooms, one being the main bedroom, a bathroom and kitchen that accessed the outside. Each room had its own outdoor space.

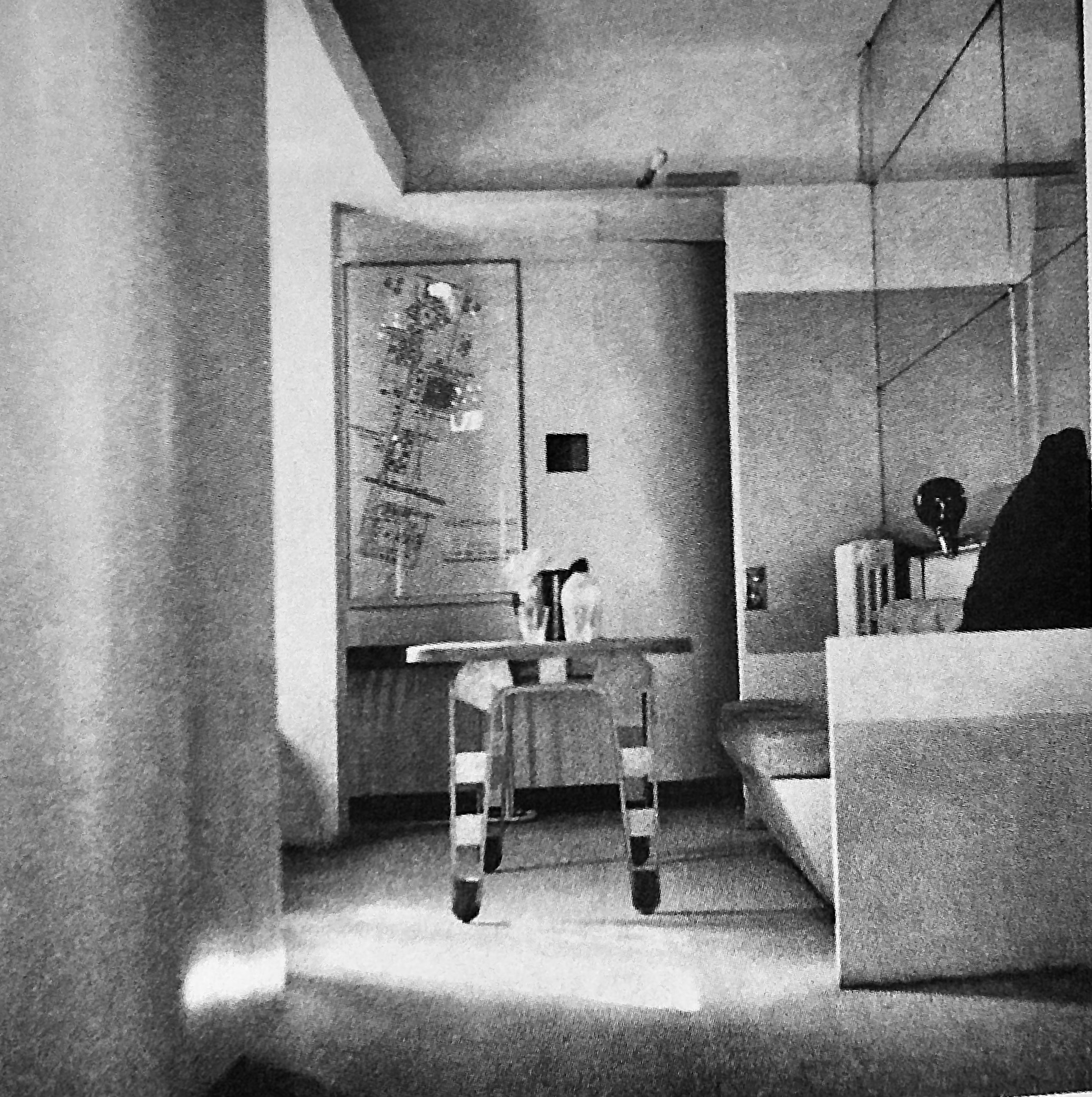

“The dining area, with a folding metal table and built-in bench against a mirrored wall.” Tempe a Pailla

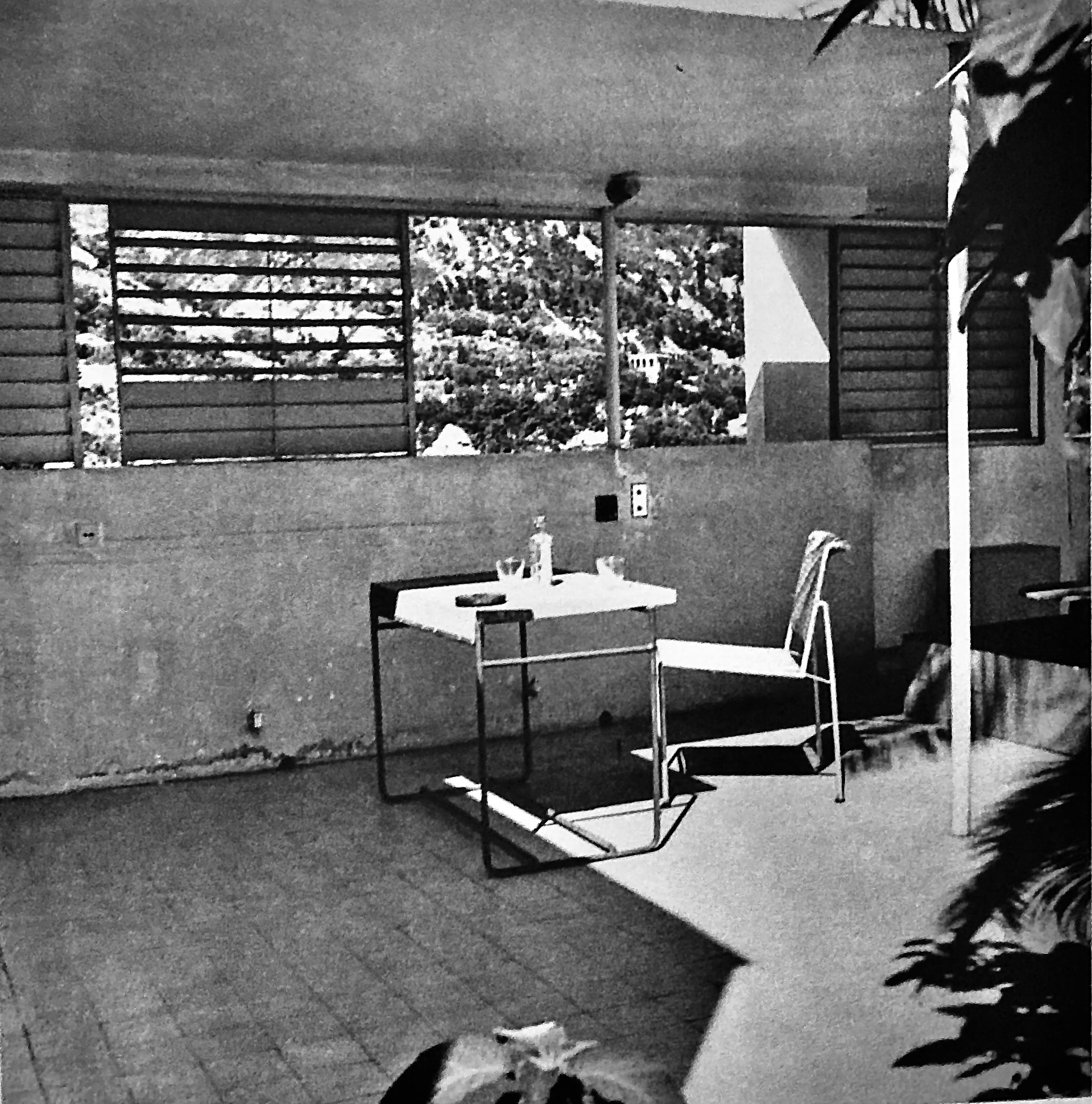

“The terrace, facing south, virtually a second living room, and partly roofed. If required, it could be closed in by sliding shutters. The dining table could be transformed into a low tea table.” Tempe a Pailla

Complete privacy, always a requirement for Eileen, was achieved with large windows only on the first floor. To allow light into the lower rooms, pantry and lavatory porthole style windows were installed and a translucent wall let in the light in the kitchen. The walls in some instances served as built-in furniture combining her creativity as an artist in furniture design and architecture. “Some of the items of furniture are inseparable from the walls and are an integral part of the architecture. Thus she created the feeling of spaciousness, freeing the space in the middle.”

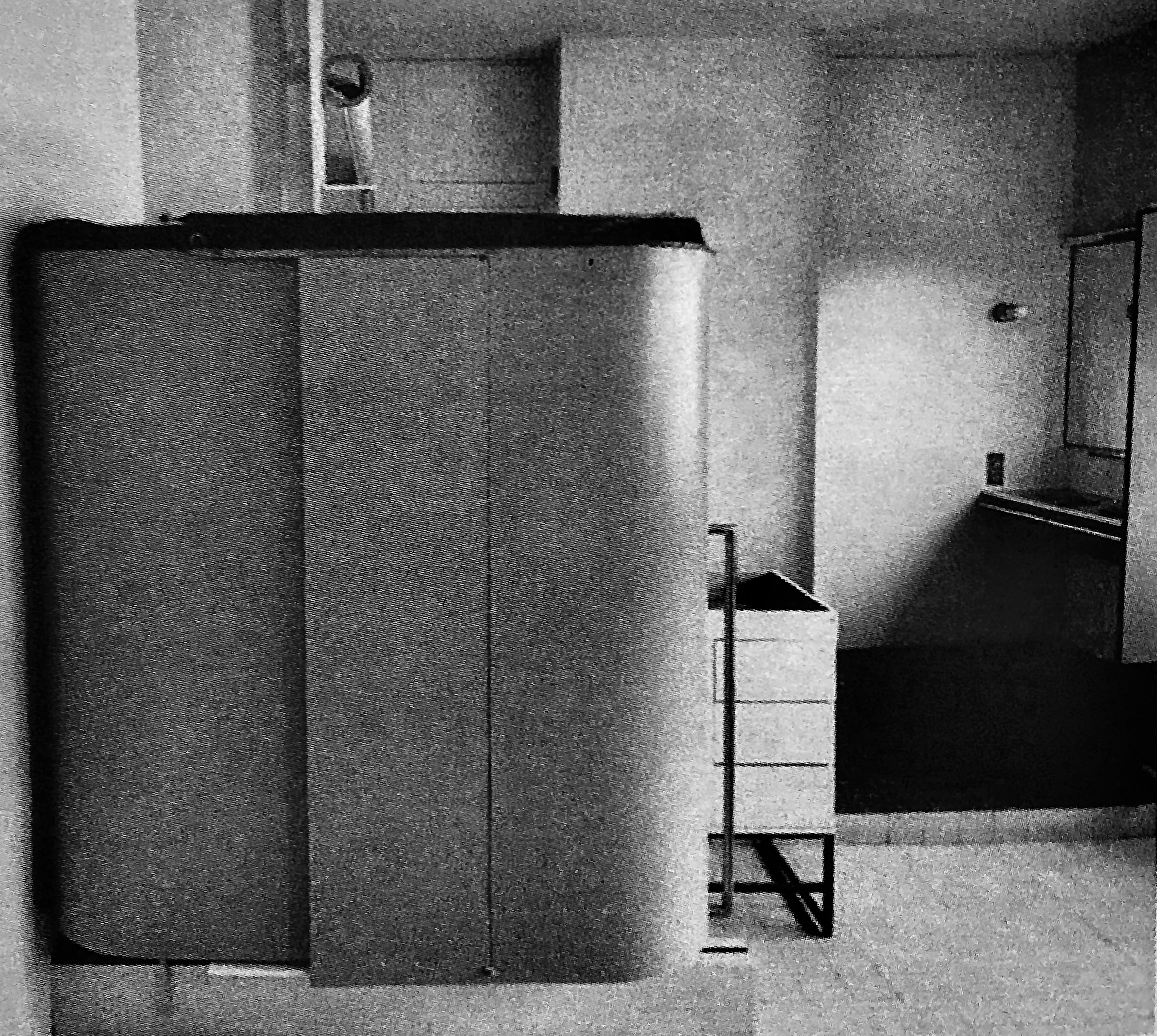

“The metal wardrobe hiding the sleeping area, with a perforated Plexiglass top, could be reduced or extended in size.” Tempe a Pailla

Another view of the metal wardrobe/sleeping area. Tempe a Pailla

Eileen was untrained in architecture design, but that gave her the freedom to adapt her ideas and make them work. She worked closely with the workmen, was “critical of her own design and to be flexible enough to alter it. It was the purest and most self-centered task. This gave the house its homogeneity.”

Peter Adam’s thoughts about the house in Castellar: “In its inner organization Castellar is more thought out, more sophisticated than E.1027…was built according to her own needs…entirely to her character. In it she felt herself again.” He goes on to state: “E.1027 was built for a man she loved with the idea of a communal life.” The interior of Castellar was completely designed by Eileen, extreme simplicity, as was the furniture designed for maximum usefulness.

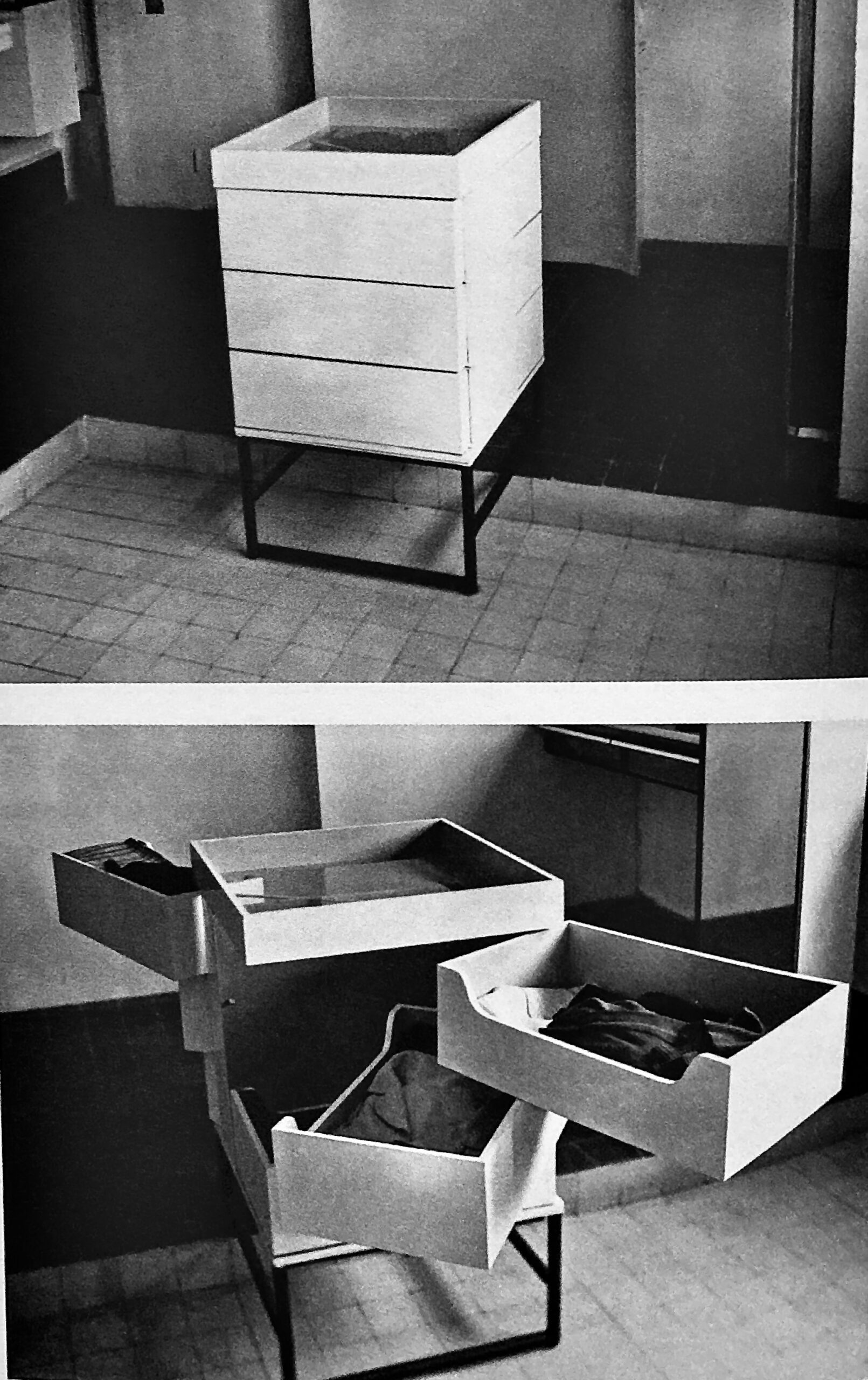

Cube chest…”the pivoting drawers had glass bottoms so their contents could be easily seen.” Tempe a Pailla

Adam describes the multi-function furniture Eileen created for Tempe à Pailla’s on page 213 of his book. “Castellar was a laboratory for modular living…A multitude of folding and sliding systems created ingenious storage spaces…in her hands the most ordinary object became extraordinary.” Decorators I’ve spoken to have told me that lighting is important to the overall design of a room. In great detail, on page 215 of his book, from notes found in one of her notebooks, Peter Adam relates her thoughts about lighting: “Work often with the psychology of light. Bear in mind that in our subconscious we know that light must derive from one point—sun, fire, etc. Need deeply anchored in us. To understand this explains the morose impression indirect light creates. Enlarge the light, amplify the rays which come from one point, don’t encapsulate it. Interior lighting: low lamps, light the floor by light spread out 80cm [2 1/2 feet] from the floor or illuminate the room at 1m to 1.5m [3 to 5 feet] from the floor. Eileen always made good use of natural light.” Every detail mattered to Eileen and Adam describes her creative attention to such detail beautifully.

André-Joseph Roattino. He made all of the furniture in Castellar. Here he is “sitting on a chair that could transform into a stepladder.” The photo was taken by Eileen.

In 1934, the day finally arrived when her house was finished. Water was connected and the name of the maison was changed from Le Bateau Blanc to Tempe à Pailla, “alluding to the need for time to elapse in order for things to mature.”, as the Provençal proverb suggests.

Eileen spent the first year of World War II in her house in Castellar. Her time there was cut short. One day in 1940 two gendarmes showed up at her door telling her she must vacate by eight o’clock the next morning. As a resident alien she was not allowed to reside by the sea…she had to move inland as did all the other foreigners. Wasting no time she packed what she could in her small car and left that very night…leaving so much behind. The thought of moving to England crossed her mind, but her feelings for France were too strong so instead she went to Lourmarin north of Aix. She chose not to live in the old castle that had been restored by “her old acquaintance, the architect Henri Pacon, and the two Martel brothers.”, nor the hotel where many of the refugees were forced to live. Instead, she rented a house in Lointes Bastides. This “very simple” little house with two rooms, had no bath and a small kitchen “with a primitive stove.” Eileen described in a letter: “I am writing at a table made of two planks in a house that looks on to the village street. Electricity but no [facilities] of any kind. Louise called it “la maison phantome”—everything comes rattling down if you touch it, parts of the stove come off and the doors and stairs double up and fall in.” (She was there with her friend, Louise, that had been living in Paris. Eileen had encouraged her to come to the south.)

The “before”… a stone cabanon. Of her three architecture projects, it would take this project the longest to complete, 5 years. But, it had a view and a vaulted ceiling. With those two things going for it it made for an easy decision to create Lou Pérou.

Louise took care of the house while Eileen spent her time experimenting and concentrating on her art as she did in the thirties in Castellar. She was very bored and felt isolated, as you can imagine, but while in her forced stay in Lourmarin she did produce drawings in gouache and ink and collages. Her art kept her mind active. I am reminded how painting was Churchill’s way of coping through difficult times, saying it saved him. Further adding to the difficulty she endured was that she had to leave her car in Saint-Tropez making her feel even more like a prisoner. Life in Lourmarin was difficult. Food was scarce, there was no coffee or milk and few vegetables—albeit in beautiful surroundings in the country, not being able to work, what she lived for, it took its toll.

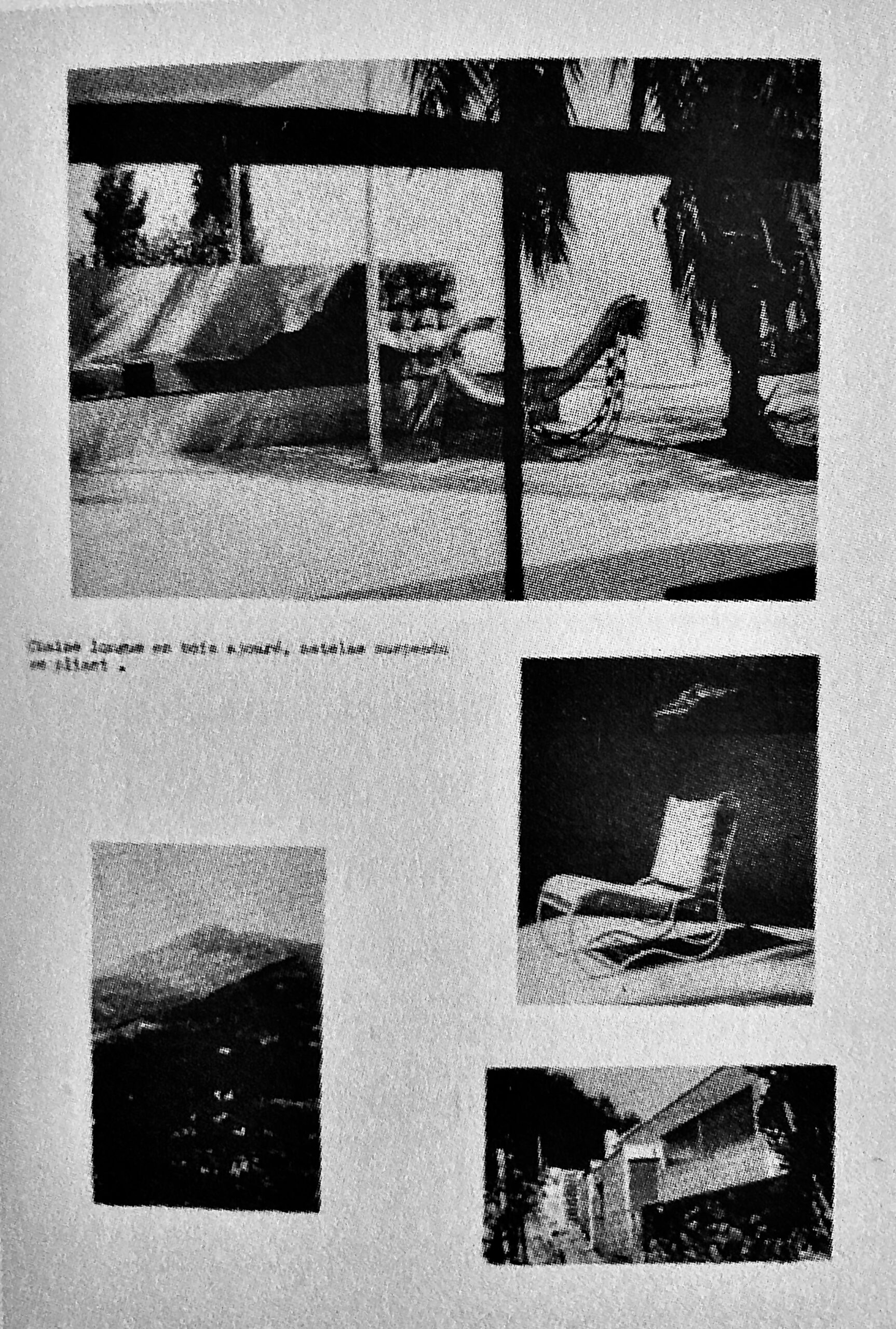

A page from her cahier showing Lou Pérou views and furniture she designed. |

A page from her cahier showing Lou Pérou views and furniture she designed. |

By the end of 1943 she was allowed to leave Lourmarin, but not permitted to to return to Saint-Tropez. The port of Saint-Tropez was blown up in 1944, a parting salvo of the retreating Germans. When she was able to return what she found was that her flat in Saint-Tropez was no more. Peter Adam writes: “The whole place was in ruins, including the furniture and the plans she made in Lourmarin. Eileen’s pygamas were floating in water. While Louise cried, Eileen looked on dry-eyed.”

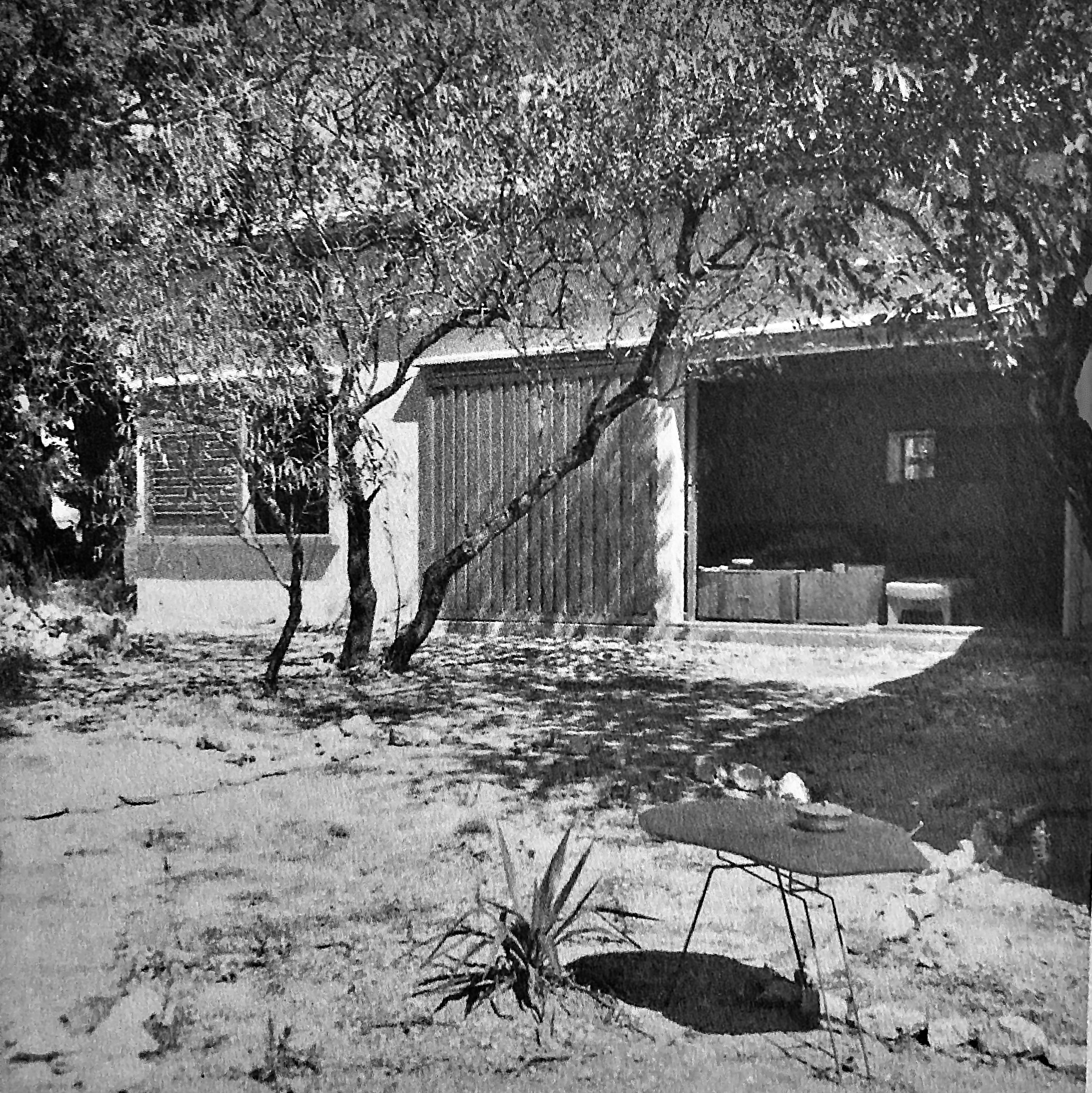

The south side of Lou Pérou with sliding glass doors that led to the terrace from the living room. In the foreground, notice the table she designed.

She and Louise took the train to Menton. They climbed up the very steep road to her house in Castellar. Seeing what the soldiers and smugglers had looted “she was unable to hold back the tear.” Peter Adam tells us all she had lost: “all of her personal clothes, china and household goods, but also her rugs and furniture, including a lacquered armchair from Jean Désert and three more armchairs. Gone were the divan, the cork-lined table, and a bamboo screen framed in wood that came from an African exhibition in Paris, which Eileen loved dearly. The thieves…had also ripped out all the built-in furniture and removed the mirrors from the walls. Her drawings and plans had been used to light fires.” In Eileen’s words: “The Germans have not only wrecked the house but cut down all the trees.” Returning to Paris to her apartment on rue Bonaparte, “She summed up her situation as follows: ‘I have saved nothing from Roquebrune, Tempe a Pailla has been looted, the little flat on the port was blown to bits by the Germans. There is nothing left worth keeping.’ ”

The living room in Lou Pérou had large glass windows to let in more light. The shutters were on rails.

Life was difficult in Paris, gas and electricity were often not available, but in her words after giving some thought to moving back to London Eileen is quoted as saying: “ ‘At least Paris is just as beautiful as ever—the morning mist and the plane trees shedding their golden leaves all down the quays,’ she wrote and a little later, ‘marvelous how people manage to dress at all at today’s prices.’ ” There came the time when she decided to take a look at her house in Castellar and determined that it was beyond repair to restore and building materials were not available. Rue Bonaparte would remain her main residence.

The Lou Pérou living room with furniture she had brought from her Paris apartment and E.1027. Notice her “Brick” screen on the left. The panels could be moved and adjusted for light or how she wanted it to look.

In July 1946, on a happy note, Eileen was able to go back to Saint-Tropez and got her Morgan…had it repaired and readied for the road. A short time later she rented a flat that Peter Adam describes as damp in Menton to reside while she began to renovate Tempe a Pailla. Yes, she did return and began the project that took seven years. Not surprising, the French building regulations had changed becoming more complicated since the Thirties. Because she had never taken French Nationality she “was not entitled to compensation for war damage to her property. Eventually she did receive a financial settlement, but recouped only a fraction of what she had lost.”

In 1953, she put Tempe a Pailla on the market declaring: “Castellar is finished.” But, after a lot of back and forth with the potential buyer this first attempt to sell eventually fell through… because there weren’t enough bedrooms. She was seventy-five at the time. Her deep love of Saint-Tropez was calling her back and she wasn’t living in Castellar very much. “The excitement and charm that Castellar had once been encapsulated for her was gone.” Her plan was to build in Saint-Tropez.

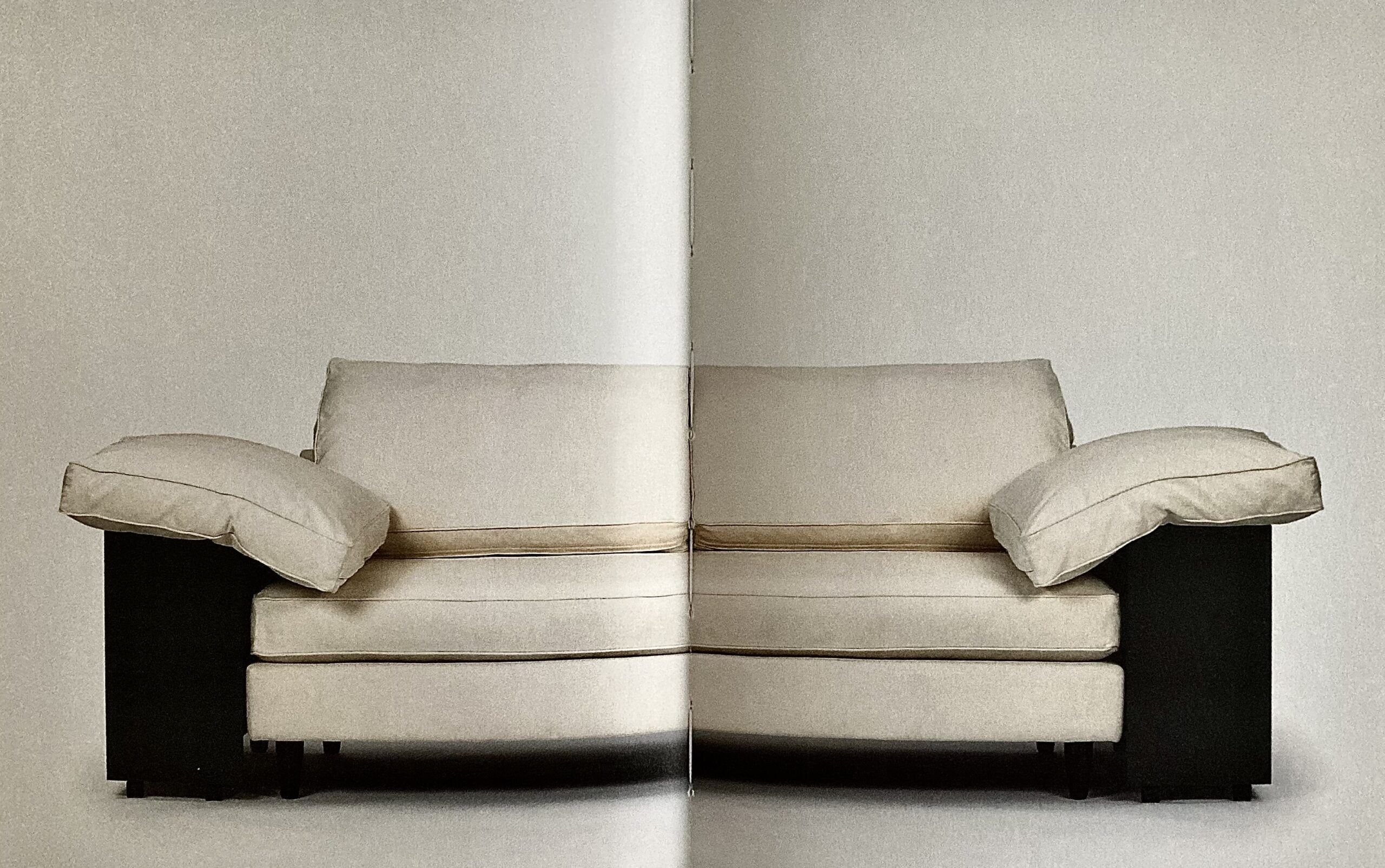

The Lota sofa (modern re-edition, ClassiCon).

Enter Lord Beaverbrook. He contacted Eileen expressing a desire to see Tempe a Pailla. He suggested that the artist, Graham Sutherland, was looking for a place to buy in the area. Sutherland and Beaverbrook would be “neighbors” as Beaverbrook had a house in Cap d’Ail. Winston Churchill was often a visitor to Beaverbrook’s house in Cap d’Ail. The sale of Tempe a Pailla went through in 1954 for 550,000 francs.

She wrote to her carpenter Roattino to tell him she had sold the house in Castellar. In her letter saying: “ ‘I am sad to have left Menton and to leave the country around Castellar. Up above the village there were lovely walks, but when I had my eye operation I had to sell my car and then things became difficult.’ Roattino sent her a crate of oranges and she returned the favor with a silk waist coat.”

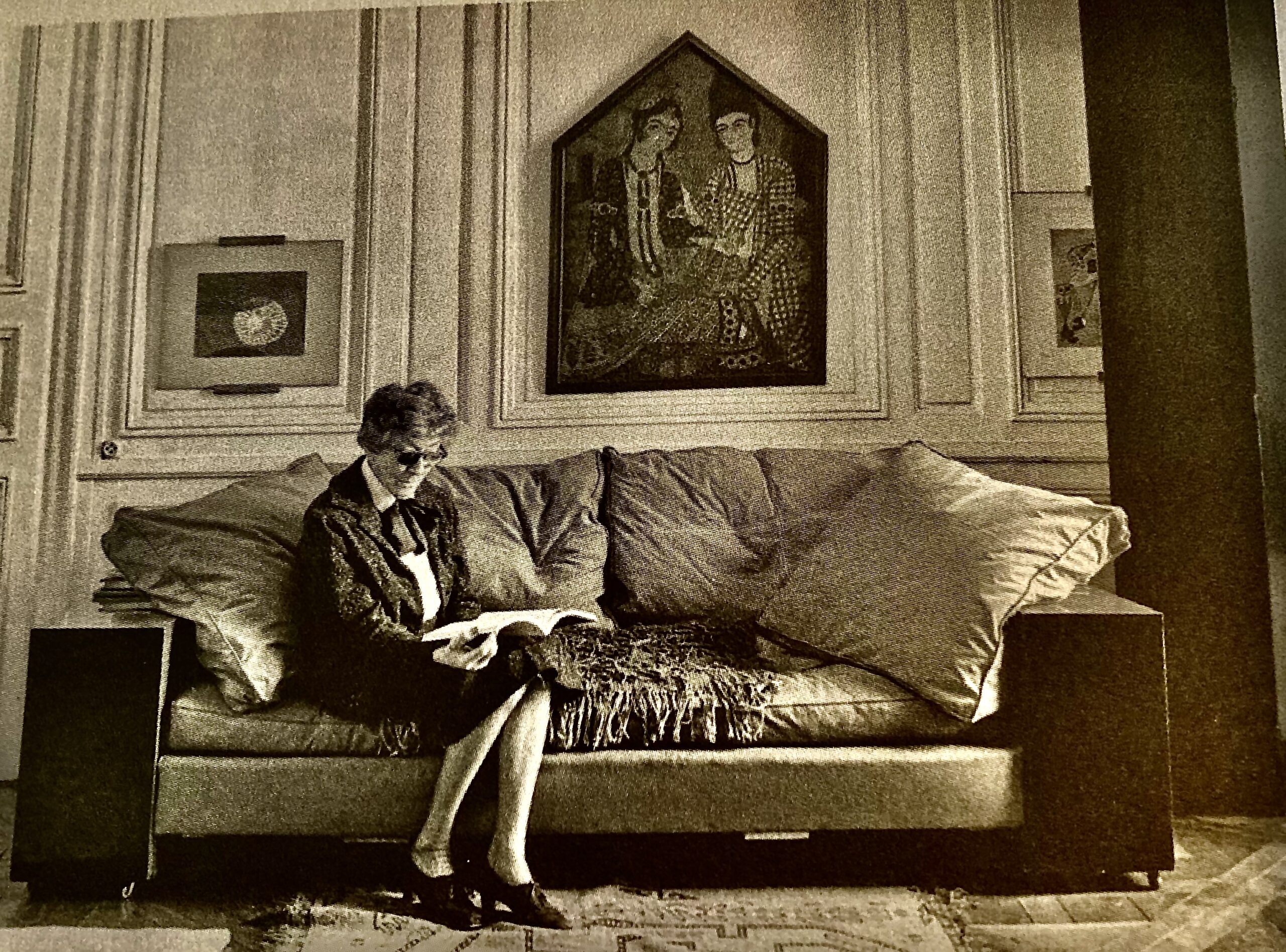

Eileen in her Paris apartment on rue Bonaparte. Eileen had originally designed the Lota sofa for Madame Mathieu-Levy.

At age seventy-five Eileen was not finished building. She would turn eighty when it was done. For years Eileen had been suffering from deteriorating eyesight and Parkinson’s disease, but that would not slow her down.

“In 1939, she bought a large stretch of vineyard behind Saint-Tropez for 72,000 francs. It contained a small abandoned stone building, which was essentially a cabanon. Although it only consisted of one room, it had a vaulted ceiling that Eileen loved. It was in the area known as Chapelle-Sainte-Anne, after the church that dominates the small hill.” Again, as in the past when choosing property, it was the view it provided. Always the view. She named it Lou Pérou. Begun in 1953 and completed in 1958 it was to be her third and last architecture project. Peter Adam states: “This house took almost five years to build and her energy sometimes seemed to fail her. She camped out in it when it was only half-finished, when the rain poured down for weeks on end and the roads were cut off by floods.” When completed, it would be her summer residence.

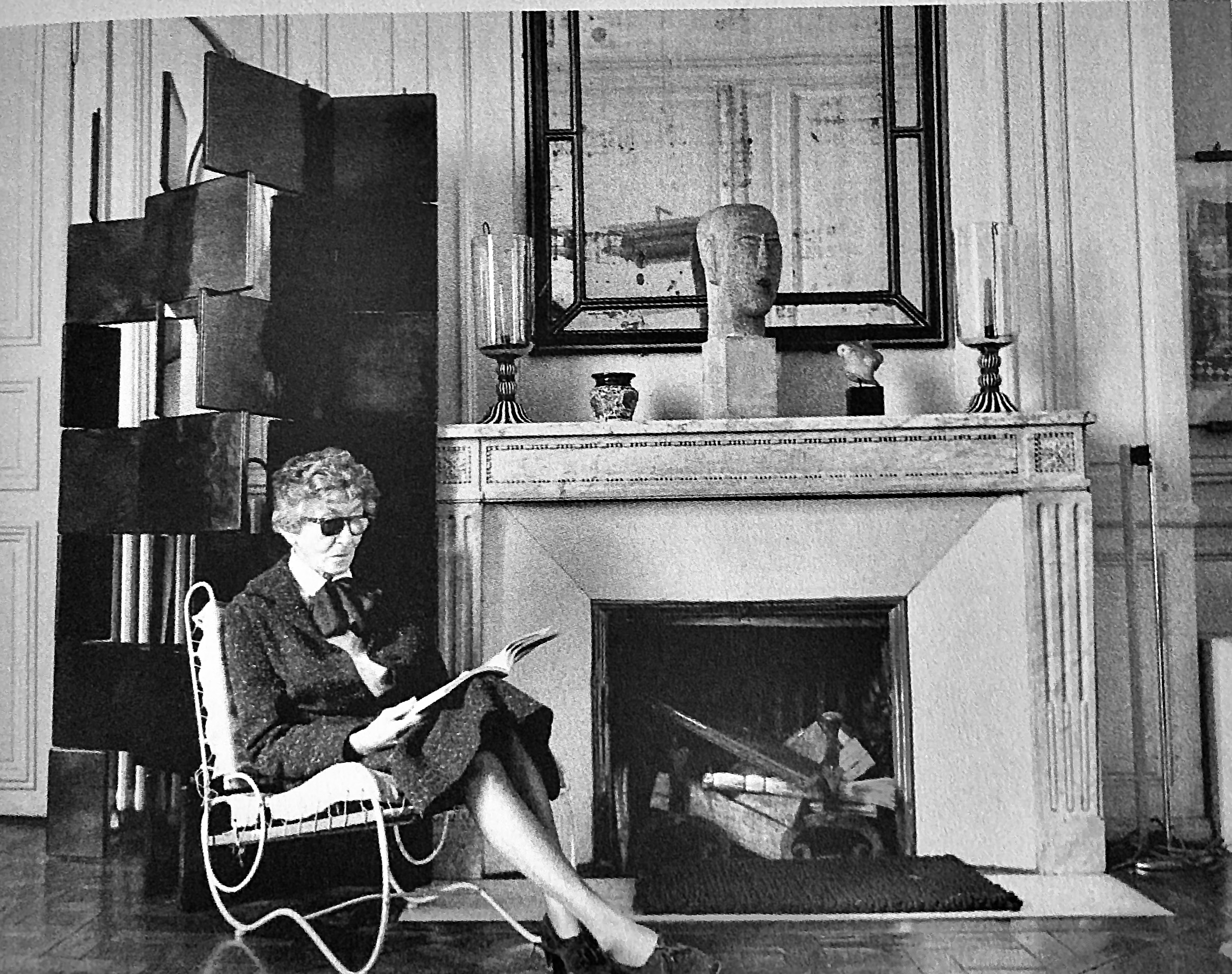

Eileen was about ninety years old as she is seen here in the drawing room of her Paris apartment. The curved white metal deck chair is from her house in Castellar. The screen is one of her designs known as the “Brick” screen created in the 1920s. Their geometric design was in stark contrast to Art Deco popular at the time. Once saying to her niece, Prunella Clough: “The screens are in revolt.”

“Prunella (Clough, Eileen’s niece) and I often went to Paris to be with her. She became increasingly conscious of being seen eating in public and stopped going to restaurants, preferring to take her meals at home. Fewer and fewer friends were in her life…It would become increasingly difficult to break the solitary pattern during the remaining years of Eileen’s life.”, Peter Adam.

I was moved by the lovely story Peter Adam tells at the end of his book, Eileen Gray—Her Life and Work

“One of her great pleasures was to go for a drive in the car, especially in an open-top model. One day she decided to visit E.1927 again. We set out towards Roquebrune and parked near the house. She stopped: ‘I can’t do it, it’s too late anyway.’ So we turned back. The shadows of the past always came back to haunt her. Instead we visited the new Foundation Maeght in Saint-Paul de Vence, built by her friend Joseph Lluis Sera, and spent hours examining every detail of the museum’s building.” As I have been there many times, a visit makes for a very pleasant afternoon. Or, perhaps before luncheon at La Colombe d’Or making it an even more perfect day.

Eileen Gray in silhouette. She was about ninety. (1878-1976)

A genteel Irish lady named Eileen Gray became a pioneer in the Modern Movement in architecture. Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel was a pioneer, a moving force in the world of fashion. Both had complicated lives, but through it all their determined natures and extraordinary talent they left an indelible mark in their respective fields. My interest in bringing their stories to the readers of Classic Chicago Magazine has been, in part, because both had a connection and a close proximity to Menton…the village that’s been a part of my life for thirty years. I hope if you are in this area of the Côte Azur you have a chance to visit E.1027, a unique and important—HAIKU in concrete—facing the sea.

À bientôt

Quotes and Pictures:

Eileen Gray—Her Life and Work, by Peter Adam, published by Thames & Hudson.

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Martin’s Press.

The Painter Le Corbusier, by Tim Benton, published by Birkhäuser.