A Northwestern Professor and Kellogg Students Are Poised to Opine Whether Pricey Super Bowl Ads Score

The phenomenon will occur during Super Bowl LV on CBS. There is no bigger advertising platform in the United States than the annual NFL title game. Of the top 10 highest-rated TV broadcasts in the country, nine have been Super Bowls (the last episode of M*A*S*H in 1983 is the outlier). And the ads during the game — at the price of about $5.5 million per 30-second slot, the biggest price for commercials every year — have become a huge national story themselves, as wags debate who won the public’s heart and who dropped millions of dollars in a lost cause.

One of the most popular assessments of these pricey plugs derives from the insights of more than 50 MBA candidates at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. Known this year as The Kellogg Bowl: 2021 Super Bowl Ad Review, students — who will gather on campus wearing masks and via Zoom — will appraise about scores of commercials for their effectiveness in building a brand.

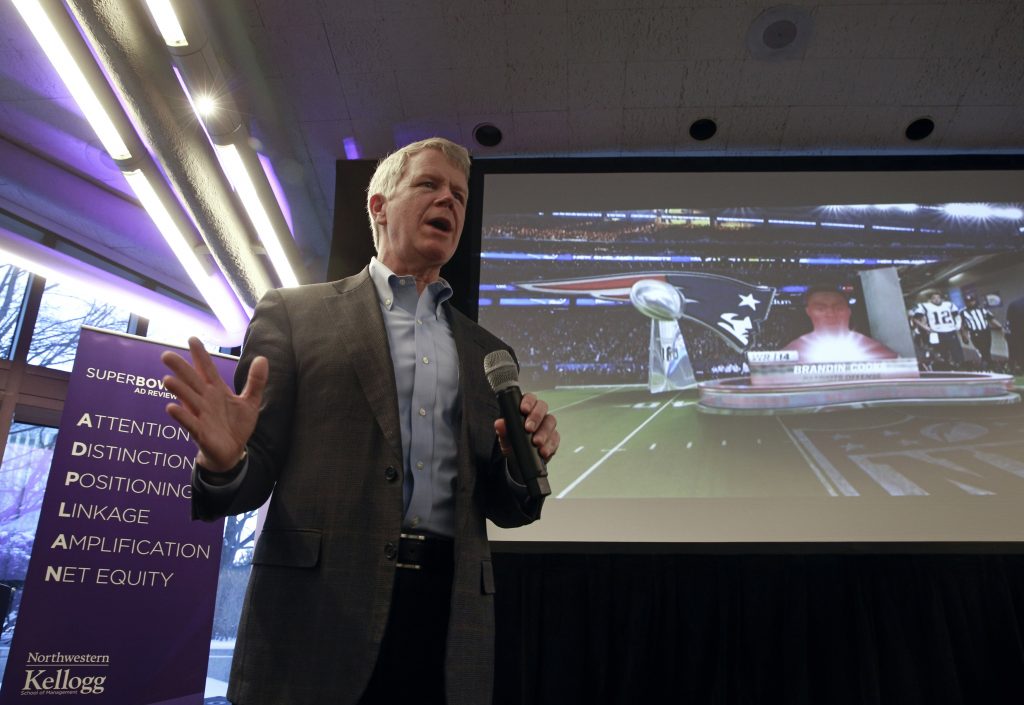

The Kellogg Bowl: 2021 Super Bowl Ad Review will be led by professor Tim Calkins (right) with assistance from professor Derek Rucker.

The ad review is the brainchild of Tim Calkins, clinical professor of marketing at the renowned grad school. Launched in 2005, Calkins based the idea around a discussion he initiated in the marketing department at Kraft every year the day after the Super Bowl.

“Our Kellogg event is unique because we focus on efficacy,” said Calkins, who holds a bachelor’s degree from Yale University and an MBA from Harvard University. “Which spots are likely to work and build the brand? We often hear from advertisers before and after the game; people really follow our rankings.”

Calkins said students gain valuable experience ranking advertising and thinking strategically about marketing initiatives.

“Evaluating upwards of 70 spots in a row is a memorable experience and develops analytical skills,” said Calkins, who will discuss this year’s findings at a Harvard Business School of Chicago event on Feb. 9. “We use a framework to evaluate the ads in a rigorous and disciplined way. Instead of asking, ‘Do I like this ad?’ students analyze it and ask, ‘How will it impact the brand?’”

“We often hear from advertisers before and after the game,” Northwestern professor Tim Calkins said of the school’s Super Bowl Ad Review.

Poised for the 17th iteration when the game is played on Feb. 7 in Tampa, Calkins has witnessed a handful of changes, such as advertisers who now create integrated campaigns with press releases and teaser spots and even reveal the actual ad well before the game starts. And compared to 2005, when neither Twitter nor Instagram existed, “social media has become a huge part of the mix.” Calkins said. “It heightens the impact for advertisers that do well and advertisers that miss the mark.”

The revenue these ads command is astronomical. During last year’s battle, Fox raked in about $600 million during the contest and from the pre-game and post-game shows (of course, the network also pays the NFL a massive amount of money for the right to air games). It’s unclear whether CBS will enjoy a similar windfall in February, especially since brands may be unsure of the most appropriate tone to strike amid a pandemic.

“This year is a huge challenge for marketers,” Calkins said. “Some advertisers will use humor, but they risk seeming inappropriately light-hearted. Other advertisers will run more serious messages, but these may all blend together and seem out of place for a fun sporting event.”

Tim is an author of a number of books related to marketing, including How to Wash a Chicken: Mastering the Business Presentation.

What makes a great Super Bowl ad? Calkins is clear on what’s needed. “If a spot is going to work, it has to attract attention and break through the clutter,” he said. “It also needs to communicate a benefit, a reason for people to buy the product. The branding has to be clear, and the ad has to reinforce existing brand equity. To do all that in 30 or 60 seconds is not easy.”

Calkins said he has seen many wonderful Super Bowl ads, but his personal favorite is Google’s 2010 spot. Called “Parisian Love,” it told a story through a series of Google searches. In terms of flops, he cited a 2011 spot by HomeAway that featured a baby being thrown against a wall (the company was forced to apologize). But he saved his biggest flop for a 2015 commercial by insurance giant Nationwide, which featured a child who had passed away.

“The goal was to encourage people to prevent accidents, but viewers were offended at the dark message that seemed out of place during the Super Bowl,” he said. “The marketer behind the spot left the company not long after. A Super Bowl miss can end a career.”

The Sporting Life columnist David A. F. Sweet can be followed on Twitter @davidafsweet. E-mail him at dafsweet@aol.com.