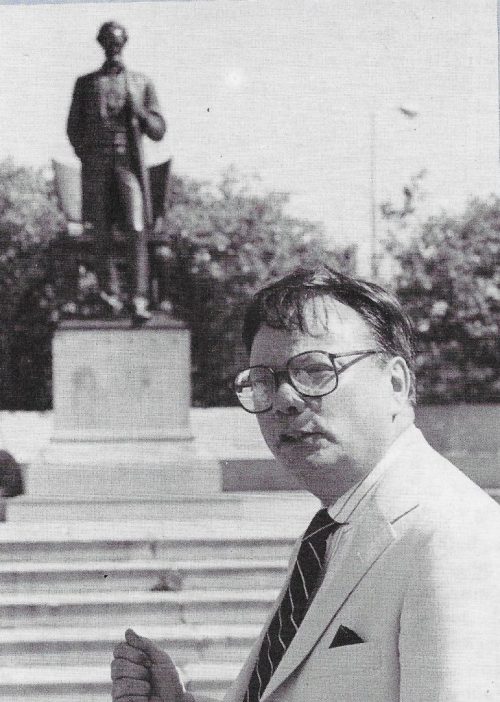

By David Garrard Lowe

When I am in Chicago and have the good fortune to be in residence at the Athletic Club on North Dearborn, I often walk to the end of the street and into Lincoln Park. There I pause, as though at the entrance to a holy shrine. I see him in the distance, the gaunt figure created by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, looking down, contemplating the world and time and mankind.

I continue through the garden laid out before him, a garden that exemplifies how he has rarely been understood. The garden was conceived as an informal, prairie-inspired tribute in deference to Lincoln’s Illinois heritage. What a misconception! People frequently underestimate Abraham Lincoln, viewing him as the prairie dweller, the woodcutter, the modestly attired small-town lawyer. That’s what they envisioned in New York when, in 1860, he was invited to come east to give a speech in Cooper Union’s hallowed Great Hall. Most expected to see a country bumpkin and be amused by his quaint speech and his rural appearance and manner. But the Lincoln that appeared that night to a jam-packed hall was certainly no bumpkin, neither in mind nor manner. The eloquent words flowed as they might have from an Old Testament prophet or a Shakespearean king:

“Let us have faith that right makes might; and in that faith let us to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

Alas, the gross misconception about Lincoln continues in this garden. But as I approach the tall bronze figure, with its delicate hands and smart tailcoat, prairie fantasies dissolve. I like to sit there, near him, and imagine that he is looking down upon me, articulating those memorable phrases, the greatest of any American President.

“With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

Only a genius of the language would think to use ‘bind’ when speaking of the horrors of our most bloody war. Sitting there, I feel his presence, because Chicago is his holy city. Here, he was the lawyer of the Illinois Central Railroad, once so emblematic of the windy City. He seems to speak, for the likeness that Saint-Gaudens so subtly created portrays him in the act of delivering an oration. I can almost hear him ask,

“Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better or equal hope in the world?”

Looking to my left I spot the rear façade of the Chicago Historical Society, now the Chicago History Museum. There, like the contents of a pharaoh’s tomb are his precious relics, among them the small bed upon which he was laid after being carried from Ford’s Theater and in which he died in the early morning of April 15, 1865. “Now he belongs to the ages,” observed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. I like to sit quietly and look at him. On one particular occasion, a voice intrudes on my musings: “Who is that?” The person speaking has brutally broken into my reverie. I hesitate to answer, “Abraham Lincoln;” it is like being in a venerable church, gazing at the crucifix with a voice breaking in “Who is that?” One can’t say, in all seriousness, “Christ.” I feel that it is just as inappropriate to say, “That’s Abraham Lincoln. “But after repeated requests, I softly answer, “It’s Mr. Lincoln.” And I hear them say among themselves, “Who?” and I answer no more.

In a very real sense, so much began and ended for Lincoln in Chicago: the young attorney’s success representing the Illinois Central; the Wigwam on the lakefront, where, at the 1860 Convention, the freshman politician was nominated as the candidate of the new Republican Party; Saint James Episcopal Church, now Cathedral, where the new President worshipped for the last time before embarking on the long rail journey to Washington. And then that heartbreaking day, May 1, 1865, when his body was returned to the City on the Lake in one of Chicago’s great inventions, a Pullman car. The city was eerily quiet. The catafalque was accompanied by 100 women in white dresses. And the streets were strewn with straw to muffle the sound of the hearses’ wheels. Like a majestic galleon, the hearse moved through the streets to the Cook County Court House. There, the coffin was opened, revealing his spectral white face, still noble, for, as they used to say, he had good bones. The crowds filed in reverent silence past his bier.

Heard on that solemn day was a new song by the noted American composer George F. Root:

Farewell Father, Friend and guardian,

Thou has joined the martyrs’ band;

But thy glorious work remaineth,

Our redeemed, beloved land.

Later, he would be carried to his final rest in Springfield. But still he lingers in Chicago, in the park named for him; in the museum with his precious artifacts; and in this spot where stands this heroic image of our 16th President, this man from Illinois, with his elegant presence and, more importantly, his elegant mind.

David Garrard Lowe

January 2020

Photo Credit: Laszlo Kondor, AVENUE M magazine