BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

Bonnie Bell Pacelli shares this New Year’s resolution that should be near the top of everyone’s list. A former reporter for Newsweek and People, she founded Milestones, a Gift of a Lifetime in 2003 to assist people tell their life stories in their own words, with a book or video as their takeaway. She quotes Bruce Feiler, author of The Secrets of Happy Families: How to Improve Your Morning, Rethink Family Dinner, Fight Smart, Go Out and Play, and Much More:

“If you want a happier family, create, refine, and retell the story of your family’s positive moments and your ability to bounce back from the difficult ones. That act alone may increase the odds that your family will thrive for many generations to come.”

We asked Bonnie for her tips on capturing and sharing these memories.

Why should we tell our stories? Who are we writing for?

Everyone loves a good story! So it’s amusing to listen to reasons why not to tell our life stories. They range from ‘People will think I’m vain’ or ‘My life hasn’t been that interesting’ to ‘No one cares.’ Ask yourself, however, “At a certain point in my life would I have liked to be able to refer to the reminiscences of my parents or grandparents?” You have to think about a memoir from the perspective of those around you—family, grandchildren, and generations to come. They are the ones who will treasure a life story. In some cases, it is for heirs and employees of a family-owned business to understand the values upon which the company was built.

As a memoirist, I’m always intrigued by how much thought, effort, and money are spent on securing one’s financial assets. But what about preserving your intangible assets—your life experiences and personal values—not to mention the role of luck and timing in your life? There is an African proverb I like to cite: ‘When an old man dies a library burns to the ground.’

Why do you think there been a real emphasis lately on the writing and sharing of personal stories?

If you spend any time in bookstores or public libraries, it seems memoirs are among the hottest genres. One of the most popular features on National Public Radio is Story Corps, ordinary people sharing extraordinary memories. The day after Thanksgiving has now been unofficially named ‘A Day of Listening.’ Just look at the enormous interest generated by Ancestry.com.

I think one of the issues is that technology—not just social media, but cell phones, email, live news, and YouTube—has brought people closer together or forced people, depending on you look at it, to concede anonymity. It’s become increasingly socially acceptable over the last decade to open up your life to others. Memoirs, of course, still allow you to do that in a controlled way and limit your audience as well.

The New York Times summed up recently: ‘In an era when it seems every life is displayed on the social media for the world to see, a whole generation is getting older, and its stories, if not written or otherwise recorded, will be lost.’

I agree with that, but I also think there is a greater awareness across generations of the value of telling our stories. Several thirty- and forty-year-olds have asked me to work with their parents so that the family stories will not be lost. So even amidst our social media world, perhaps there is a yearning for permanence, something to hold on to. It’s a way of saying, ‘I was here and my life mattered.’

What has been, in your experience, the reaction of family members when they hear previously unknown family stories?

Usually it’s the children whose eyes are opened to some of the obstacles overcome or difficult decisions that had to be made. An adult granddaughter told me she had no idea how humble her grandfather’s childhood had been, and how hard he had to work to get the family where it is today. He never really talked about it. One client admitted that responding to my interview prompts about his childhood helped him retrieve memories he didn’t think he had.

What is the best way to get started? Where should we begin?

The first step is organization. I usually recommend labeling several folders according to different periods of your life: ancestors, early childhood, siblings, homes, holidays, schooling, career, marriage, family, vacations, and traditions. Keep a small spiral notebook with you and every time a memory, anecdote, or thought about your early life pops into your head, scribble them down—preferably not while driving—and stick it into one of the folders.

Choose a time of the day or the week that you will devote to the writing process and stick to it. Given our busy lives, this takes some discipline but be patient—it takes time for habits to take hold.

Think of your life story as a novel with you as the protagonist. It needs a beginning, middle, and an end. Remember: you are not a celebrated author, but the story of your life has immense value for you and your loved ones. Try to use as much vivid detail as possible: memories of your childhood home, the sound of a screen door that slapped shut, the smells of bread baking in the oven on a winter day, or the shapes of trees through a living room window.

Most people prefer to structure their memoirs chronologically; others like to talk about their life in a series of anecdotes or short stories. If you are working on a computer, you can always go back and rearrange the sequence of events or start from a life-changing event and then flash back to an earlier time. There is no right or wrong way.

What are ways to dispel writer’s block or other feelings of intimidation or trepidation?

Brainstorm! People need to get words and phrases down on paper. They can be reorganized and sentences and paragraphs will sprout from these seeds. People think they need fully formed ideas before they start writing, but they don’t. Once you start jotting down fragments, they will trigger successive ideas. People also feel like they need to write something brilliant or it isn’t worth writing, but writing is a process of rewriting. You should expect to revise again and again. Don’t get bogged down on the first draft.

Should we do a lot of research on the times we have lived in?

No. If people want to know what happened in the 1950s they can read a history book or go on Wikipedia. What’s important in a memoir is what happened to you in your life, and how events may have shaped you. What I do as your consultant is provide question prompts that help you recall what was happening around you at different stages of your life. Some families choose to do an expanded family tree. There is much information to be found on Ancestry.com.

Who are some of your favorite authors who have told their stories and why?

Katharine Graham’s Personal History is a favorite because of my experience as a reporter at Newsweek. It’s an honest account by the most powerful woman in publishing who suffered terrible tragedy in her life. It was also fun because I knew some of the characters personally.

Then there is Madam Secretary: A Memoir, Madeleine Albright’s telling of her days as the US Ambassador to the United Nations, and her rise in high-level government circles, to become the first woman to serve as Secretary of State. The first part of the book sheds light on her childhood in Czechoslovakia, fleeing with her family from the Nazis in the 1930s. Although raised Catholic, Albright would later learn that her parents had converted to the Christian faith from Judaism, and that three of her grandparents had died in concentration camps during the Holocaust. But what’s most appealing about her story is that Albright is self-deprecating.

One of my favorites is Tim Russert’s Big Russ & Me: Father and Son: Lessons of Life, a warm, charming memoir of the bonds of shared interests between a father and son in Buffalo in the 1950s. I still think of some of the lessons Big Russ taught his son. Another favorite is The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion, where she confines the memoir to recovering from the death of a loved one.

Finally, I recently reread Elie Wiesel’s trilogy Night, Dawn, and Day, the first a haunting account of the author’s childhood imprisoned in the Auschwitz and Buchenwald concentration camps; the latter two novels based on Weisel’s life as a political activist and human rights advocate. His style of writing is more beautiful with each reading.

Tell me about yourself. Are you the family historian?

Yes, the role of family historian fell to me de facto, in part because of my background as a journalist. I am one of four sisters—I pity my poor father, but he was game about it. He grew up on a cattle ranch in Cheyenne, Wyoming, the youngest of six sons. The story goes that he put his saddle on the back of a train, headed east to college, and never looked back.

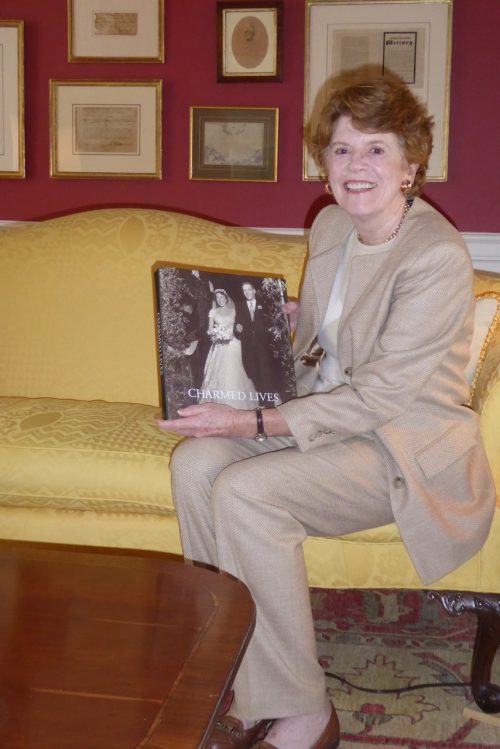

He told wonderful stories, and I regret that I never recorded them. My mother was a radio actress in the early days of Chicago radio, playing various roles in soap operas on NBC Radio and WGN. She was a larger-than-life figure who loved to sing and had a flair for the dramatic. After our father died, I was determined to capture her life story. It took a while, but when it was published she was overjoyed.

How did you get started writing?

I have always loved words—how they are arranged on the page, how they can be rearranged, and how carefully chosen words provide an immediate visual of a person, a gesture, or a place.

Growing up, I read all the classics, Anne of Green Gables, Little Women, Charlotte’s Web and the Beverly Cleary series. Later, I enjoyed reading the business section of the Chicago Tribune and Time or Newsweek. After graduating from college, I found a job on Wall Street in the research department of a large brokerage house, editing the company’s analyses on companies for stockbrokers. On a whim, I applied to Newsweek, and said I would like to work for the magazine someday but only in the business section. As luck had it, I received a call several months later that they had an opening for a reporter in that area. A number of years later, I returned home to Chicago and was hired as a Midwest correspondent for a new publication being launched by Time, Inc. It was going to be called People Magazine.

Tell me about your business and how you enjoy people talking about their lives.

Someone said the greatest gift you can give a parent or grandparent is the opportunity to reminisce. It’s so true.

Milestones was a natural extension of my work at People Magazine, where I honed the art of interviewing and quickly getting to the essence of the newsmaker’s life. At times, I felt like I was on a commando mission, diving into remote areas for several days of interviews. But I am grateful for the experience of interviewing scores of artists and authors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, politicians, and celebrities.

In everyone’s life, there are so many surprising twists and turns—milestone moments that are fascinating. Because these are full-length books, clients have the opportunity to expand on certain areas their lives that were especially important to them. In the process, I get to know a client and his or her family on a personal level. It’s wonderful. To this day I exchange Christmas cards with many of my clients.

Are there comments you get from your clients that you might not have expected—things they have learned?

One client decided his life story was too short, and he wanted to expand upon it. I couldn’t argue with that! The chairman of a Fortune 500 corporation had me interview dozens of business and social contacts that had touched his life in different ways. Some were humorous in their assessment of him, others quite frank. It was an enormous undertaking but it added a rich dimension to his life story—and the client thoroughly enjoyed their candid descriptions!

How is telling our stories beneficial in terms of well-being? Are there times when it produces sadness, and how do you deal with that?

Psychology professor Dan McAdams and his colleagues at Northwestern University asked 269 midlife adults and 125 college students to tell open-ended stories about meaningful episodes in their lives. The stories were blind rated and tallied as ‘redemption sequences,’ in which bad events have good outcomes and ‘contamination sequences,’ in which the reverse happens.

People who told stories with many redemption sequences also tended to score higher on McAdams’s ‘Generativity Scale,’ a concept pioneered by Erik Erikson as the desire to provide for future generations and make the world a better place, including passing along knowledge gained through experiences. Regardless of the story’s overall tone, participants who told redemption sequences also tended to be happier. Highly generative adults often tend to be volunteers, mentors, and political activists.

Other studies have shown that people who work through sadness and anger stemming from childhood tend to have a sense of satisfaction and stronger ego development. There are indications that individuals in hospice care who are given the opportunity to share their life experiences develop feelings of self worth; the feeling of being valued just by being listened to at a time of great distress in their lives.

Dr. Marshall Duke, a psychologist at Emory University, studies families and ways to counteract the forces that cause family breakups. Duke found that children who have the most self-confidence have what he and his colleague Dr. Robyn Fivush call a strong ‘intergenerational self.’ They know they belong to something bigger than themselves.

Duke also pointed out that families that adhered to traditions—even the hokey ones such as his family’s tradition of hiding turkeys and pumpkins in the bushes on Thanksgiving so the children could survive like the Pilgrims—create a bond for families.

Even telling children about unpleasant events at the appropriate time can be used to teach them about the importance of such qualities as resilience, forgiveness, responsibility, and compassion, Duke found.

So this year, why not tell your story!

To learn more about Bonnie Bell Pacelli and Milestones, visit www.YourMilestones.net or e-mail her at bonnie@yourmilestones.net.