By Francesco Bianchini

I want to add my voice to the universal, full-throated chorus of readers of Marcel Proust on the 150th anniversary of his birth. Those who have read the entirety of his most famous novel, and also those who have only tried, know that it is not easy. Not so much for the burden of the undertaking, but also – and above all – for the syzygy required between each reader and Proust himself. Unique and magical is the moment when our sensibility is in tune with the author.

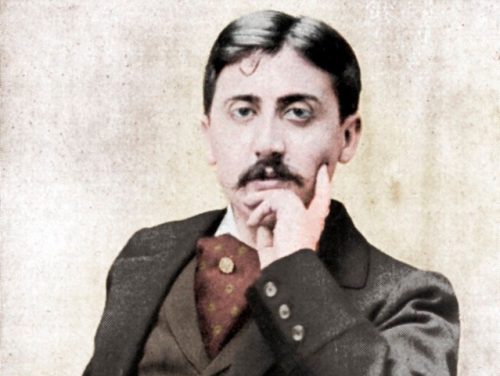

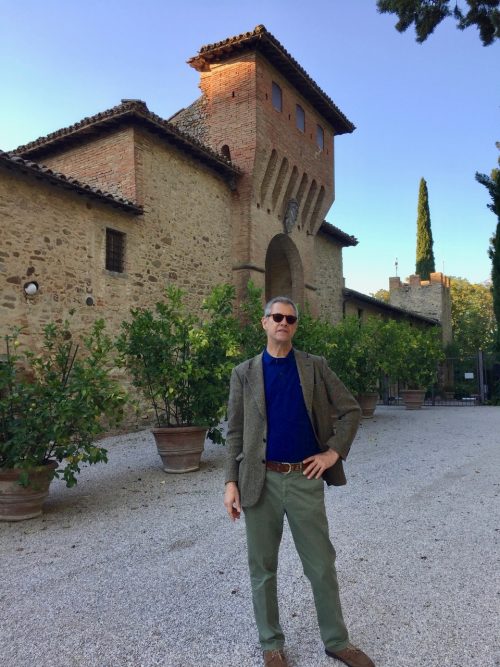

Marcel Proust (1871-1922)

I was barely twenty when my mother gave me the French Gallimard paperback edition in eight volumes – all rather plump – hoping to entice me to read it. I admired them, lined up on my bookshelf; I took them one at a time, considered the ugly drawings from the 1970s that illustrated the covers, thumbed through, and sniffed the pages. As if for a huge mansion, I pushed open the front door to get a feel for it by judging from the vestibule. The opening sentence intrigued me: For a long time, I used to go to bed early. But after that, I got lost in all the objects and people the narrator drowsily conjured in his sleep. Several times I put the first volume – Du côté de chez Swann – in my suitcase with the idea that travel rather than stasis would encourage the project. I took it with me to Bermuda. Those pages, glued tightly to the vicious spine, became filled with the pink sand grains of that island’s beautiful beaches.

Swann’s Way through Ajat

To satisfy my fetishistic relationship with the book, I paid the price of buying the Pléiade edition, in red morocco leather – three volumes printed on fine India paper – and I got rid of the paperbacks. More years went by. By now I’d gotten into the habit with Dan of reading something aloud every night. We enjoyed some classics of English literature that way. Proust came to mind because a mutual American friend had tackled him in a reading group. I then procured a twelve-volume, postwar edition in the translation by Scott Moncrieff – a contemporary of Proust – and with the evocative English title, borrowed from a Shakespeare sonnet, Remembrance of Things Past.

In the spring of 2012, in the kitchen of our farmhouse in Dordogne, sometimes on the porch overlooking our forest of oak and chestnut trees, we began our reading that continued with slowness (due to my long absences during the fall and spring semesters) throughout 2013 and 2014 – the latter years as we moved from apartment to apartment in our Sarlat house as renovations proceeded up to the summer of 2017. It took us five full years – five years of reading aloud before dinner – to reach Proust’s summit. It is true that, as we climbed higher, the thinner the air became, the more our view expanded to infinity. We became intoxicated by our perception of the height, paralyzed by vertigo at the sight of the bodies of other climbers lying prone on the slopes. We were enraptured by certain passages; we were often indignant by Marcel’s hypocrisy; we were amused by his malice. At dinner, the characters followed us in animated discussions as if they were neighbors.

Tea with Proust

Like Marcel, I too have always been under the spell of a name, capable as it is to capture the essence of a place. Geographic appellations work in two ways: either they crystalize their character for us, or we can form a complex impression of a place by assimilating its name alone. In other words, which comes first? Which one bestows to the other its magic?

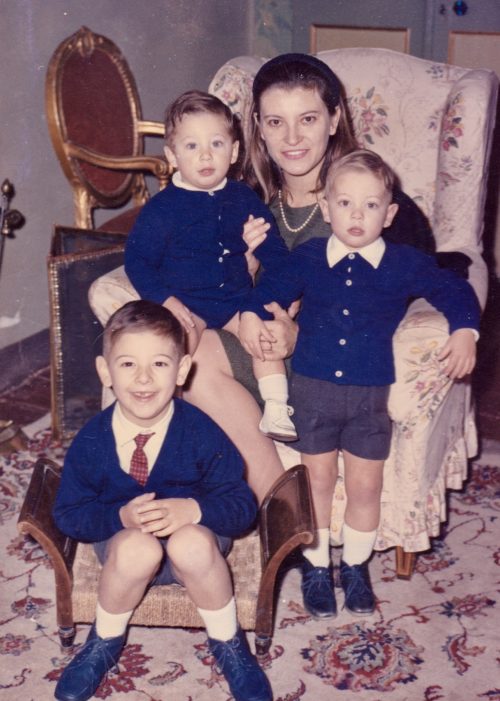

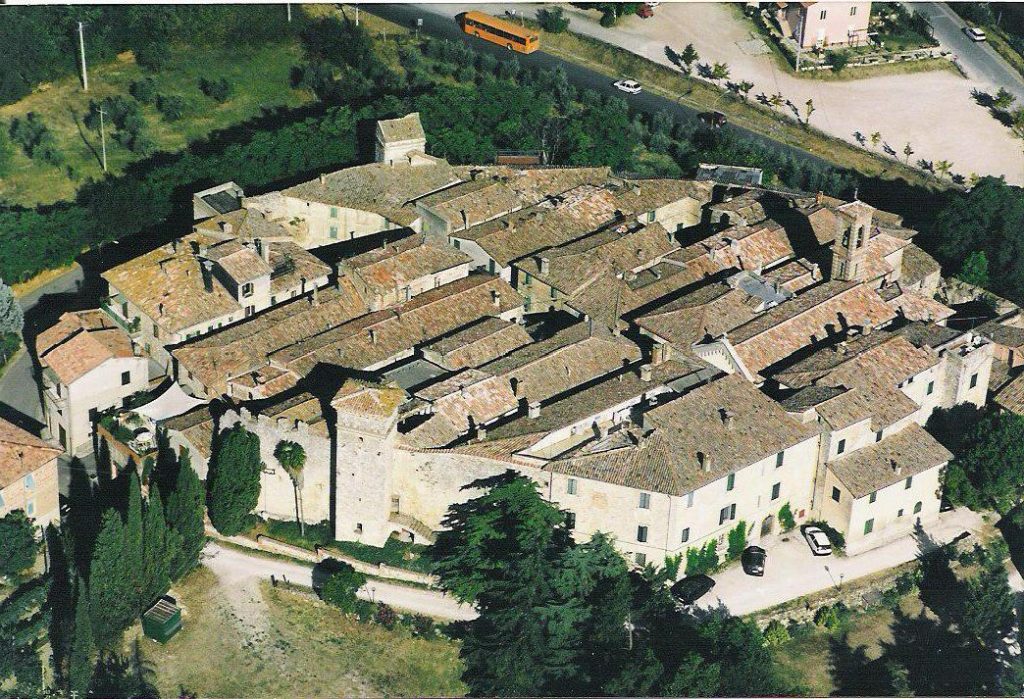

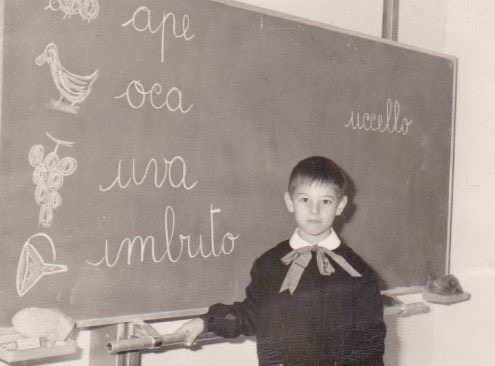

During my childhood, two places competed for my little world: the Umbrian village of Collevalenza – much of which was occupied by my family home – and Rome, where I was born, and where my family had its roots. In between the two, before the completion of the superhighway, a long and tortuous route twisted along river gorges and climbed countless hills, often making me sick. Returning to Collevalenza hinted at the aches and pains of the journey to reach that single hilltop, the colle, whereas reaching Rome – built on no less than seven, as I was always told – seemed relatively easy. My incredulity that such a short name as ‘Roma’ could contain such an immense city was great. At that early age, I loved my birthplace with unconditional love, and I thought I was the first to have discovered it; and that, when reading its name backward, it proclaims ‘Amor’.

My Combray – Collevalenza

My family moved from Collevalenza to a country estate called La Cervara. No other toponym has had so much evocative power for me, with its last broad vowels suggesting certain pastoral grandeur. The word cervo – deer – a noble animal that was never seen in the environs, added a touch of exquisite exoticism. It was like admiring a seventeenth-century Italian engraving, where the vista was gracefully framed by oak trees whose leaves were rendered by repetitive finger-like pencil strokes. La Cervara, our family home for almost twenty years was, however, rarely referred to as such: we didn’t go ‘home’ as much as come and go from La Cervara. That subtle difference made me indisputably sensitive to my fascination with onomastics.

Even before landing in Fossemagne, Dordogne, I was prepared for a bad surprise. The ‘big ditch’ that its late Latin root brings to mind, and the sense of stalemate that the series of consonants imply, materialized before our eyes on our first visit to the village – with its double row of houses clad in colorless resignation. To remedy that impression, we added the adjective ‘haute’ to the name of the property we had just purchased. Yet, even though it was on the heights of Fossemagne, at a fair distance from the village, La Placette Haute still possessed a diminutive ring to it, inexorably rhyming with words like midinette or salopette. During our stay, I must confess that this was a sore point for both of us. By virtue of the fact that part of our land fell under the jurisdiction of the neighboring hamlet of Ajat – a gem of a village gathered around its chateau – Dan adopted that as his address. As for me, what I would have given to make mine that of Auriac-du-Périgord, only fifteen minutes away, a name as delightfully sonorous as a cavity carved by prehistoric waters in sandstone.

Where the reading began: La Placette Haute

Later, as we were searching for a new property, we chewed on its name first. The manor house of Montchoisi was a tantalizing option for a while. Not only did it look like a decorous country home amidst mature trees, but the place name contained the idea of elevation and exclusivity, calling to mind scenes of rustic bacchanalia à la Watteau. Another property caught our attention in the haughty town of Hautefort, most regrettably sitting along the Allée de Bastard. The de Bastard family, that had ruled the village and its phenomenal castle for centuries must have made up for the unsavoriness of their name with the allure of landed prestige. But for us, it was an all too uncomfortable allusion to the Umbrian town of Bastardo that Dan and I dubbed ‘the town that dare not speak its name’. Of all the places where we ended up settling, Sarlat-la-Canéda has undoubtedly the most appetizing moniker. Whatever cooks in your mouth when you utter its name is redolent with traditional Périgourdin potatoes sautéed in duck fat.

Proust’s greatest gift to his readers – we know – is the key to lost time. His lost time is ours: Combray is our childhood; grandmother, aunt, mother and father, Gilberte, Albertine, the Verdurins, are there to remind us of our affections, our points of reference, our karmic knots. But I didn’t understand it right away. At the end of the reading, I rather thought that the characters would frequent the living room of my mind forever; that the breath of that unrepeatable era would continue to waft through my head.

Then came September 2019 and my friend Silvia Buitoni invited me to participate in her Internet group under the banner of the most Proustian of elements: the madeleine. I let myself get involved. But there again, it wasn’t immediately apparent to me that one madeleine would conjure another – a bit like what happened to Marcel himself – and that over the course of the year and a half that kept the whole world at home in lockdown, I would send Silvia as many as ninety ‘madeleines’. Several times – reasoning about the past in Aristotelian terms – I thought I’d run out of material. But memory, like creativity, does not follow a linear path, but unravels in cycles, or rather spirals. And on these spirals, like galaxies of time, memories shine indelibly.