By Cheryl Anderson

“May my legend gain ground, I wish it a long and happy life.”

—Chanel

“La Grande Mademoiselle”, is how the press referred to Coco Chanel. To this day, the title suits her. I say, with a fair amount of confidence, that the legend and allure of Mademoiselle Gabrielle Chanel will forever remain in the annals of fashion history as one of the world’s most influential couturiers. Chanel once said: “Fashion fades, only style remains.” She was the epitome of style, giving us lessons on how best to “pull it off” with confidence. She was a rebel, avant garde and a pioneer in fashion for decades. She left her indelible mark on everything she touched, (sometimes with scissors), and she approached business ventures with a ferocity, leaving a legacy of style we have loved to adopt.

Sketch of the eternal icons of Chanel. Karl Lagerfeld 2002

Another bit of her sage style advice was: “Before you leave the house look in the mirror and take one thing off.” Even when she wore a lot of jewelry at one time, it didn’t appear to be too much. I can only imagine what she took away to make the look positively perfect, but she always managed to make it thus.

There are myriad areas, or years of Chanel’s life, I did not write about. To name a few: her brief time in Hollywood, costume designs for the stage, her friendship with Misia, her devotion to Irebe, Reverdy, Cocteau, et d’autres amants, and her complicated life during and following WWII. She discovered talent and was patron to many—there is a lot to know about Coco Chanel. What I have shared with you on Classic Chicago, barely scratches the surface of what there is written about Gabrielle Chanel. If you take the time to search the internet, you can find short videos with the sound of Chanel being interviewed.

Chat with Chanel. Sketch by Karl Lagerfeld. How he imagined it could have been.

Coco Chanel worked until the very end. She ignored the Swinging Sixties, the obsession with youth, and stuck to an elegant modern style—trends are short-lived.

Paul Morand’s interviews with Chanel in 1946, while she was living in St. Moritz, gives the reader, in her own words, a deeper understanding of the legend. Morand’s manuscript, The Allure of Chanel, was discovered the year following Coco’s death—it had been put away in a drawer and forgotten.

In my articles, I always tried to get the facts right, piecing together what has been written, but in her own words: “My life didn’t please me, so I created my life.”—this sentiment has made it somewhat difficult to get the true and correct stories about her life even for all the authors I have referenced. One fact that eluded me, was exactly just how many Coromandel screens did she have, as they were among her most important possessions? The number varied from book to book to internet. In the interview with Morand, she told him that the number of Coromandel screens she owned was 21.

Chanel questions Lagerfeld. Sketch Karl Lagerfeld

What follows are direct Chanel quotes from Morand’s book. In the 1946 interviews with Morand, she was not sure where her creative life would take her or what the future held, but took the time with Morand to reflect:

“And many are the times that I shall continue to meet people who will talk to me about “Mlle C whom they know very well”, without realizing that it is her they are addressing.”

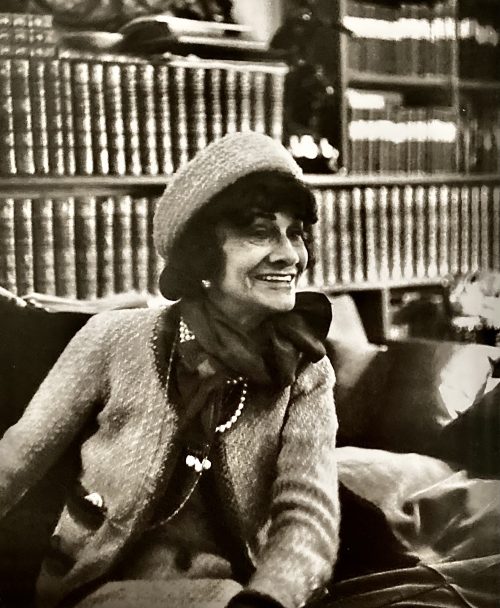

Chanel with her dear friend Claude Delay. 1970

“I have been a couturier, by chance. I have made perfume, by chance. I am going to take something else. What? I don’t know. Here again, chance will decide. But I am quite ready. I am not saying good bye for long. I am not thinking of anything, but when the moment comes, I feel I will pounce on something that will be within my reach. For quarter-of a century, I have created fashion. I will not begin again. It’s the age that is in chaos, not me.”

“ I have succeeded totally in everything I have undertaken.”

“If I think of aeroplanes, I would begin by making one that was too beautiful. You can always do away with it later. By starting out with what is beautiful, you can always revert to what is simple, practical and cheap; from a finely made dress, revert to ready-made, but the opposite is not true. That is why, when you go out into the streets, fashion dies its natural death.”

Sketch by Karl Lagerfeld as he imagined her.

“ ‘You’re never satisfied’, people say to me when they read those pre-war aspersions. I’m never satisfied with myself so why should I be with others? Besides, I like preaching.”

“I’ve never made a penny out of publicity. The couture business spent a fortune on maintaining publicity, which is more than nonsense, it’s an absurdity, since extravagance damages character.”

Models from the House of Chanel at the memorial service, L’Eglise de la Madeleine.

“I don’t understand how a woman can leave the house without fixing up a little bit—if only out of politeness. And then you never know, maybe that’s the day she has a date with destiny. And it’s best to be as pretty as possible for destiny.”

“I admire and love America. It’s where I made my fortune. I am French. I think I would be better understood there than anywhere else, because America does not work ‘for Americans’; that is to say, like our French couturiers do, with their gazes fixed on Life and Fortune [magazines].”

“There is luxury in America, but the spirit of luxury still resides in France.”

Chanel refused countless times to launch a fashion show in California, saying: “the outcome would be contrived and therefore a negative…Persia to the Pacific, they have tried to make wine, but they have never succeeded in creating the red wine of the Clo-de-Vougeot, or Vin d’Aÿ.”

“Wealth and technique are not everything. Greta Garbo, the greatest actress the screen has given us, was the worst dressed woman in the world.”

Lagerfeld’s sketch says it all.

“The legend has a harder life than the subject; reality is sad and the handsome parasite that is the imagination will always be preferred to it. May my legend gain ground, I wish it a long and happy life.”

“My life has been merely a prolonged childhood. That is how one recognizes the destinies in which poetry plays its part.”

“But for me, in the Switzerland of today just as in the Auvergne of yesteryear, I have only found loneliness.”

It’s sad to know how alone she was at the end of her life, alone in her rooms at the Hôtel Ritz. So many of her friends and lovers were gone, leaving her in isolation and loneliness. She was looked after by her retinue of staff, a butler, a maid, Céline, and her secretary, Lilou Grumbach. Her butler, François Mironnet would sometimes take off his white gloves, sit down and eat with her. Lilou ofttimes played cards with her.

Graveside Lausanne, Switzerland. 1971. Yves Saint Laurent leaving the memorial service.

Her rooms at the Ritz were modest, the bedroom overlooking the gardens and the rooftops of rue Cambon. They were the same rooms she occupied after the invasion of Paris—she kept them after the war and during peacetime. The walls were white as were her sheets, “everything simple and austere as a nun’s cell.”, says Picardie.

Claude Delay remembers: “I often found her alone here, sitting at the dressing table, gazing down into the garden, looking at the Chestnut trees. She was still so slender, thin as a girl in her white pajamas, her eye brows washed clean of their black makeup, her jewels put away beneath a chamois cloth, a silk scarf tied around her hair. “One shouldn’t live alone”, she said. “It’s a mistake. I used to think I had to make my life on my own, but I was wrong.’’

Madame Gabrielle Palasse-Labrunie’s picture as a young girl was on the mirror of Chanel’s dressing table at the Ritz—Chanel was Labrunie’s great aunt. She and Claude Delay were the closest to Chanel late in her life.

Labrunie said of Chanel: “Nobody can possess her spirit—she was the embodiment of independence and freedom. Nobody could buy her and she is not for sale.”

Her chauffeur sometimes drove her to Cimetière du Père- Lachaise. Chanel enjoyed walking among the graves. Not because there were people buried there that she knew or loved, but as a child, she had walked amongst the graves in another place.

Mademoiselle was working on her collection the day before she died, a Saturday—even she could not force her employees to work on Sunday. So, Claude Delay came to visit her at the Ritz on that Sunday, January 10, 1971, at one o’clock. She found her at her dressing table at the Ritz applying make-up, dark eyebrows, and red lipstick, closely examining herself in the mirror. They had lunch downstairs at Chanel’s regular table—a table tucked away where she could see the other people, but she herself could not be seen.

Chanel working. Photo Henri Cartier-Bresson 1964 She was still working the day before she passed away on January 10, 1971.

Following lunch, and well after all the others had left, her chauffeur drove them for an afternoon drive. Delay remembers the Champs-Elysée was, “crammed with a gloomy crowd.”

Picardie writes: [they drove] “through the streets of Paris, while a wintry sunshine finally emerged through the mist. Chanel told Delay that she hated the setting sun, that she should have worn her dark glasses. By the time the car had brought them back to the Ritz, the sun had disappeared, and a full moon was rising. Delay said goodbye, and as Chanel disappeared through the door of the Ritz, she called out that she would be working again at Rue Cambon, as usual, the next day.”

Memorial in Parc du Cap Martin. Photo Cheryl Anderson

Once upstairs, she told her maid, Céline, she was very tired and lay down on her bed fully dressed—she did not want to be undressed. During the night she called out to Céline that she couldn’t breathe. “You see”, she said to Céline, “this is how one dies.” She would pass away during the night, January 10, 1971. She was 88 years old.

The last evening dressed she designed for herself in 1970. Worn on several occasions before her passing. Simplicity at its best. Topfoto

The next day, Delay remembers seeing Chanel in her bed dressed in a white suit and blouse, hands were tucked beneath the linen sheets. “She looked so small,” says Delay, “almost like a little girl.” Her maid had lovingly dressed her.

“No one is young after 40, but one can be irresistible at any age.” Chanel

Thirty years later, as he was nearing the end of his life, Paul Morand remembers the last words Chanel said to him in Switzerland, the winter of 1946: “I would make a very bad dead person because once I was put under, I would grow restless and would think only of returning to earth and starting all over again.”

Gabrielle Labrunie: “She did not want to be buried beneath a stone monument. She’d said to me, ‘I want to be able to move, not be under a stone.’ ”

Chanel with Cocteau and Miss Weiseveiller in Rome.

Illustration by Jean Cocteau of Chanel. 1937

The funeral was at L’Eglise de la Madeleine, located close to rue Cambon, and noted for its portico of stone colonnades. Picardie’s description: “Her coffin was set beneath the statue of Mary Magdalene, and covered with white flowers—camellias, gardenias, orchids, azaleas; some formed into a cross, others in the shape of scissors—except for a single wreath of red roses.”

Chanel gazing up at her chandelierin her apartment at 31 rue Cambon. Condé Nast Archives

In attendance were couturiers, Yves Saint-Laurent, Balmain, Balenciaga, and Courrèges. Indeed, so many of her friends and lovers were no longer living, but Serge Lifar, Jeanne Moreau, Salvador Dali, and all of her models were there, wearing couture.

She is buried in Lausanne, Switzerland. The headstone has five lions carved across the top, her name above the dates of her birth and death, and a simple cross. The grave is covered in white flowers, and per her wishes, not under a stone.

Chanel touching up one of her 21 Coromandal screens.

Mademoiselle’s last couture show was two weeks later and those same models present at the funeral paraded by in ivory tweed suits and white evening dresses. It’s been noted that some in the audience could be seen glancing at the top of the mirrored staircase where Coco Chanel would sit. One can only imagine the atmosphere in the room—somber, I would imagine. Gone forever from her friends and the world was the only fashion designer to be listed on Time magazine’s 100 most influential people of the 20th century.

Chanel in a straw cloche hat wearing a jacquard suit.

My interest in writing a series about Coco Chanel all started because I was aware that her villa, La Pausa, was up the hill from my favorite places in France, Menton, and Cap Martin. She traveled the same roads and strolled along the same beaches on the coast that I have. My hope is that someday the villa will be open to the public. I will walk along the paths in the gardens and marvel at the interior of the villa where sits her past in the architecture and the atmosphere she alone could have created.

I’m ending the series with pictures and Lagerfeld sketches, heretofore I have not posted, or maybe a few repeats—and, one last one of me in the suit I wore to get married at the Fürth, Germany city hall. A black Breton-style hat completed the look. I have always loved the Chanel style and will forever go forward. One can never go wrong. As Lagerfeld put it: Coco Forever.

Chanel Sketch by Karl Lagerfeld. He caught her in a work position pointing her finger–perhaps checking a hem.

A sultry Gabrielle Chanel. 1920

Cecil Beaton photo 1965

Chanel Sketch by Cecil Beaton 1969 |

Cecil Beaton’s portrait of Chanel at work. 1960 |

Chanel in 1964. Photo Henri Cartier-Bresson. Her engaging smile–one of my favorites.

Me in an off-white bouclé suit trimmed in burgundy on the day I was married at the Fürth, Germany town hall. Loved the Chanel “look”.

The name on the upstairs studio remains as before—Mademoiselle – Privé

À bientôt

Quotes and pictures:

Coco Chanel: The Legend and The Life, by Justine Picardie, published by it books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

Chanel and Her World: Friends, Fashion and Fame, by Edmonde Charles-Roux, published by The Vendome Press

Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, by Janet Wallach, published by Doubleday

The Little Book of Chanel, by Emma Baxter-Wright, published by Carlton Books

Chanel’s Riviera, by Anne de Courcy, published by St. Marten’s Press

Chanel: Collections and Creations, by Danièle Bott, published by Thames & Hudson

The Allure of Chanel, by Paul Morand, published by Pushkin Press 2017 Translated from the French by Euan Cameron

The Golden Riviera, by Roderick Cameron, published by Editions Limited

Diana Vreeland -The Eye Has To Travel, by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, published by Abrams, New York

French Riviera – Living Well Was the Best Revenge, by Xavier Girard, published by Assouline.

Marietta Peabody FitzGerald Tree

Marietta Peabody FitzGerald Tree

A portion of the Tree house on Manhattan’s Upper East Side

A portion of the Tree house on Manhattan’s Upper East Side