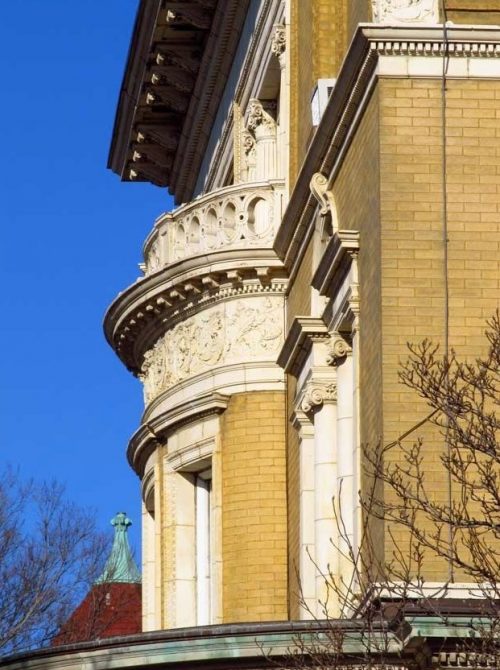

This elegant Ellis Avenue house would be the Swift family home —but not yet.

By Megan McKinney

When Gustavus Swift moved his family to Chicago in 1875, it was to a house he rented at 4363 South Emerald Avenue. The working-class Emerald ran between Halsted Street and Union Avenue, a convenient half mile from the stockyards. But it was far away—in every sense—from the new ultra-fashionable Prairie Avenue, where Gustavus’ colleague Philip D. Armour and other Chicago tycoons lived.

Prairie Avenue

In the snooty words of Arthur Meeker, Jr., chronicler of Chicago’s 19th century moneyed set, “At a time when old P. D. and his wife had long been ensconced on their sunny street among the sifted few, the Swifts were living in tribal obscurity in some bizarre neighborhood back of the Yards—was it called Emerald Avenue? To this day I don’t know precisely where was.” As noted in a previous segment of this series, Swift was from rare Mayflower stock, with nothing to prove to parvenu Chicago.

He and Ann, had been married 14 years in 1875 and were then parents of five. Louis was13; Edward, 12: Annie May, eight; Helen, six; and Charles, two. Little Lincoln, born in 1865, had died at two in 1867. There would be five more children in the next ten years: Bert, George, Gustavus Jr., Ruth and Harold.

These are the dreary houses in which the Swifts’ Emerald Avenue neighbors lived.

Within little more than a year Gustavus ordered a much larger, “modern” house built at the corner of Emerald and 45th Street. The generous proportions and smart style of the house, which incorporated the wonders of indoor plumbing and a furnace, made it widely discussed throughout the area. But the Swifts were still living on the working class Emerald Avenue.

Philip Armour had arrived in Chicago the same year Gustavus appeared. They would be friends, close stockyards neighbors, and–with Nelson Morrris trailing a bit behind–the three most powerful men in the city’s great meatpacking industry. It was Armour, with Marshall Field and George Pullman, “the trinity of Chicago business,” who created the allure of Prairie Avenue, to which virtually all of the city’s tycoons then moved. Of the era’s true giants, possibly only Swift and Potter Palmer did not follow. And Palmer created his own posh world, which would soon more than rival the South Side street that held the “sifted few”.

Gustavus in 1880, when he had been in Chicago five years.

As buried in work as he was, often leaving the house at five in the morning, Gustavus rode his tall grey mare home for lunch each day. There was work at home as well. Until a year or so after the move to Chicago, Ann kept his books and managed details of his business, on which they might work together in the evenings.

Dinner was an event most nights. Seated around the table were members of the family of seven, visiting relatives, Chicago friends, various children’s companions and sometimes those who were almost strangers. Gustavus remembered with gratitude the hospitality extended him during his travels about the Cape buying and selling livestock as a boy. During the Chicago years he was known to bring home lonely appearing travelers—particularly during the year of the 1893 Columbian Exposition—to join the family for dinner.

Occasionally there were evenings with just the family. The Swift’s daughter, Helen, wrote about what the rare evening without myriad guests might hold in store.

“Mother was a slip of a girl when she was married, weighing only ninety-eight pounds…I think she never felt heavier to Father. He would pick her up and carry her about as I’m sure he did when she was a bride.

“In the dining room was a square refrigerator about five feet high. I have often see Father pick Mother up as if she were a child and set her on the ice-box. She would blush a vivid crimson and say, ‘Gustavus, how can you? Don’t be silly. Take me down!’

“’You know, Ann, I like the looks of you up there,’ Father would say, with a sly smile, and his strong hands held her.

“Finally, ‘Gustavus, if you don’t let me down, I’ll kick you!’

“’Then I’ll just have to hold your feet.’”

Ann Swift was a delightful, highly intelligent companion for Gustavus. Not only was she able to manage the business affairs of a mushrooming business and meticulously keep its books but she had also taught school on Cape Cod before her marriage. Bearing eleven children and rearing ten was not unusual in the mid to late 19th century; however she did so with great calm and composure. And it must have been pleasing to her husband to know that this very complete and capable woman believed he could do anything, which she did believe. She often commented about a seemingly impossible feat, “Gustavus can do it.” At the same time she carefully protected him from the raucous noise and hurly-burly of a household of boisterous children without in any way hampering the lively brood.

Ann appears to have managed to give her children the feeling that each was special. For Helen it was the hour or two they spent mending—sewing on buttons and darning–on Saturday mornings. “I think the chief charm was the quiet and being with Mother alone,” her daughter remembered.

Helen wrote of how the children were taught about money. “Each child had his savings bank and, when it was filled, Father deposited the contents in a savings account in the bank. From the time that Swift & Company first issued stock, Father saw to it that all the children had an interest in the business. Birthdays and Christmas days, he always brought us two shares of stock. ‘Here,’ he would say, ‘one share is a present. The other share you are to pay for out of your dividends and your savings.’ So we were kept constantly in debt. I suppose he thought it was good training for us…as a large business must be always more or less in debt.” At G. F.’s death—much too early–the Chicago Tribune guessed that $27 million worth of stock—in turn of the 20th century dollars–was held within the little family.

In 1897, Gustavus Swift decided he and his family no longer needed to live next to the stockyards, as they had for 22 years. He purchased a spacious lot at the corner of Ellis Avenue and 49th Street and ground was broken in the spring of 1898.

Gustavus was determined that the new house would completed by Thanksgiving 1898, No one believed it possible but Helen remembered her mother saying, “if Gustavus’ heart is set on it, it will be accomplished,” and it was.

At last! A lovely, formal house in a fine residential neighborhood. However, its owner would enjoy it for a very short time

In March 1903, when he was not quite 64, Gustavus underwent routine gall bladder surgery at home on a Sunday. He convalesced well and was thought be nearly recovered within a few days. On the morning of March 29, ‘’he had appeared in excellent spirits, talking and joking with the members of his family,” as reported in the Chicago Tribune.

However, following a light breakfast, he was lying in bed listening to Ann read poetry to him. He raised himself for a moment, as if to look out a window, fell back and was gone.

It was a massive post-surgery hemorrhage.

The giant of the Yards, a few months before his gall bladder surgery and unexpected death.

Publisher Megan McKinney’s Classic Chicago Dynasties series on the family of Gustavus Swift will continue next with a segment on Louis F. Swift of Lake Forest.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl