By Cheryl Anderson

“I stopped working because of the war. Everyone in my place had someone who was in uniform—a husband, a brother, a father. The House of Chanel was empty two hours after war was declared.”

—Chanel

It was to be the last peacetime summer—that of 1939. It brought out the fun the Riviera was known for: fireworks, balls, open-air concerts, follies, theatres, constant partying and looking forward to the first Cannes Film Festival on September 1. An atmosphere of gaiety prevailed, all in an attempt to hold off the turmoil approaching, and that which was already around them—many on the Riviera not believing war was imminent.

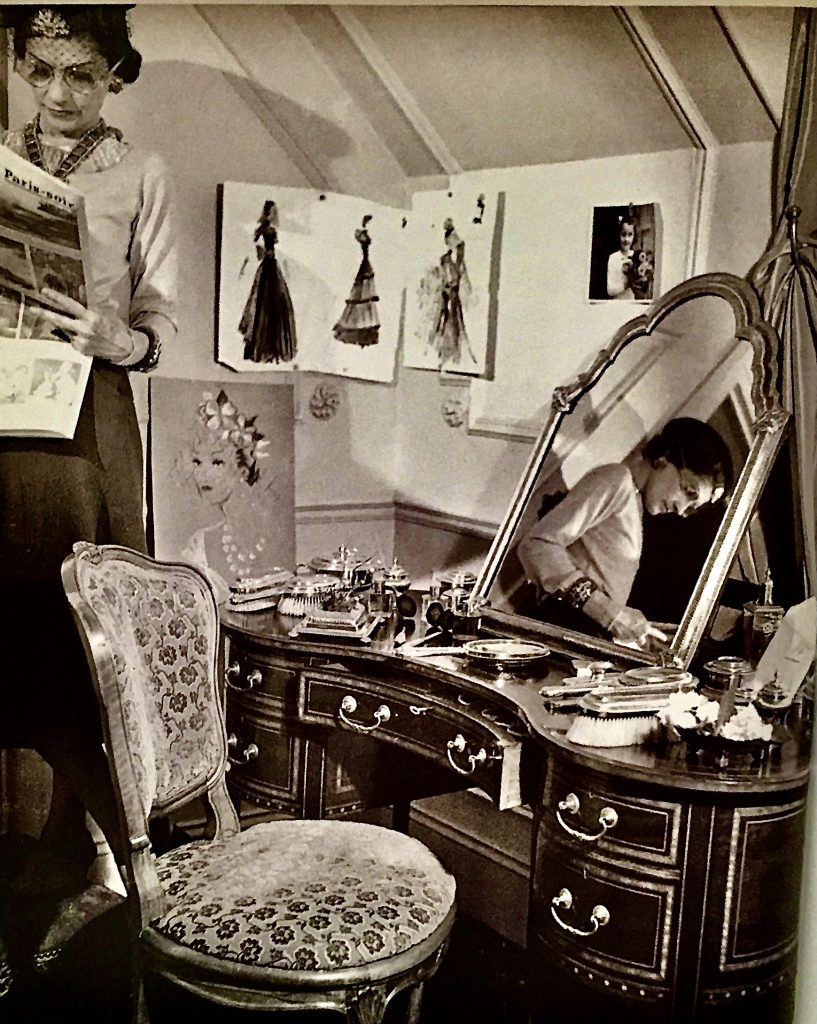

Chanel in her apartment at the Ritz Hotel 1937. Fashion illustrations pinned to the wall.

All the fashionables were on the Riviera that summer—Chanel was at her villa, La Pausa. She had completed her spring collection and the costumes forBaccnanale. Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo was Massine’s ballet company. Salvador Dali designed the ballet and had asked Chanel to design the costumes. Dali met Massine at La Pausa while Madamoiselle was in the midst of working on her 1939 spring collection.

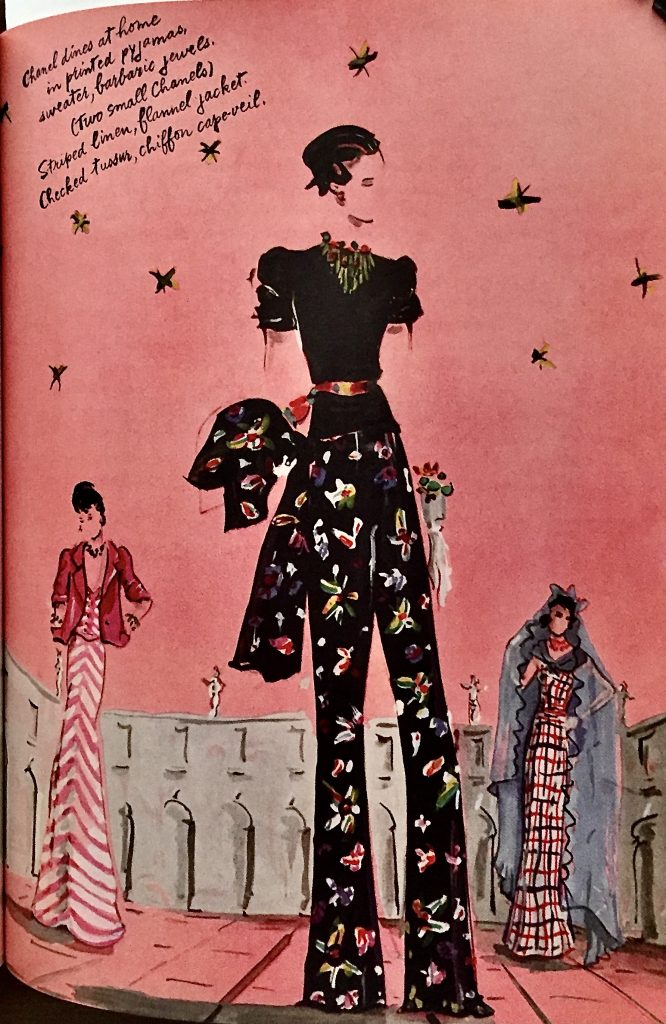

Sketch by Bouché of Chanel gypsy dresses for Vogue 1938.

As late as September 1 when told the Germans had invaded Poland, the Duke of Windsor did not believe it would happen, saying: “Oh, just another sensational report.” At the time, the Windsors were residing at Château de La Croë. He sent a telegram to Hitler pleading for peace: “I address to you my entirely personal simple though earnest appeal for your utmost influence toward the peaceful solution of the present problem.” In response, three days later, Hitler wrote back: “My attitude towards England remains the same.” It would not be the drôle de guerre as some thought.

With the signing of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact on August 23 1939, war was viewed as being for certain—Churchill flew home from the Riviera immediately. Chanel heard about the pact signing and prepared to leave Roquebrune for Paris to work on her next collection. She continued to live in Paris at the Ritz despite Paris being deserted.

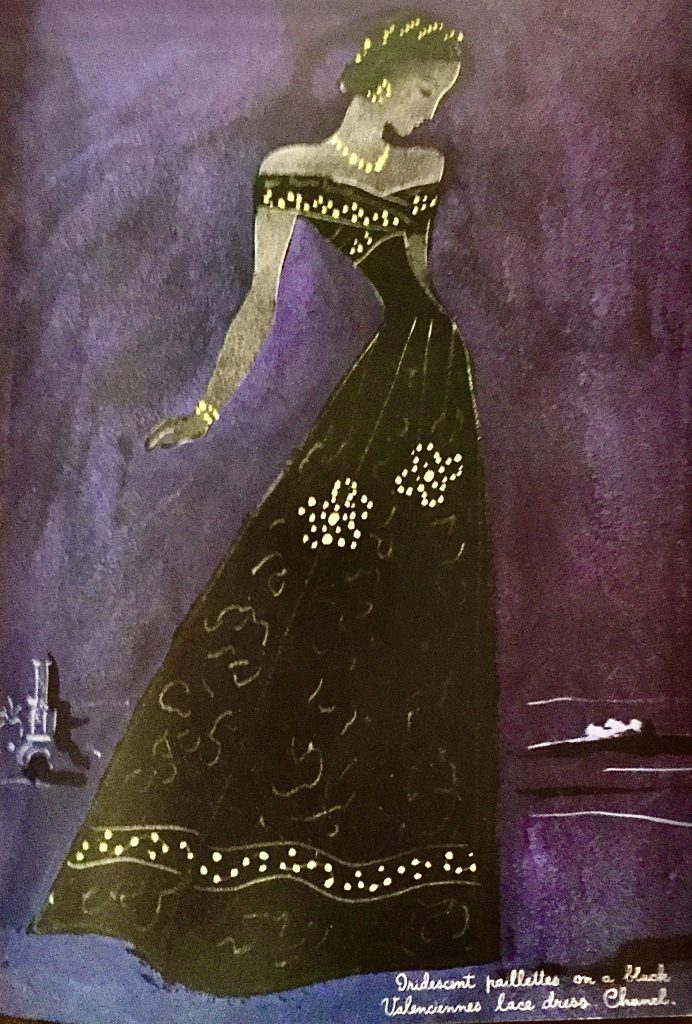

Tricolour evening gown–one of the last evening dresses presented by Chanel before the declaration of war. Sketch by Eric for Vogue 1939.

August 1939, Picasso painted, Night Fishing at Antibes, saying: “I have not painted the war…but I have no doubt the war is in these paintings I have done.” This particular painting is described by some as depicting the end of an era. He and others knew what the signing of the pact meant.

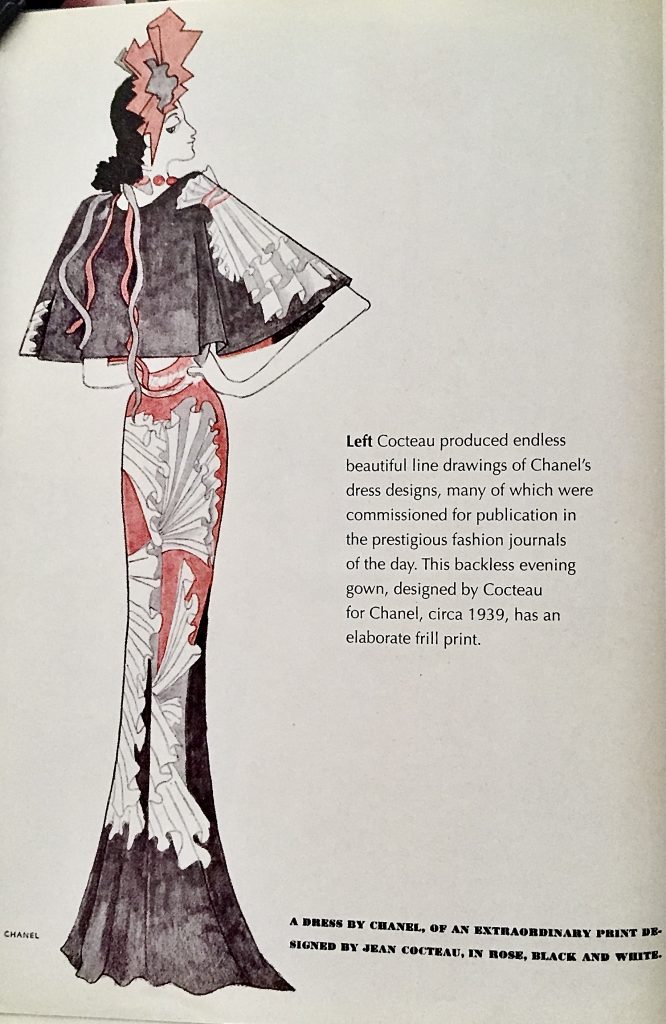

A Jean Cocteau illustration of a Chanel evening gown 1938.

Churchill was staying at the luxurious Château de l’Horizon during the winter 1938-39—not painting as he often did on the Riviera as the light was not good, instead worked on the proofs of his book. Marlene Dietrich decided to get a tan, and approached doing so with, “the same obsessive concentration that she devoted to every aspect of her appearance and image”, says Anne de Courcy. She had a special tanning oil blended: olive oil, iodine and a few drops of red-wine vinegar—tan and beautiful and “noticed” in a white skintight bathing suit. And, once again caught the eye of Joseph Kennedy. During that last summer of 1939, the Kennedy family stayed at the Domaine de Ranguin on the Riviera with its fabulous rose garden. It’s been noted that Rose Kennedy would not let her girls wear two-piece bathing suits that were in vogue that summer—one-piece only.

Records show that Churchill continued to visit Chanel at the Ritz, even after the outbreak of war on September 1, 1939—and on a regular monthly basis before Germany invaded Paris. It’s speculated that Churchill would have known of her plan to close the House of Chanel.

One of the last evening dresses for the 1938-39 collection before the war. Tricolour grosgrain ribbon edges the silk chiffon and grosgrain bodice with a matching silk chiffon skirt.

Cap Ferrat became a military zone with machine-gun emplacements and an anti-aircraft battery. The inveterate party-giver, Elsa Maxwell, gave a party for 200 on the last day of August. Looking across the way, the guests witnessed the blackout ordered by the French government—tanks and panzer divisions had gathered on the Polish border. As her guests stood there, they watched the blackout roll-over Cannes, and below where they were standing saw the lights of Juan-les-Pins and Golfe-Juan disappear and the lights of above Nice fade.

The life the rich on the Riviera had enjoyed was over—the Sporting Club and Casino in Monte Carlo were shut. Cannes Film Festival was canceled—it had been planned for September 1 1939 that turned out to be just two days before Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. Big department store’s luxury items, jewelry, perfume dropped 70 percent. But, balls and parties continued. Chanel attended Lady Mendl’s garden party at Versailles, complete with circus acrobats, clowns, and three elephants—there she conversed with Wallis Simpson, by the Duchess of Windsor [a loyal customer]. Coco dressed as, la belle dame sans merci, at Count Etienne de Beaumont’s last magnificent costume ball.

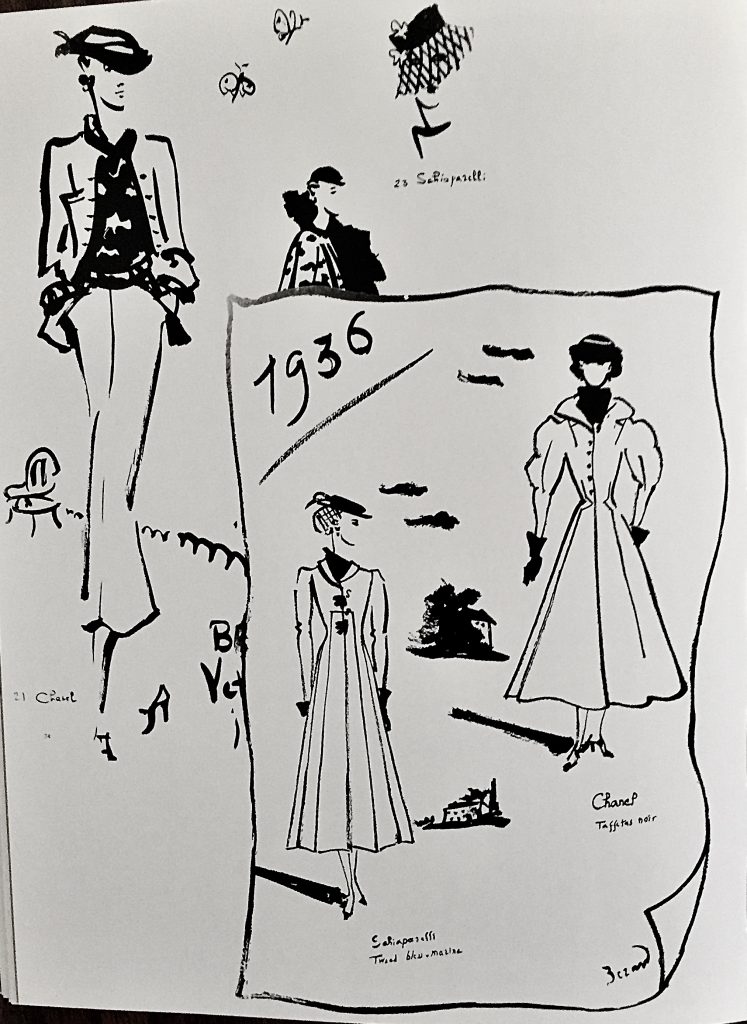

Her style 1937 illustrated by Christian Bérard for American Vogue.

The House of Chanel was closed three weeks after the war began. Many couture houses stayed open per the government’s request to remain open for propaganda purposes. Chanel was unequivocal in her decision to close. The Chanel boutique that sold perfume and accessories stayed open. According to Picardie, “a decision that was to ensure that her property on Rue Cambon was not requisitioned by the Germans after their invasion of Paris.”

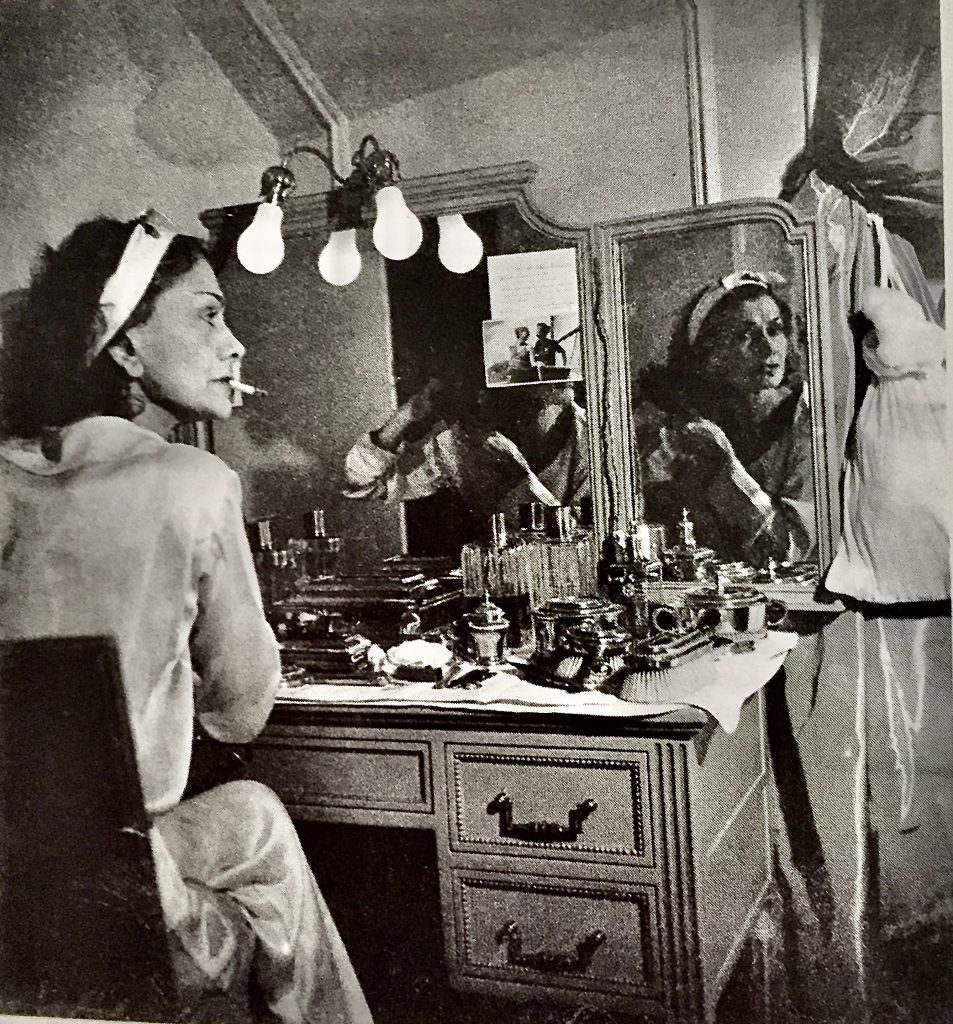

Chanel at her dressing table at the Ritz 1938. Jean Moral |

Chanel at her desk 1938. François Kollar |

Chanel’s closing the House was not about a grudge against the workers that had gone on strike in 1936 or that Schiaparelli was attempting to take her position as a top couturier, as is sometimes posited. In an interview given to her friend, Marcel Haedrich, she stated the simple reason was: “I had the feeling that we had reached the end of an era. And that no one would ever make dresses again. “ Another time saying, “This is no time for fashion.”

Edmonde Charles-Roux declared the thirties, “Chanel’s finest years.”—Chanel remained the doyenne of couturiers even though there was the challenge from “Schiap”, further saying Chanel met her “point for point”. Although, he also said, that the primacy of Chanel was threatened by Schiaparelli, and, “Soon the competition between the two women would become and unremitting vendetta.” Chanel did not suffer any damage from the rivalry—the couturier’s prestige was never higher than in 1938, says Charles-Roux.

Christian Bérard drawings of Chanel and Schiaparelli for Vogue.

To those on the Riviera, life was, as Anne de Courcy puts it: “blue skies, warm seas, pine-scented woods and markets full of fruit, vegetables and fresh fish, the idea of war must have seemed unreal…It was a summer of feverish gaiety, threaded through with rumour and suspicion. There were stories of spies being put ashore at Cap Martin and Cap Ferrat, and rumours about German military-intelligence officers in mufti in the casinos.”

The Spanish Civil War was drawing to a close—officially ending when Franco captured Barcelona on April 1, 1939. People were fleeing Spain. When the French frontier roads opened, 300,000 Spaniards crossed over to the Pyrénées-Orientales sweeping down on the 200,000 French inhabitants. The countryside near the French frontier was littered with the detritus of the refugee’s escape—de Courcy states: “—the Riviera itself was barely conscious of the wretched influx of humanity. That February, Cannes held its annual Fête du Mimosa and Nice its Bataille de Fleiurs, and the spring couture collections were shown as usual.”

In the 1939 spring collection, Chanel had stepped away from the clean lines she was known for with its palette of black, white, beige, and navy-blue in evening wear—et voila, gypsy dresses to dance in. Americans were great fans and foreign artist’s drawings of the gypsy dresses appeared in all the magazines.

“I don’t like people talking about the Chanel fashion, Chanel–above all else, is a style. Fashion, you see, goes out of fashion. Style never.” Coco Chanel Note the signature white collar and cuffs.

Vogue describing it this way: “the provoking gypsy modesty of Chanel’s bodice-and-skirt dresses.” On some of the evening dresses, were le tricolour, red, white, and blue. The English edition of Vogue wrote: “In Paris, le sex-appeal is the principal theme…for daytime the waist was in and well cinched, whereas for evening everything was fire and flames, thanks to the craze for sequins, which proliferated all over bodices, boleros, and skirt bottoms.”

In the words of Edmond Charles-Roux: “But however brilliant the evening dresses, they would have a brief life. Once war had been declared in 1939, all such frippery disappeared. Meanwhile, the neat and attractive daytime wear of that year endured, practically unchanged, throughout the occupation, as if in that triste period fashion wanted to preserve the happy impression of Europe’s last moment of peace.”

Chanel referred to Schiaparelli as, “that Italian woman that makes dresses.” Schiaparelli introduced the color “shocking pink” and other voyant colours— Chanel’s answer to that was the gypsy dress. Emma Baxter-Wright describes Schiaparelli style as: “witty creations, infused with shocking colour and surreal gimmicks, were diametrically opposed to everything Chanel represented.”

“Gypsy dresses, some with lace ruffles on the bodice and as flounces on skirts others with full, crinoline-style overskirts or broderie-anglaise petticoats and ‘the divine brocades, the little boleros, the roses in the hair’ , as recorded by Diana Vreeland for Harper’s Bazaar.” She wore and adored Chanel’s gypsy dresses with, “ ‘the dégagé gypsy skirts, the divine brocades, the little boleros, the roses in the hair.’ ” About Chanel, she said: “I learned everything from Chanel as far as the way I like clothes…She was extraordinary. The alertness of the woman. The charm! You would have fallen in love with her. She was mesmerizing, strange, alarming, witty…You can’t compare anyone with Chanel. They haven’t got the chien! Or the chic. She was French don’t forget—totally French!”

Mademoiselle Gabrielle Chanel 1937.

Vreeland once described her favorite Chanel outfit: “a huge skirt of silver lamé, quilted and weighted in pearls, worn with a linen lace shirt and, over it, a lace bolero encrusted with diamanté and pearls. It was, she said, ‘the most beautiful dress I’ve ever owned.’ ”

Diana’s husband left leaving her in Paris saying, “There’s no point in taking Diana away from Chanel and her shoes.” Diana knew she had to leave and was booked on the Ile de France sailing on September 3 from Le Havre. She remembers September 2: “I’ll never forget that afternoon coming down rue Cambon—my last afternoon in Paris for five years…I’d just had my last fitting at Chanel…I was so depressed—leaving Chanel, leaving Europe, leaving all the world of…my world.”

That evening Diana walked down the Champs-Elysée with a friend. “It would be getting dark at six. The weather was balmy, it was quite crowded with people, and absolutely quiet. I can remember exactly what I had on: a little black moiré tailleur from Chanel, a little piece of black lace wrapped around my head, and beautiful, absolutely exquisite black slippers like kid gloves.” In July, she had described Paris: “jammed with buyers—frantic, amusing, exhausting and glorious.”

A Cocteau design for Chanel couture 1939.

Janet Flanner, for the New Yorker, observing the last few weeks of freedom wrote: “There have been money and music in the air, with people enjoying the first good time since the bad time started in Munich last summer…The expensive hotels have been full of American and English tourists…French workmen are working; France’s exports are up; her trade balance continues to bulge favorably; business is close to having a little boom. It has taken the threat of war to make the French loosen up and have a really swell and civilized good time. The gaiety in Paris has been an important political symptom of something serious and solid, as well as spirited, that is in the air in France today.”

France was invaded in May 1940, the approach to Paris in June. It became obvious that it was necessary to flee Paris. Chanel packed several huge trunks and stored them at the Ritz paying two months’ rent in advance. Her replacement chauffeur, the regular chauffeur had been drafted, advised her that they, Chanel and several employees, should not use her Rolls Royce for the escape, so they used his car. She was among the thousands that fled the capitol. The great exodus had begun.

A Cecil Beaton portrait taken in Chanel’s home, about 1935.

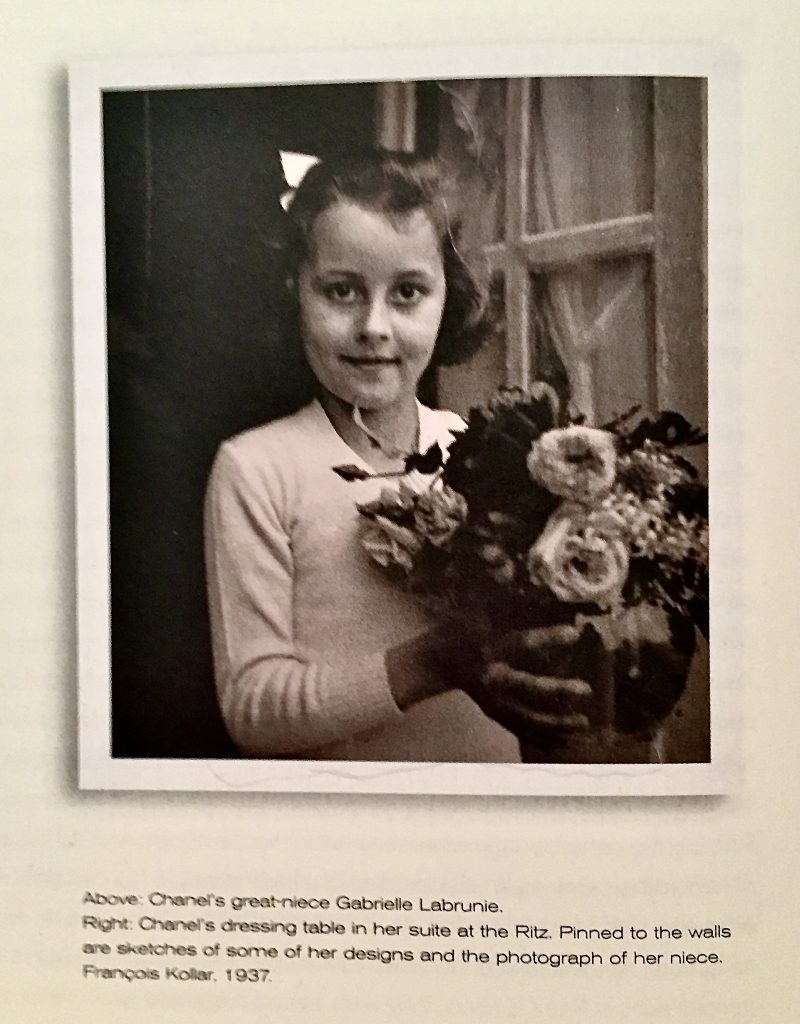

The journey was long and difficult, but they finally made it to the Pyrenees where she had a house that she had bought for her nephew, André Palasse—close to where her former lover, Etienne Balsan, was quietly living in retirement. André was not there, he had joined the French army, but his daughter, Gabrielle, 13 at the time, remembered her aunt’s arrival: “She came in the car with her maid and a few other women—one of them was Madame Aubert [she had been with Coco since their days as seamstresses in Moulin]—so it was quite a job finding places for all of them to stay. Auntie Coco had somehow managed to send on her entire gold dressing table set which had been given to her by my godfather, the Duke of Westminster, and that came to our house separately.” Gabrielle also had a very clear memory of the grief her aunt experienced when she heard the French had surrendered to Germany, saying: “She was already staying with us by the time the Armistice was signed (June 22 1940)—we listened to the news on the radio, and she wept bitterly.”

Closeup of the picture of her great-neice Gabrielle Labrunie on the wall in her dressing room at the Ritz 1937. As an adult, Labrunie was one of the two people closest to Chanel at the end of Chanel’s life.

The summer slowly passed, and as Picardie says: “Chanel fretted to return to Paris.” A complicated plan was conceived with Marie-Louise Bousquet, also staying in the Pyrenees, and the arduous journey back to Paris began. Coco had last seen her at Count Etienne’s costume ball. You may find the story fascinating about her return trip to Paris and their arrival in Paris as recounted in Justine Picardie’s book. They reached Paris in August 1940. The Ritz managed, after much negotiating, to find her a room, but not like the one she had before—this new one was on the top floor of the rue Cambon wing of the building. There was a Nazi-occupied section and a civilian section with separate entrances. There she lived discreetly as wartime shortages were enforced. She was good at improvising—although, she still had her apartment at 31 rue Cambon.

On June 14, 1940, Parisians woke up to a voice with a German accent over a loudspeaker telling them that a curfew was being imposed at 8 pm— German troops rolled into Paris that same evening. The occupation had begun.

The world the privileged had known for so long was at an end, as so many authors and people whose names we are familiar have noted. I wondered, did the gaiety they were basking in have in any way to do with Chanel’s gypsy designs more than merely her competition with Schiaparelli? Chanel often said you have to design for the times in which you are living and at that moment they were all hanging onto what they knew, and hoping that it would never end. Chanel’s 1939 flamboyant spring evening dress collection was such a departure from what she was heretofore known for that, perhaps, Mademoiselle Gabrielle Chanel’s gypsy dresses reflected that hope.

“The Riviera was much more than just an abstraction in the sun, a refuge beyond any century, a small portable theater for the use of the ‘happy few’, nor was it exempt from anxiety and criticism. Behind the masquerades and the parties, in the shade of palms and flowering mimosas, time was running out. “The whole place”, wrote Klaus Mann in New York, at the start of the war, recollecting the landscape of his life, “should include the grim, wan color of danger, and the reflection of approaching fires, and the phosphorescent halo of fate.”

À bientôt