By Megan McKinney

Ben Hecht was Hollywood’s greatest screen writer. It was not an occupation he respected or enjoyed, but he did respect and enjoy the money—the industry’s highest compensation “for work that required no more effort than a game of pinochle.” Each year he would journey out to California at the beginning of January with his wife, oil paintings, servants and records. He would stay exactly as long as it took to earn enough money to live expensively for the rest of the year, then it was straight back to New York.

Hollywood treated Hecht well in every way. It presented him with its first Best Original Story Academy Award back in 1927 for Josef von Sternberg’s Underworld. Ben’s tale of two Chicago gangsters (pre-Code, as you can see from the publicity still) was a huge hit and it set the tone for gangster films of the next nine-plus decades. Hecht knew a lot about Chicago gangsters; quite a lot. And it was Chicago, with its rough early 20th century newspaper world and accompanying low life that Hecht remembered fondly throughout the rest of his days.

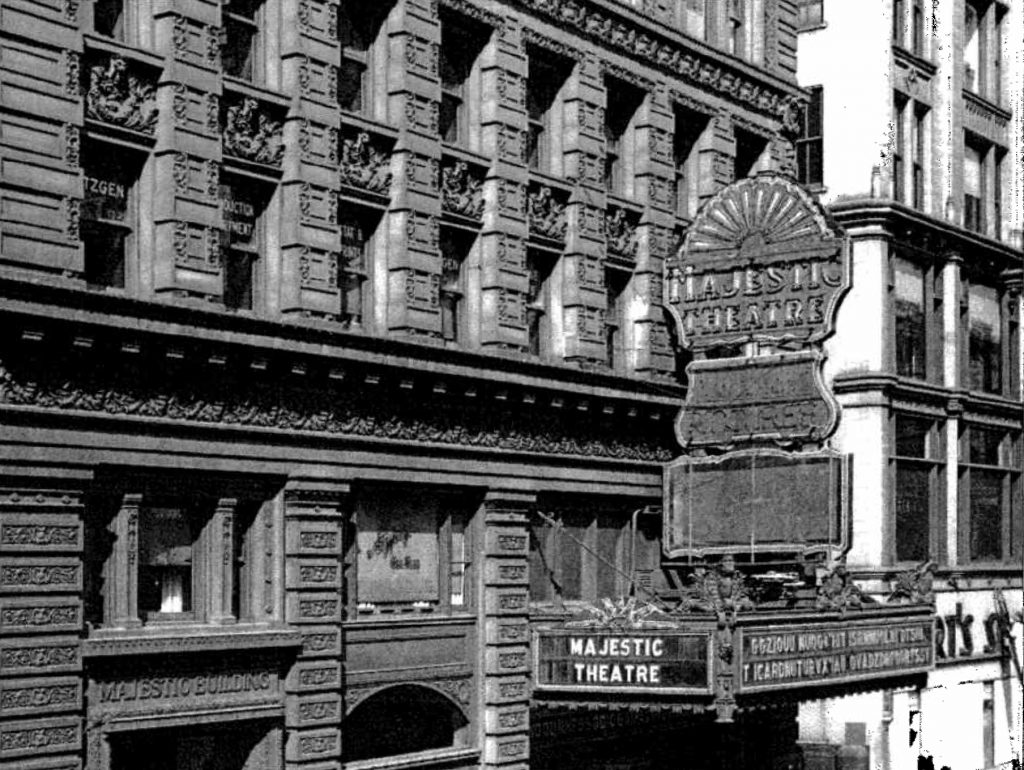

It had all begun on July 3, 1910 while 16-year-old Bennie Hecht was standing in line to see a vaudeville show at the Majestic Theatre, 22 West Monroe St. He had run away from Wisconsin the previous day, not from his Racine home, but from Madison, where he had been a student for three days before deciding university life was not for him.

He was buying a vaudeville ticket at the Majestic box office when he heard a voice cry out his name. It was a man who identified himself as Bennie’s uncle and then asked, “What are you doing here?”

“I’m looking for a job,” the boy lied.

It turned out the uncle was a liquor salesman, who was on his way to call on one of his “best customers” (did you guess newspaper man?) and if 16-year-old Bennie came with along him there just might be a job in it for the boy.

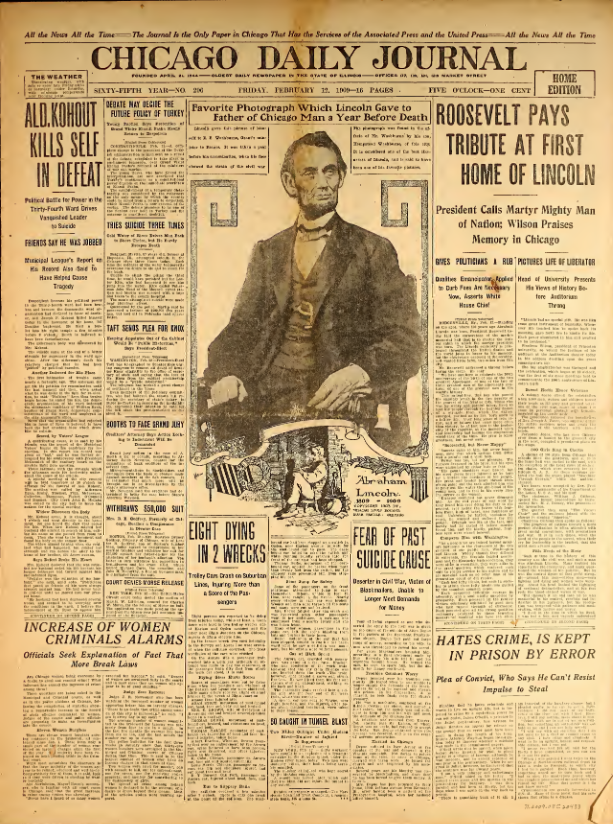

One of the uncle’s “best customers” turned out to be John C. Eastman, who was owner and publisher of the venerable Chicago Daily Journal, Illinois’ oldest daily newspaper. If Bennie could write a poem about a bull who swallows a bumblebee, promised Mr. Eastman, and add a naughty moral to it, there would be a newspaper job for the 16-year-old college dropout.

The job paid $12.50 a week—remember, this was 1910—and the position was “picture chaser”. In Hecht’s words, he was “sent forth each dawn to fetch back photograph of…a woman who had undergone some unusual experience during the night, such as rape, suicide or murder.” Families of such women were understandably protective, and photographs were almost impossible to obtain. Hecht wrote that his technique was to go to the scene of the “experience” and “hover broodingly outside the ring of interviewers. I learned early not to ask for what I wanted. Instead, I scurried through bedrooms, poked noiselessly into closets, trunks and bureau drawers, and–the coveted photograph under my coat–bolted for the street.”

Hecht performed so well as a picture chaser, his salary crept up to a weekly $15 and soon he was a bono fide Chicago Daily Journal reporter.

Portraying the young newsroom Hecht is Cary Grant in a role taken from a great Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur screenplay. But we’ll get to that later.

Eventually, Ben entered the Chicago newspaper big time, was recruited by Chicago Daily News Editor Henry Justin Smith and became a “tough crime reporter,” as well as a figure in Chicago literary circles. From 1918 to 1919, he served as war correspondent in Berlin for the Daily News and, in 1921, inaugurated an enormously influential column, A Thousand and One Afternoons in Chicago. A century later the column has become a book.

The world remembers Hecht not as a newspaperman but for his screenplays, which included some of Classic Chicago readers’ best-loved films. He and a favorite collaborator, Charles MacArthur, for example, wrote the scenario for 1939’s Wuthering Heights.

“We wrote plays and movies together,” wrote Hecht of MacArthur in his autobiography, A Child of the Century. “But our literary work was only a sideline of our relationship. Our friendship was founded on a mutual obsession. We were both obsessed with our youthful years. I had no more interest in Charlie’s past than he had in mine. But for twenty-five years we assisted each other in behaving as if these pasts had never vanished. We remained newspaper reporters and continued to keep our hats on before the boss, drop ashes on the floor and distain all practical people.”

“But it is difficult,” Hecht continued, writing about MacArthur, above left, “for two grown men to continue playing games and palavering as if they were marking time in some pressroom. Thus, since MacArthur (the non-reporter) was hotly in love with the theater and I was ready to work on anything, we added playwriting to our relationship and later movie writing.”

Hecht was also the unaccredited script doctor for Gone With The Wind. But his greatest success, another mega-hit with MacArthur, was The Front Page, first as a 1928 Broadway smash and then many times as a successful film.

The first film version in 1931, which created a blueprint for all future newspaper films, starred dapper Adolphe Menjou as Walter Burns, who Hecht and MacArthur created from the real-life Chicago newspaper editor, Walter Howey, with Pat O’Brien in the Hildy Johnson role.

It’s quite a movie. The entire Chicago death row press corps is squeezed into a tiny set–allegedly the Criminal Courts Building press room–which must have made the Broadway stage for the 1928 play preceding it seem spacious. It was rougher still for the actor playing the condemned man, who spends nearly the whole of the evening hidden behind the tightly shut wooden roll of a roll-top desk.

Many people’s favorite Front Page adaptation is His Girl Friday, where Cary Grant shows up again as Walter Burns. In this version, Hildy Johnson is played by a woman, Rosalind Russell.

Ben Hecht’s stories about his life in Chicago, Hollywood, New York or anywhere else usually have a bit of far-fetched movie scenario about them. Perhaps, as Norman Mailer noted in 1973, it’s because Hecht “was never a writer to tell the truth when a concoction could put life in his prose.” But think of the fun he has given us!

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl