By Francesco Bianchini

I have mentioned Rodolfo so often that I feel I must dedicate a brief portrait to him. A constant presence in my first thirty years, he entered the family as a valet when my father was still a young gentleman. Rodolfo, therefore, had no official duties in the kitchen, yet he later occupied that post vacated by the excellent cooks who succeeded one another in the house. To him, the kitchen was, for the most part, an ideal place to gather information and combine it with whatever he managed to overhear by lurking near the telephone or behind doors.

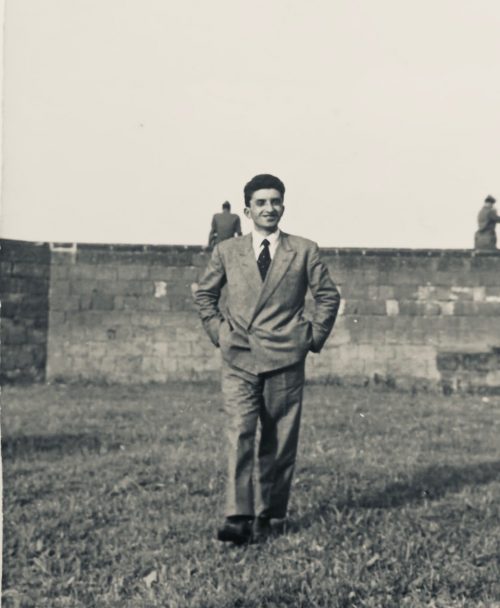

Young and dapper Rodolfo

Despite having no training, Rodolfo was duly credited with an intuitive skill in the preparation of roast beef, and in frying food. Make the roast you do so well, my mother would tell him when she ran out of ideas for a last-minute lunch. And Rodolfo would sizzle the meat in a nice caramelized gravy and place it proudly on the table. When I think of Rodolfo’s fried food, I picture his huge black frying pan, one with a very long handle, and also the conical iron plate with a hole in the center where he’d deposit the fritture to drain when he removed it from the boiling oil. He cut the potatoes into thin disks with a result inevitably not homogeneous; some of them stuck to each other and were soft in the center, others came out as crispy and golden as small suns and sometimes disappeared – plundered from the draining dish – before arriving at the table.

Patatine fritte sottili fatte in casa

In his last years of service, Rodolfo found himself alone in the kitchen. There were no longer the cabals, the subterfuges, the chatter, the scenes that had so tickled him. He fell into a depression and started drinking. Of course, he would never have dreamed of being caught with a glass in his hand, but as you passed through the kitchen – especially during the empty afternoon hours – you could hear the unmistakable tinkling of the crystal stopper on the decanter in the pantry. After that, Rodolfo would become whiny and pathetic, and was capable of anything. He would let the pasta cook for a good half hour and serve it all gooey, floating in nothing more than a watery tomato sauce. Or he’d miscalculate the portions and arrive with a tureen full to overflowing when there was only a handful of us at the table. He wandered around the house predicting doom and gloom because his points of reference – the family, our household, our small world – had lost the polish with which he had always embellished them. He took a gloomy and mortifying pleasure in this as if understanding that everything was falling apart around him, which made him feel less inadequate in his own realm.

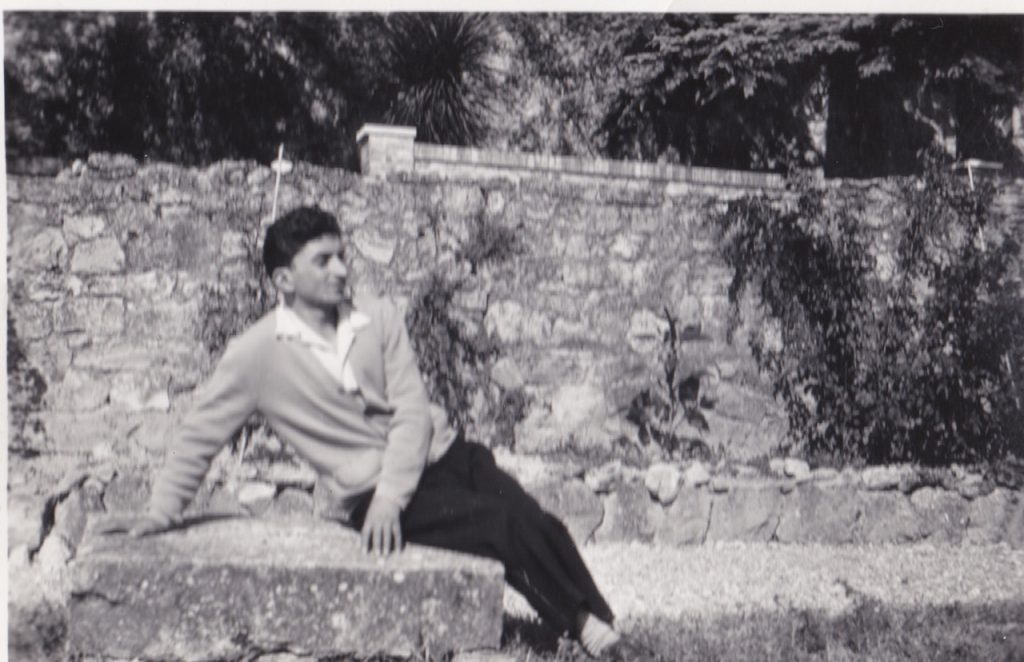

Ever the languid poser

There had never been good blood between Rodolfo and my grandmother Margherita perhaps because each recognized in the other a particular demon of their own. Granny spent long periods of time in our house when she wasn’t visiting her other grandchildren – they were, she intoned, better behaved than us, more talented, more glamorous. To emphasize this disparity, when she came to stay with us she indulged in small but significant sloppiness. For example, a particular pair of shoes had become so loose that their toes hit the ground first, then their heels, in rapid succession as she traversed, to and fro, the terracotta floors. Since she and Rodolfo circled one another for most of the day, spying on each other, Rodolfo was exasperated by that constant clicking. One day he exclaimed, rolling his red eyes, that he was ready to burn those damn shoes! We children liked the idea so much that, taking advantage of our grandmother’s absence, we snatched the infamous shoes from her room and – against Rodolfo’s loud protests, as he never had the courage of his own convictions – threw them into the fireplace. I remember how fascinated we all were to watch them curl up like oriental slippers, enveloped in flames.

Nonna Margherita and some of her less accomplished grandchildren

It is not my intention to paint a negative image of Rodolfo. He was a person who loved to give, although not unconditionally. During my disadvantaged youth, he often slipped five or ten thousand liras into my pocket. Money could not remain in his hands without him feeling the urge to share it with magnificence and liberality. Unfortunately, like one of those grotesque and cursed characters of Dostoevsky, good and evil in the form of primordial instincts within him, were in a perpetual struggle. He was, in fact, one of those people inclined to do good but, as Henry James put it, he did good badly. Yet Rodolfo was a fine connoisseur of the human soul and instinctively found in each one of us the cracks, the weaknesses, on which he was able to leverage.

Rodolfo was an avid collector of things that otherwise would have ended up who knows where. After he retired, I visited him a few times in his bachelor house that he had set up as a small museum – a bit like a superannuated general surrounds himself with the touching objects that chronicle his brilliant career. I would skim, pick up, sniff the trinkets that took me back to faded memories of aunts, the forgotten nooks and crannies of home, apartments in Rome, people dead and buried. Feeling close to the end, of which he was so afraid, Rodolfo begged me to keep this or that object in his memory.

Memory of Rodolfo: a Deruta faience plate he gave me

I saw Rodolfo for the last time at my brother Fabrizio’s wedding. He was wearing a tailcoat, the assembly of which had kept him busy during the previous months. He sat on a small armchair in a languid pose, surrounded by those people for whom he had been an institution for decades. I thought of him wrinkled, shrunken, his highly polished shoes barely touching the ground.