There was Esquire

Esquire’s Petty Girl.

By Megan McKinney

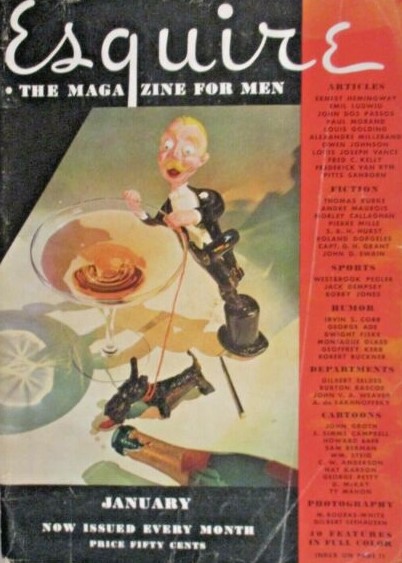

Esquire, one of the greatest American consumer magazines—ever—was created in Chicago in the middle of the Great Depression.

Twenty years before the appearance of Playboy, Esquire shot up to its position as one of the nation’s most widely read publications in the first issue. Immediately and thereafter, its excellence was the envy of Madison Avenue’s most astute magazine pros.

Classic Chicago readers know of David and Alfred Smart, the brothers in whose name the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago was endowed. But do they know it was a Smart brother who founded the historic Esquire?

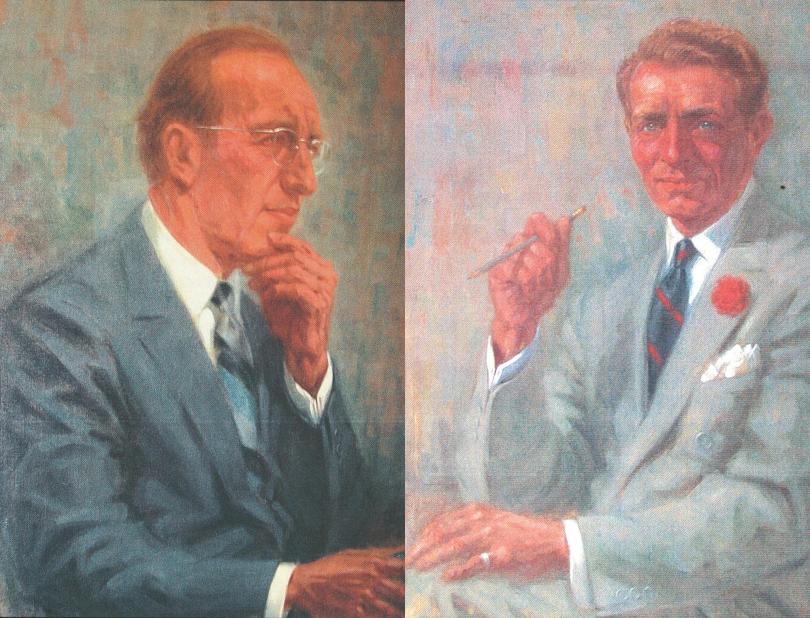

The Smarts, David, above, and Alfred.

Dave Smart teamed up with a brilliant copy writer, Arnold Gingrich, who wrote in “Broad-A English,” which Dave felt would add “class” to his publication. It was a brave move to launch anything in 1933, but this would be a publication tapping a market for male fashion and culture at a time when much of the projected market was perceived as selling apples on city street corners. Furthermore, as a later editor, Phillip Moffitt, wrote, the new magazine “required a circulation of 100,000 in order to break even at a cost of fifty cents a copy—this at a time when The Saturday Evening Post sold for a nickel and the combined circulation of Town & Country, Vanity Fair and American Mercury barely came to 100,000. ”

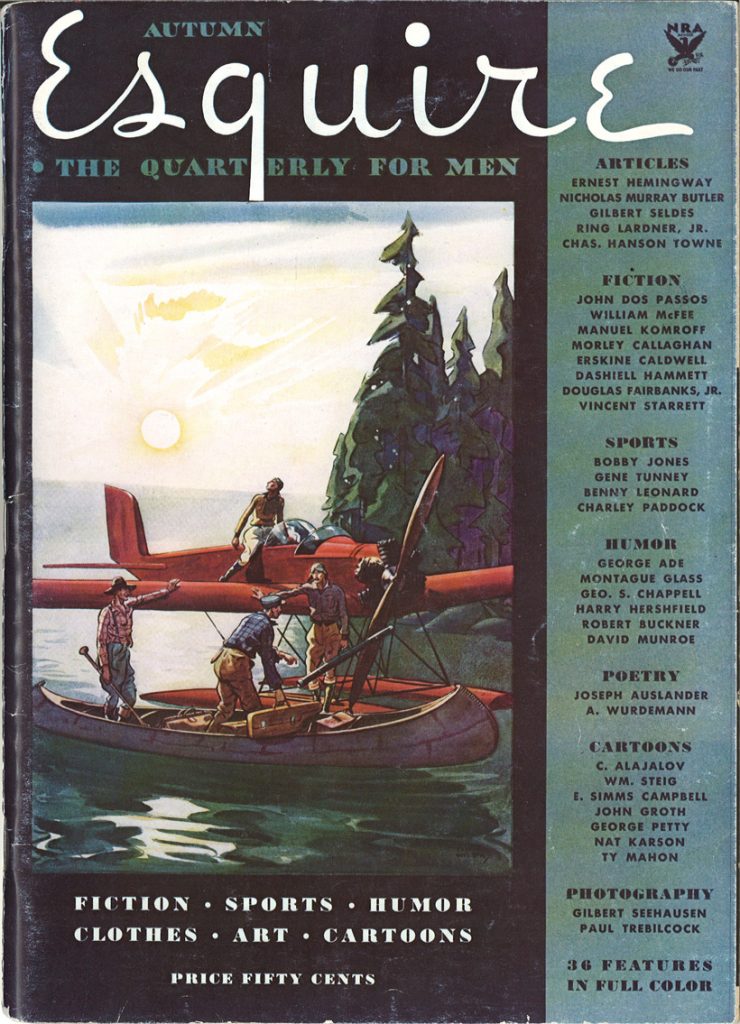

Take a good look along the right margin to see what was being offered in the first issue of Esquire: The Quarterly for Men. For those who had 50 cents to spare, it was a Who’s Who of writers, illustrators, cartoonists, photographers and sports figures, with a film superstar thrown in.

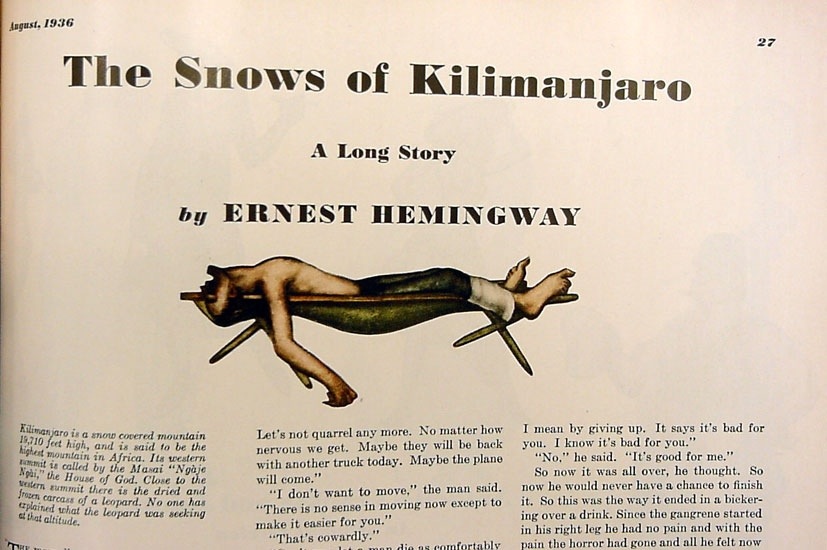

Everybody received a $100 fee—except Ernest Hemingway, who would write a “letter,” each month–if he were paid double what the other writers were receiving. Then, three years into the project Papa didn’t have time to write the August 1936 letter, so he sent in a short story he’d just completed—the masterpiece “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” Quite a $200 bargain for Gingrich and Smart!

Did we mention that the 100,000 copy first issue, at 50 cents each, sold out? Below is the second issue, January 1934, every bit as battered as it should be, with the announcement that Esquire would now be a monthly.

Esquire had quickly adopted its symbol, Esky, a dapper old gentleman with a top hat and popping eyes. Created by artist E. Simms Campbell and Sam Berman, Esky would be around for decades.

The magazine had a few great years with the dapper Arnold Gingrich in the editor’s chair and Henry L. Jackson overseeing the publication’s lengthy fashion section, then it fell off about the time prosperity returned.

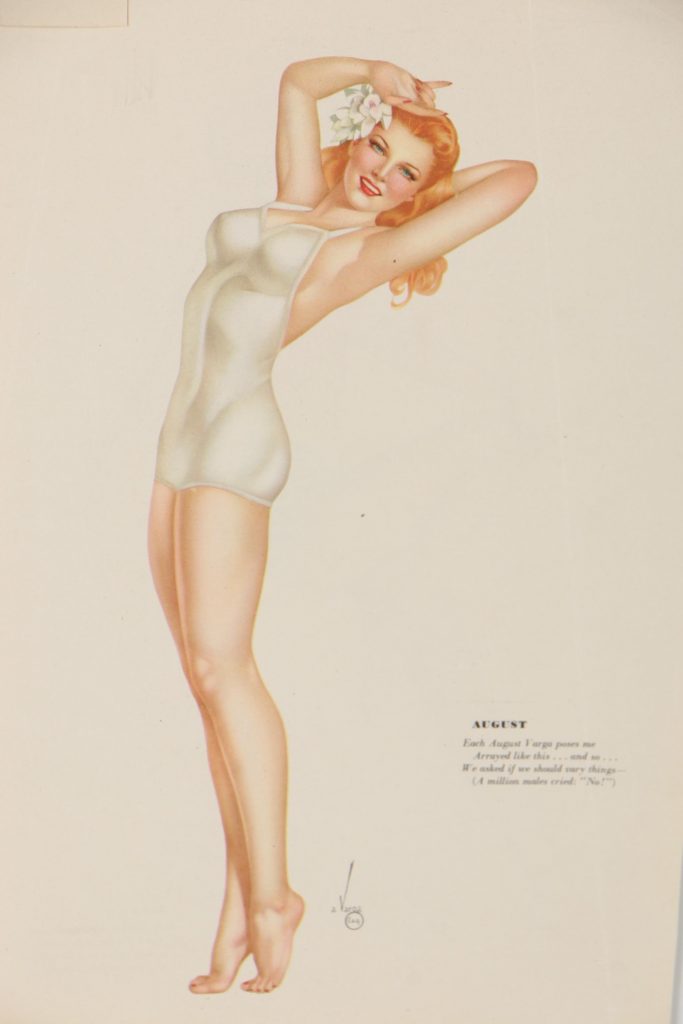

During World War II, Esquire was re-designed to boost the morale of American GI’s, and the Petty Girl was joined by the Vargas Girl.

This was about the time a young Hugh Hefner, who was trying his hand at becoming a cartoonist, worked in promotions at Esquire while developing the idea for a magazine of his own. Hef would later hire the Peruvian Alberto Vargas to contribute his “Girls” to Playboy.

The brothers Al, left, and Dave additionally developed the pocket-size magazine Coronet, also a success. And their Coronet Films was a leading producer and distributor of many documentary short subject movies shown in American public schools from the 1940’s through the 1980’s.

Esquire aficionados recall particularly the magazine’s legendary Harold Hayes era of the 1960’s and 70’s, during the New Journalism movement, when every mid-century print star had at least some association with the magazine. Nearly nine decades after its Chicago launch, Esquire is owned by the Hearst Corporation, which publishes more than 20 editions of the magazine internationally.

Tom Holland on the March 2021 Esquire cover.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo by Robert F. Carl