The City’s Earliest Enduring Dynasty

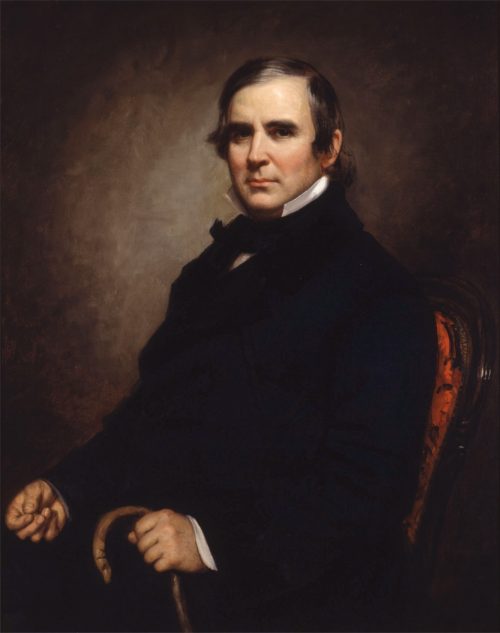

William Butler Ogden, Chicago’s first tycoon.

By Megan McKinney

Welcome to Chicago Aristocracy, a new series of Classic Chicago features. Within our city and suburbs today exists an authentic aristocracy, consisting of descendants of the 19th century tycoons who created the city’s great businesses and, in some cases, world-wide industries. An amazing number of the heirs of Chicago’s great fortunes have remained in the Chicago environs and continue to live within the conventions of their ancestors.

Initially, real estate was not merely the principal business for those making money in Chicago, it was the only business—and it was big money for the time. Everything else existed as part of the usual support system within any community. The boom occurred in the raising of funds to connect North America’s two major water systems–the Great Lakes and the vast Mississippi leading to the Gulf of Mexico. Existing waterways that might have joined the two ended a distressing 96 miles apart, requiring construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal to link them.

To finance the canal, in 1830, government land on which the little village stood was divided into “canal lots” and put up for sale to the public. The response was thundering, and nation-wide. Many of Chicago’s early real estate moguls never saw the city at all; they were Eastern financiers seeking to invest extra cash for big, fast return. And it was fast, a great game for all who participated–until it collapsed.

William Ogden

William Butler Ogden experienced much of the real estate drama. The young lawyer, born in Delaware River, New York in 1805, was brother-in-law of Charles Butler, one of the Eastern investors. Ogden, acting on Butler’s behalf, traveled out to the city to inspect the investment.

When he examined the property, a muddy forest that preceded Chicago’s smart Near North Side, it was the day after a virtual monsoon of heavy rains. As Ogden began attempting to walk through the area, he could not.

Each step took him further down into what he reported was a knee depth of mud and marsh. Although he wrote his brother-in-law that he—Butler—had “been guilty of an act of great folly” in making the purchase, Ogden stayed to supervise the draining of the land and construction of roads between its lots. However, when he put up Butler’s lots at auction, a mere third of the soggy land realized a stunning $100,000.

That changed everything for William Ogden, who then became so intensely drawn to Chicago’s potential that he resigned his position as a New York state senator to relocate to the developing community. A year later,1837, the town was incorporated as a city and William Ogden elected as its first mayor.

Ogden, whose childhood sweetheart had died tragically weeks before they were to have married, would remain a bachelor until old age. Thus, there was no reason to wait to settle down permanently, and he wasted no time in ordering a great house built for himself, his mother and his sister.

He summoned New York architect John M. Van Osdel, above, who designed a large Greek Revival residence with a rooftop observatory on four acres of Near North Side land. An avid admirer of horticulture, Ogden hired a European gardener to cultivate his grounds and installed a glass conservatory in back of the house. The mansion quickly became early Chicago’s social center, with the handsome, convivial Ogden serving as a hospitable host who threw large parties and entertained guests with sing-alongs in the parlor to his piano accompaniment. VIPs visiting Chicago invariably stayed at his estate and notable guests included William Cullen Bryant, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Samuel Tilden, Martin Van Buren and Daniel Webster.

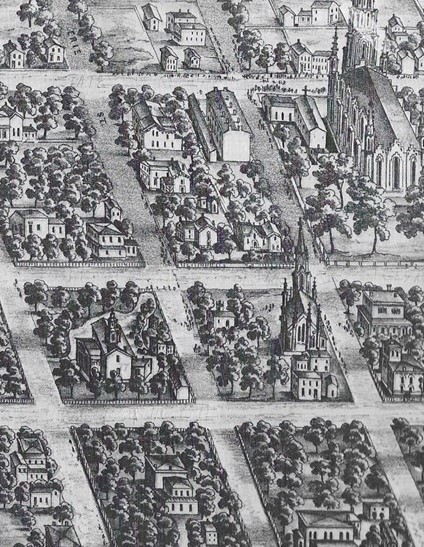

We have published this 1857 view of a portion of the Near North Side before. It is courtesy of Daniel Bluestone’s marvelous book, Constructing Chicago, with the Ogden compound in the second tier from the bottom, the first full block from the left, bordered by Rush and Erie Streets, Wabash Avenue and Ontario Street. St. James Episcopal Church is in the block to the right in this illustration and Holy Name Church in the upper right. Both would become the cathedrals we know today.

Ogden’s persistence, enterprise and single-minded determination created the first legacy of great wealth that continues to be enjoyed by Chicago’s 21st century heirs. Following one term as mayor, he continued to serve regularly as alderman, recognizing that to protect his investments it was necessary to be active in local government. He continually campaigned for city taxes to pay for streets, sidewalks and other vital infrastructure and, when unsuccessful, he raised the monies on his own. Although the initial money was made in real estate, Ogden became a serial entrepreneur; whenever he saw a need he created a business or industry to fill it. When Chicago needed a brewery, he founded a brewery, he financed banks, owned a steamboat company, bought hundreds of thousands of acres of Wisconsin pineland with their accompanying sawmills and, at one time, was partner with Cyrus Hall McCormick in his Reaper Works. Most notably he led the industry that would transform the nation during the latter part of the 19th century—the railroad.

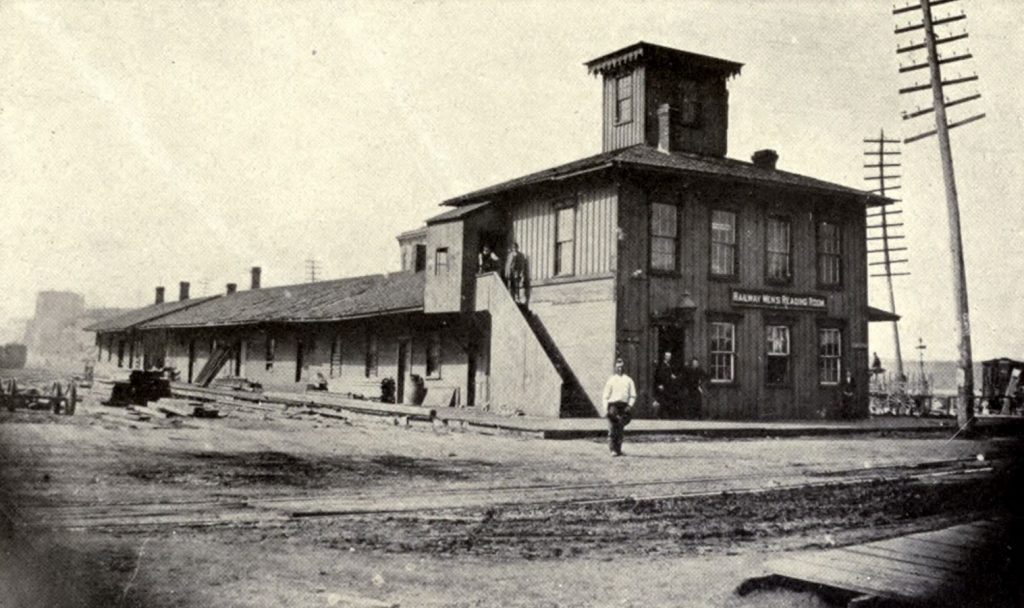

The Galena and Chicago Union Railroad. Its engine, the Pioneer, became a famous “personality”.

It was during1848 that Ogden won charter rights to create the city’s first rail line, the Galena and Chicago Union. Donald L. Miller, author of City of the Century wrote, “By 1848 he was the most powerful capitalist in the West.” And 21 years later, with the driving of the Golden Spike, Ogden would become first president of the Union Pacific, the world’s earliest transcontinental railroad.

The Galena and Chicago Union Railroad created Chicago’s first rail station at the corner of West Kinzie and Canal Streets.

By 1871, Ogden’s business interests were keeping him in New York for much of the time; he was at Boscobel, his villa at the northern edge of Manhattan, when he learned that fire had destroyed the city he had been so instrumental in building. He left immediately by express train to return to its desolate remnants. When picking his way through the debris he stumbled upon his own home. “I came to the ruined trees and broken basement wall,” he later said, “all that remained of my more than thirty years pleasant home.”

William Ogden was a public-spirited citizen, whose pro bono activities went beyond the generous contributions of money he donated to the city’s charitable and cultural organizations. Among the institutions he and his peers founded were the Chicago Historical Society, the old University of Chicago–where Ogden served as president of the board of trustees–Rush Medical College, Northwestern University and the esteemed Chicago Relief and Aid Society. The last was for many years the city’s premier charity and humanitarian organization and one that conferred great social cachet upon its supporters.

But Ogden’s great love continued to be real estate, and among his holdings was a large parcel of land along Lake Michigan north of the Chicago River, known as The Sands, which he purchased with the aid of his attorney, Abraham Lincoln, and cleared of the scruffy riff raff camping out there. During the past several decades, this southern portion of Streeterville–created in 1857 as Chicago Dock & Canal and reorganized as a real estate trust in 1962–has been the site of some of the city’s most dynamic development, further increasing the wealth of his heirs.

The childless Ogden left an estate valued at $10 million in the economy of 1877, including monies that funded the graduate school of science at the University of Chicago. He also bequeathed a generous chunk of Chicago Dock & Canal to a niece, Eleanor Wheeler, who married Alexander Caldwell McClurg, another extraordinary Chicagoan.

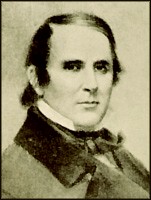

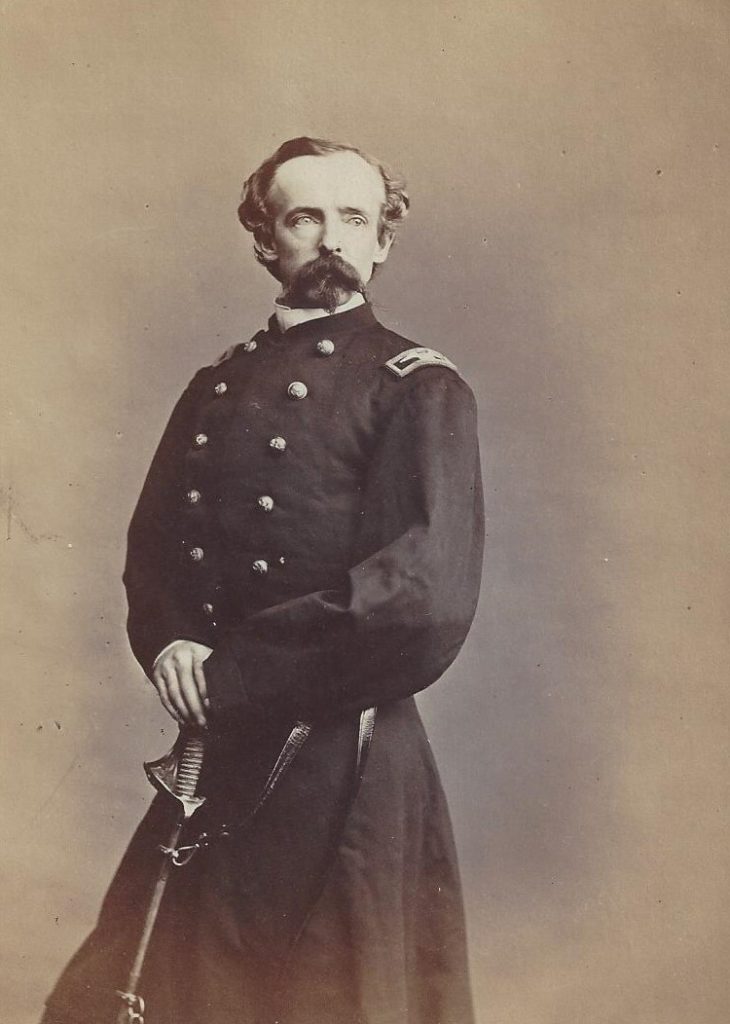

General McClurg.

The scholarly and resourceful Alexander Caldwell McClurg had moved out to Chicago from Philadelphia as a bookseller before the Civil War. He enlisted as a private in the Illinois State Militia at the war’s beginning, emerged a brigadier general at its end, and is said to have carried a copy of “A Golden Treasury of English Verse” with him throughout. Following his discharge, he set about establishing A.C. McClurg & Co., a publishing house and book wholesaler that, by the mid 1870’s, was not only the largest book company in the West but also had a reputation for being the most literary. During the latter part of the19th century, the McClurgs lived in a stately home in the 1400 block of North Lake Shore Drive, then a quiet street lined with trees and a clear view of the Lake.

Because the erudite General McClurg believed in a classical education and was dissatisfied with available public schools for his son, Ogden Trevor McClurg, he imported two tutors from the Roxbury Latin School in Massachusetts to teach the boy and the children of a few friends. Not wishing to leave the teachers unemployed when the job was finished, the general financed them in establishing what is now the highly esteemed Latin School of Chicago.

In 1911, when he was in his early 30s, Ogden commissioned the eminent architectural firm Marshall & Fox—led by the extraordinary Benjamin Marshall–to design 999 Lake Shore Drive, the apartment building that anchors elegant East Lake Shore Drive. At the time of its construction, the now elegant extension of Oak Street was in a swamp of mud. According to legend, during the building of 999, Ogden would go out on Sunday afternoons, sit in the building’s shell with a gun, and exchange shots with the notorious squatter Captain George Wellington Streeter, who lived in a homemade shack a few blocks away.

Eleanor and Alexander McClurg’s 21st century Chicago descendants are members of the intensely private Potter family, who include Ogden McClurg’s grandchildren, and live quietly under the radar of the media’s “Richest” lists in the greater Chicago area.

Further segments of Publisher Megan McKinney’s new Classic Chicago series, Chicago Aristocracy, will continue periodically during the coming months.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl