But Who Was He, Really?

By Megan McKinney

Credit: Nancy Kriplen, The Eccentric Billionaire.

Credit: Nancy Kriplen, The Eccentric Billionaire.

Here is the richest man in Chicago’s history, back when he was young and handsome.

We have given the subject of this week’s feature a great deal of thought over a long period of time, not so much because the man was so rich—with today’s equivalent of as much as $125 billion. Our question was of a deeper nature, a genetic nature. How, we wanted to learn, could such a reportedly tightfisted curmudgeon be a brother of one the most loveable American men of the 20th century.

And there was something else. This man was responsible for making the innermost, personal dreams of more than 1,000 quietly creative people come true with a no-strings-attached gift of well over a half million dollars each. Furthermore, with the gift came the implication it was given because the individual was a “genius.” Now there’s altruism for you!

Chicago’s all-time richest man was John D. MacArthur. Here he is late in a life that ended in 1978 when he was 80.

Credit:Nancy Kriplen, The Eccentric Billionaire.

John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur, in whose names those “genius grants” are conferred.

Joining MacArthur in the adventure of becoming excessively superrich was the pretty teenager who was an employee in the insurance office of one of his brothers when John met her. They married—sort of—in 1937. But was it legal? No. Not till she sued him years later. By then, the smart little bauble who had helped pile up what was already a fortune knew everything. If there had been mail fraud or unreported income—we’re not saying there was, but if there had been—she would have known. She hired a team of sharp, well-paid lawyers and among her demands was half ownership of the company. It was about that time it dawned on old John D. that he had met an equal and, as The Eccentric Billionaire author Nancy Kriplen wrote about Catherine in her biography of MacArthur, “she had out-Johned John.” At this point, the relationship was redefined.

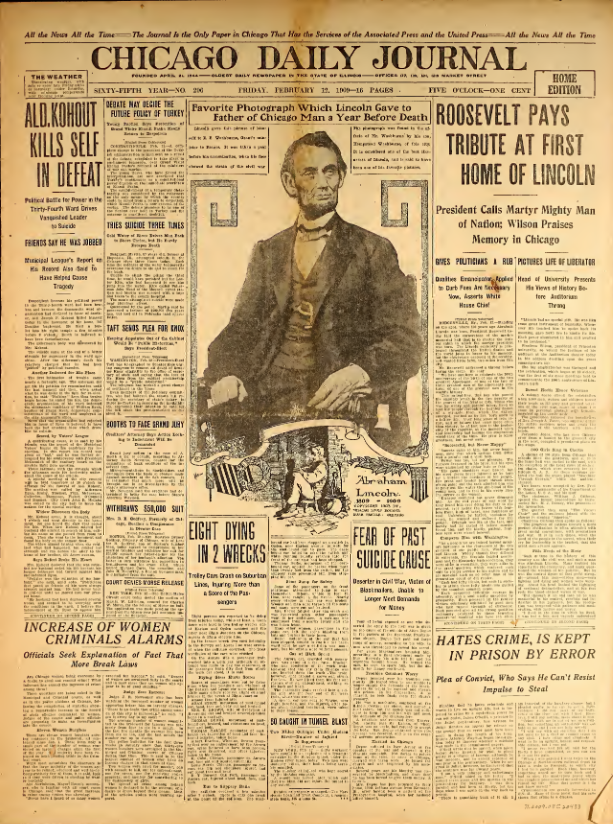

John’s brother, Charles MacArthur, was a Chicago newspaperman, a New York playwright and, with Ben Hecht, an Oscar-winning Hollywood screenwriter. Charlie was a favorite of The New Yorker magazine/ Algonquin Roundtable set, which included Robert Benchley—Charlie’s salad days roommate—and a one-time girlfriend, Dorothy Parker.

F. Scott Fitzgerald said of the loveable MacArthur brother, “Some men do not have to create something to prove they are artists. They have only to exist. Charlie is one of them.”

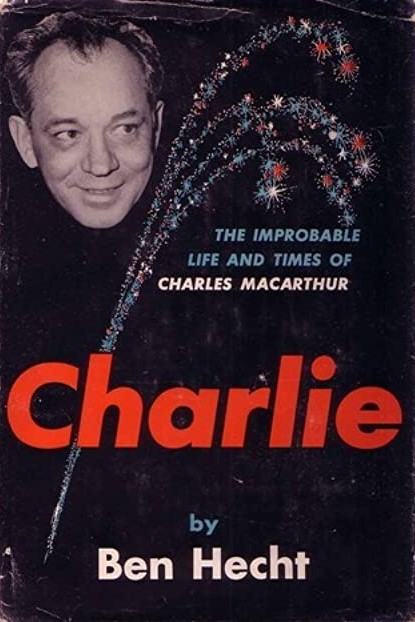

Ben Hecht, wrote, “The main thing about MacArthur was his attractiveness. He had a remarkable allure for every human who came across him…Men and women fell in love with him all over the place.” Hecht was one of these; he so greatly esteemed his friend and colleague, he wrote the 1957 posthumous book, Charlie, about him. In it the great screenwriter revealed that a staple suggestion during typical Hollywood story conferences was, “Let’s make the hero a MacArthur,” which meant, wrote Hecht, “Let’s have a graceful and unpredictable hero, full of offbeat rejoinders.” Among those who “played MacArthur” in this film or that one were Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, George Saunders and Robert Taylor.

“First Lady of American Theatre” Helen Hayes was so thoroughly captivated by Charlie MacArthur that she married him.

Their adopted son was James MacArthur, star of the long-running television series Hawaii Five-O.

Credit: Nancy Kriplen, The Eccentric Billionaire.

Credit: Nancy Kriplen, The Eccentric Billionaire.

The MacArthur family was captured in this image at the turn of the last century. The two youngest—dressed alike, as usual-—are in the front row; Charlie has his arm fondly around his little brother John. The bearded man in the center is the patriarch, William Telfer MacArthur. He was an evangelical preacher, who inspired even a “wavering” Billy Graham, but he also regularly beat his children and made almost no money. Did a childhood of physical abuse and dependency on the charity of congregation members inspire one child to become among the three richest Americans of his time and the other the most loveable? That we don’t know. But we did discover information about John D.’s astonishing “altruism.”

Credit: Nancy Kriplen, The Eccentric Billionaire.

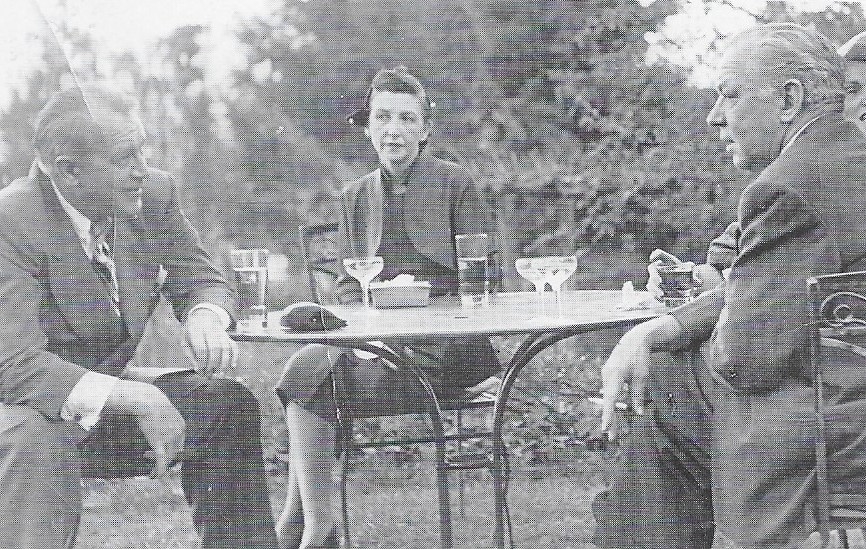

The MacArthurs: John D., Catherine T. and Charlie on the grounds of Charlie and Helen’s house, overlooking the Hudson River in Nyack, New York.

Credit:Nancy Kriplen, The Eccentric Billionaire.

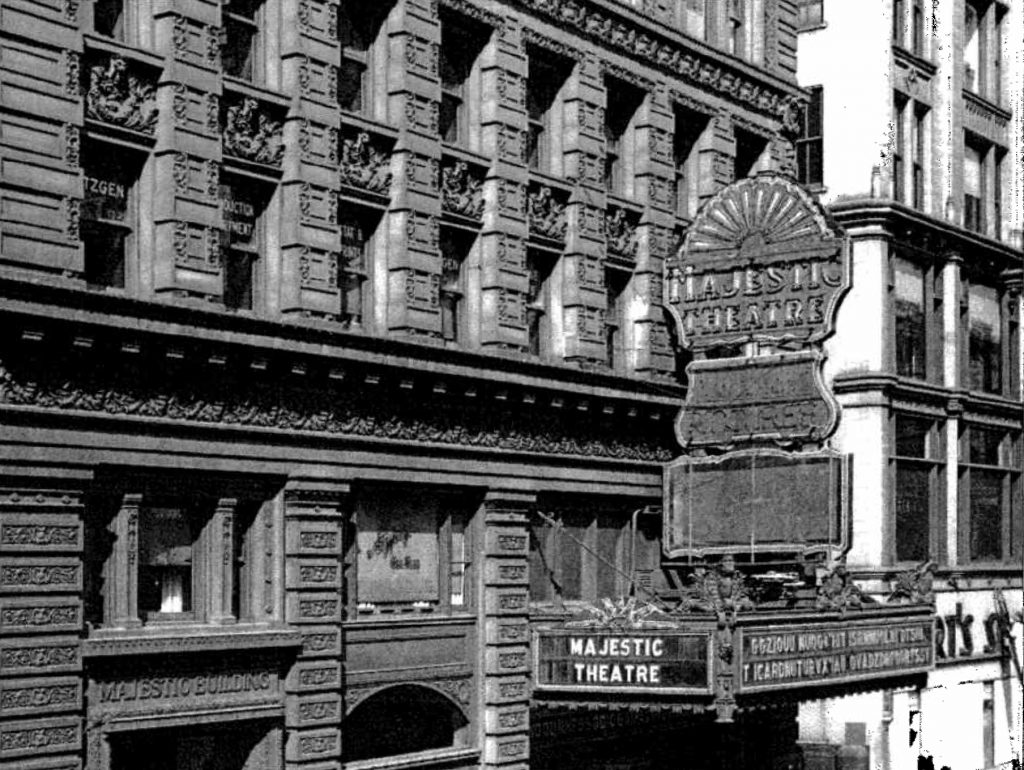

Bankers Life and Casualty Company, up on West Lawrence Avenue, and other insurance companies were the source of the MacArthur billions, plus some banks and a huge chunk of the state of Florida.

As possibly history’s most successful life insurance salesman, John D. cleverly never mentioned the unthinkable inevitability when discussing the need for his product.

John’s personal attorney, William T. Kirby, above, is the man the geniuses can thank for their collective millions. For years Kirby tried to talk with John about his own unthinkable inevitability. At the time, John’s estate plan left half the immense fortune to Catherine and the other half to the two children of his first marriage, Virginia and Rod.

In 1970, Kirby finally convinced MacArthur that the nearing inevitability would immediately produce two hated entities–government and taxes–which meant that almost everything he had built up “would have to be dismantled and disposed of at fire-sale prices to raise cash” to pay those taxes.

According to author Nancy Kriplen, Kirby’s pitch was, “This money is going to the public or for public good one way or another…So who do you want to make decisions about how it will be spent—’bureaucrats or people you trust?’”

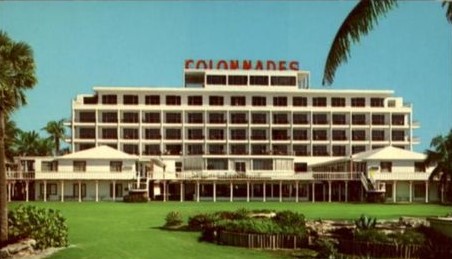

Therefore, one Sunday morning in October 1970, Kirby met with John and Catherine in their apartment in the MacArthur-owned Colonnades Beach Hotel on Singer Island in Palm Beach County.

Plans for the John D. and Catherine T. Foundation—which would keep the fortune intact—were wrapped up that day and not a word was said or written about genius grants, simply that the foundation would be operated for “charitable, religious, scientific, literary and educational purposes,” standard IRS language. John chimed in with a single sentence, “You guys will have to figure out after I am dead what to do with it.”

So much for personal altruism.

Edited by Amanda K. O’Brien

Author Photo: Robert F. Carl