By Francesco Bianchini

Someday I will write my memoirs and talk about the many houses – infested by mice, inhabited by bats, wet and neglected, sore in spirit and physique, mistreated, squeezed like lemons – and the part I’ve always had in taking charge of theirs needs, and to their appeals otherwise unheard. It’s clear that homes in good health and dazzling shape have not taken a hold on me, while those – perhaps of noble birth but fatally fallen – exert an irresistible appeal. In my vision, instead of filthy and lackluster floors, I see expanses of shiny tiles, scented with beeswax. I imagine surfaces that invite one to touch, not recoil from moldy and moth-eaten furniture; there are immaculate and well-stocked kitchens where now there is nothing but soot and grime. I am not so short-sighted to not recognize that life has served me magnificent opportunities, although some of them on the tin and dented platters.

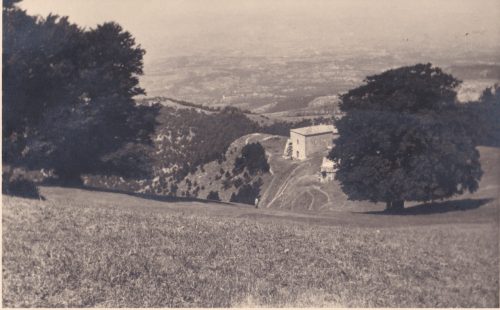

In this spirit, as well as celebrating the end of lockdown and fleeing the shipwreck of our tourist season, Dan and I decided to return to San Pietro, the family property at the top of the Umbrian Apennines where I spent my summers as a child. Little was left of the abbey at the time of my great-grandfather’s purchase, nothing but a pile of stones on a spur of rock, but overlooking the entire middle Tiber valley from our mountains to those of Tuscany and Lazio. Sepia photos record the abbey in all its exotic antiquity, as in a Piranese engraving, its windows like the empty sockets of a mummified skull; stones crumbling and suffocated by weeds. In this condition, San Pietro survived for seven hundred years after a fire dispersed its last occupants, a small community of Cluniac monks.

San Pietro, about twenty years after my great-grandfather’s 1904 purchase and complete renovation

I’ve actually kept dating San Pietro over the years, spending periods in solitude or testing the endurance of friends and companions. In every season the arrival there is followed by the same rituals: one pushes open the door of the former guardian’s cottage, swollen by humidity, and is hit by the smell of dry leaves, mold, and cold ashes. You go to the belvedere hunting for pine cones and kindling, and climb the slope, along the edge of the woods to collect fallen branches to light a good fire. Afterward, doors and windows of the abbey must be thrown open to air it out. The paved floor will be swept, the butts of wax candles replaced by dozens of new ones, and the fire will be stoked, water drawn to drink and cook, and – finally! – one can relax and contemplate the work done.

The new generation, me with friends and family, Ferragosto 1986

But after six years of absence, it was me for once who was severely tested. The first bad surprise came before our arrival. The generator was broken and needed to be replaced as soon as possible if we were to have running water in the house, hot water in the morning, a minimum to run the refrigerator, and recharge our computers and phones. The entry drive, five kilometers of dirt with no shoulders or guardrails, and full of exposed bends had been damaged in multiple places by bad weather in recent years. The three monumental beech trees on the crest of the mountain – planted at the time Magellan embarked on his circumnavigation of the globe – had been struck by lightning. The huge trees isolated on the grassy slope – iconic images whose branches spread almost as if to shake hands – appeared forever disfigured. When Dan and I opened the door of the cottage, which we approached cautiously because of the tall grass, we were overwhelmed by a sense of pervasive coldness and rot, the kind with an impenetrable crust. The fireplace looked so derelict as to negate the very idea of its function, and everything looked bleak and covered with a patina of wet and fungous dust.

I abandoned Dan to the first reclamation operations, and trekked disconsolately up the slope, which the morning’s slanting rays were caressing in golden blond. For over a century my family had come here to enjoy the view of the valley, the good air, the excellent spring water so good for the teeth, the priceless quiet. Family photos tell the story: in my great-grandfather’s day, Austrian POWs he’d housed during World War I posing under the beeches in their uniforms, pausing in their work of reforestation. Girls in fresh summer frocks flowered hats and turbans, and armed with binoculars and walking sticks; young men in shorts and hiking shoes, standing in groups on the side of the hill with the abbey ruins in the background. And women laughing from under their parasols and big hats, while tanned men in sporting clothes, wearing boots, and carrying hunting rifles, saunter past. Older chaperones admonishing children to stop fidgeting in front of the lens, while cows, horses, mules, sheep, and dogs wander in the background. And now all I wanted to do was walk away!

Summer idyll before WW1, grandfather Giuseppe and his family camping among the ruins

Austrian POWs under one of the monumental beach trees, circa 1915

The hunting party, circa 1927

Cleaning lasted a week, as in Genesis. On the first day, we separated the good from the bad and filled four giant leaf bags with garbage. On the second day, we tamed the vegetation back within its boundaries, and on the third day, we polished everything in the house so that sunlight would gleam on surfaces again. And so it went, day by day until the work was completed. The plank floors sparkled with beeswax, the copper pots and pans glistened in the candlelight, every kitchen drawer and shelf was emptied and sanitized, every item washed carefully and stored away.

On the seventh day, we rested and contemplated the work done. It was then that Quinto, the old caretaker Ascenzio’s son, now also an old man, dropped by. He brought us a basket of mushrooms he’d picked under the shadow of the beech trees. There were large ones with brown caps, and smaller rounded ones, bright white in color. Torini, they call them – but the name tends to vary from place to place. (Prataioli, I think is the official name.) we removed the clumps of dirt and cut them into pieces. They simmered in a pan on the woodstove with garlic and a pinch or two of the wild mint that flourishes at San Pietro. We served them with spaghetti that night, licking our poor bruised and scratched fingertips.

Quinto’s simple gift |

7th night dinner… |