By Milos Stehlik

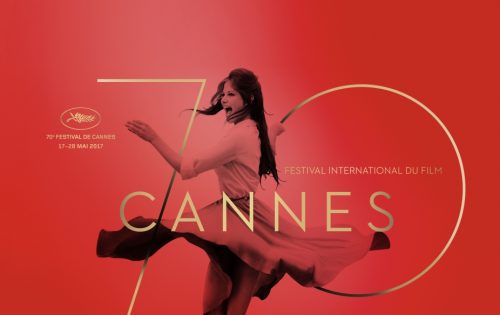

Next month will mark the 30th anniversary of my annual pilgrimage to the Cannes Film Festival.

That being said, Cannes is on my mind. Though I’ve never done it, Cannes is something like space flight. You have to prepare and then let go because the experience is so intense that you can never control it. You can only go with the flow and react as it happens. Seeing five or six films a day for ten days straight is not for the faint-hearted.

The intensity explodes when a movie truly hits its mark. Seeing the world premiere of Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso – a very emotional film about the fragility of cinema – was astonishing. Seeing three thousand other people (the capacity of the Grand Theatre Lumiere where the film was shown) with tears streaming down their faces when the film ended is not an experience to forget. The opposite, too, can be true. Last year at the screening of Sean Penn’s new feature, The Last Face, starring his ex-girlfriend Charlize Theron (they supposedly broke up in Cannes the year before), I sat next to New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis. When the film was finally over, we were both totally stunned by the film’s insipid stupidity. Manohla gave a huge sigh and simply said, “Wow.”

Fortunately, Cannes does offer comic relief. Sometimes this happens in the Cannes awards ceremony. It’s nationally televised live and – unlike the heavily scripted Oscars – often veers off course. Last year, no one could figure out just how to shut up director Houda Benyamina who received the Camera d’Or (for best first feature) and get her off stage as she went on and on. Some years ago, every other word from the mouth of actress Sophie Marceau was, “merde” – the films were “merde,” Cannes was “merde,” the weather was “merde” and so on.

Sometimes, ignorance is just wonderful. Even though I know just how cynical the film world can be, I was disillusioned when I realized that I had just seen Jeanne Moreau ascending the red carpeted staircase to the Palais Festivals for a screening. ‘Just because she was going up the red carpet doesn’t mean she was going to actually stay and watch the movie,’ I was corrected. Many of the stars just go up the stairs to be seen and then escape through a side door and rarely stay to watch the movie. No very, very slow 4-hour Filipino movies for them.

I saw one such escape while walking down the interior center stairs of the Palais. Suddenly there was a surging huge crowd; people packed together, shoving, pushing, and slowly moving out of the side theatre entrance towards the stairs. It was impossible to see what all the commotion was about, except that in the center of the sea of black, there was a blonde head with a garland of white flowers. It made no sense. Then suddenly, the crowd parted for a moment and through the crack I saw Cicciolina, (real name, Ilona Staller), a porn star, once the wife of artist Jeff Koons, and eventually a member of the Italian parliament. With the exception of the garland on her head, she was stark naked.

The pleasant or relaxing moments are not so many since everyone is always rushed and exhausted, but one such gentle moment was during the screening of Steven Soderbergh’s two-part film (which he now says he regrets having made) Che, the subject being Che Guevara. The producers generously gave out sandwiches in paper bags in the intermission between the two-hour parts of the film.

The French are very good at pomp and circumstance. Though I no longer remember which movie occasioned this, I do recall a special detail of the French police or military in Napoleonic dress, poised with their swords on the steps to the Palais. Or does my memory play tricks? There was also some historic Russian film for which the Russian producer closed down the Croisette – the street bordering the Mediterranean and the Palais which is always impossibly congested – and had a parade of soldiers (or hired actors– who could tell?) on horseback, in similar historic dress. They minted special coins for the occasion and gave them to passersby – kind of like the Russian czar visiting the muzhiks on a distant estate and doling out alms.

Despite the circus of Cannes, the contradiction is that Cannes is really about one thing: film. Movies can be high profile, star-driven vehicles. But the genius of the Cannes Film Festival is that it can put films without stars on a world stage — films for which it is a pre-eminent global launching pad.

Last year’s Romanian film, Graduation, (just now opening in Chicago) is a quiet and totally brilliant film about compromise, corruption and complicity, and is just as intense as the best thriller. But it’s without stars recognizable to Americans, and it is a film for adults, not pre-pubescent teenagers. A good example is also Ousmane Sembene’s last film, Moolade. The last feature by this great African filmmaker is a powerful call to arms and a stirring tribute to the power of women.

Sembene, who was Senegalese, fought against near-impossible odds to make films in Africa, where the film industry was mostly non-existent. Emigrating from Senegal to France, he first worked as a dock worker – carrying heavy sacks and loading ships. Then he hurt his back and began writing. He wrote a novel, Black Girl, about the experiences of an African servant girl in France. He wanted to turn the novel into a film, but since no European film school would accept him, he went to film school in Moscow, learned filmmaking, and turned his novel into a film.

Moolade is set in a village in Burkina Faso. Its protagonist, Colle, is the second of her husband’s three wives. When four young girls face undergoing ritual genital circumcision, they flee to Colle’s household for protection. Colle, who has successfully shielded her own daughter from mutilation, invokes the custom of “moolade,” (sanctuary) to protect the girls. Without giving away the entire plot, the film dramatizes the bravery of the village women as they rise up against the village traditionalists and against the “purification” ritual. It all sounds very dark and tragic, but the film is, in fact, exhilarating and empowering because here are characters who are “real” people, who, when they come together, can create change.

This is why film is so powerful: would there have been such an outcry against how United Airlines treated a passenger if two people had not captured his “removal” from the airplane on their cellphones? Would the president’s press secretary have apologized as much for his (at best) insensitive comparison to Hitler’s poison gas if there had been no cameras present?

It’s the moving image which shapes our attitudes and is the most powerful element in writing our history.

(Editor’s Note: Milos Stehlik is the Founder and Artistic Director of Facets which for 41 years has harnessed the power of film to change lives and thus change the world. Meet Milos at the Facets Screen Gems Gala May 3 at the Arts Club. Marjorie Craig Benton and Judy and Mickey Gaynor chair the benefit honoring civil rights advocate Doris Conant. Proceeds support year-round educational programs at Facets and the Chicago International Children’s Film Festival, the most celebrated children’s film festival in North America.

For further information call 773-281-9075, ext. 3052 or visit facets.org)