BY JUDY CARMACK BROSS

Just in time for a Valentine’s dinner date, here’s a little food for thought from Rebecca Spang and Richard Shepro, two pundits proudly presenting February 13th at the Alliance Francaise of Chicago.

Aimee Laberge, the Alliance’s Director of Programs, told us more: “If, like me, you are very curious about who said one has to have red wine with steak or when restaurants were invented, this is the Alliance Française program for you. Why? Because we get two experts on these subjects to enlighten us in no holds barred conversation—and, of course, after the talk, you get to test your own skills at wine pairing with Chablis and Morgon plus rillettes de canard et fromage à pâte molle!”

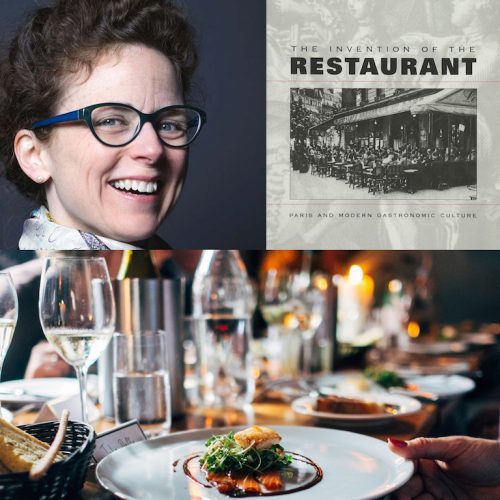

Indiana University history professor and author of The Invention of the Restaurant, Rebecca Spang brings us back to eighteenth-century Paris where the institution of the restaurant was beginning to shift from a purveyor of health food to a symbol of aristocratic opulence. With the subsequent reinvention of our modern culture of food and fine dining, the social life of the entire world was forever changed.

Attorney and scholar of law, economics and food history Richard Shepro will reveal the true history of the four essential methods of pairing he discovered in research he published for the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery. He brings us on a tour of French regional cuisine to find out why a dish is “married” to a particular wine—and why those not respecting the rules might be regarded as unrefined or ignorant. You will be surprised to find out that most of these “marriages” are not so old, and even “red meat with red wine”—erroneously understood today as the most immutable of wine pairing rules—has an elusive, recent origin.

After speaking with Spang and Shepro, we can’t wait to hear the dialogue and debunking. Although they haven’t met, Spang says they have plenty in common: “We are Twitter friends and Harvard graduates, both interested in the history of food. I am proud that Indiana University’s Lily Library houses Rick’s grandfather’s books on clocks.”

It was actually while at Harvard that Spang focused on the history of food. “Today, undergraduate and graduate degrees are available in food studies at many universities, and Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library at Harvard houses Julia Child’s and other rare cookbooks,” she shares. “However, when I told my advisor as an undergraduate that I was interested in studying the history of food and everyday life, he drew himself up and said, ‘Miss Spang, you can’t study home economics at Harvard.’ ”

Spang ignored those early rebuffs and the Harvard University Press would go on to publish the Invention of the Restaurant, which won the Press’s top prize.

“When someone asks when the first restaurant appeared, I can easily say March 1767 when Au Restaurateur opened in central Paris,” she says. “A far cry from the everything-you-can-eat-buffet, it was begun for people who described themselves as too weak to eat a big meal at home. They just wanted a little something—think small plate today. A couple of types of bouillon, usually beef and chicken, were on a printed menu, which guests sipped with perhaps a glass of wine which was labeled as ‘pure and unadulterated,’ meaning that the color of the red wasn’t made artificially darker or the white thinned.”

Spang reveals that rice pudding was added a little later, also thought to be suitable food for the clientele. The street where the restaurant, she says, which sat twelve to fifteen people at tables of two to four in two connected rooms, was destroyed when Paris was re-configured.

For any occasion, Spang looks for restaurants that have their own ambiance and atmosphere: “So many public establishments are so aggressively branded and pushy and resemble Las Vegas. I like a more subtle place. I think anyone over 35 would agree: no loud music. It is definitely true that many restaurants intentionally create bad acoustics so that guests can’t hear one another and tables will turn over faster.”

The Shepros have been Symposiasts at the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery since 2012. He has given five lectures there and published four scholarly papers including: The Degrees of Freshness: Contemporary Market for Hyperfesh Seafood; The Rhetoric of Salmon: The War of Words, Images, and Metaphors in the Battle for Wild-Caught vs. Farmed Salmon; and True Bread, Pizza Napoletana and Wedding Cakes: The Changing Ways Legal Power Has Shaped Bakers’ Lives.

With just days before Valentine’s Day, we got right to the heart of things with Shepro:

What would be a perfect food and wine for that sweetheart of a day?

Wine and food are all about memory. For the first Valentine’s Day, my wife, Lindsay Roberts, and I celebrated, I made Chateaubriand and served it with Château Giscours, a red Bordeaux from Margaux, so we both have a soft spot for that pairing. Of course had we blundered and served that beef dish with a white Sancerre, we might not be looking to repeat the experience.

What are myths you debunk and how did they get started?

I should start by saying that the categories I describe in my 2017 Oxford paper are my own creations, based on my historical research and 40 years of talking with sommeliers and chefs and observing people. Those categories form the basis for the book version of the paper that I’ve been working on since I gave my lecture.

One myth is that there is a best French wine for every French dish, and that these pairing rules are centuries old. But another is that there really are no rules and you should just drink what you like.

Wine and food can support each other, creating a synergy where the sum is so much greater than the parts, or they an clash badly. I have had a visceral reaction to people serving me white wine with rare beef, which has happened three times in my life.

I relate in the paper the story of the supposedly lighthearted electronic wine-pairing game at the Cité du Vin Museum in Bordeaux. They say it’s lighthearted, but if you pick something that is clearly a blunder, you will be chastised. Just as there are differences in dress between France and the US that people care about, there are differences in wine behavior. You won’t see French people drinking red wine as an aperitif at a party!

Everyone loves tips. What would you share about pairings?

One thing is to learn from a good sommelier and talk with that person. A really good sommelier knows the wines in his or her cellar like they know their friends and understand the changes in these friends as they age, so they know the right wine at the right time. The more you discuss the wines and your own likes and dislikes with the sommelier the better they can advise you.

In the US the sommeliers at Le Bernardin in New York are the most like the sommeliers I like in France. The wine crew in Chicago at Band of Bohemia is superb: although the restaurant is known for the beers made on the premises, they have a wine list made up of wines that really match their food, and every one is available by the glass.

What do you find most special about French food?

French food was the first I encountered that was a real art form—not in the sense of being exotic or elaborate but a cuisine where people used all their faculties—and took as seriously as they took art or music. I remember when I was a graduate student at the London School of Economics dining on a trip to Paris in a small, not especially celebrated, left-bank restaurant, Clos des Bernardins, and seeing how serious and dedicated the director of the dining room was. He was an all-seeing perfectionist but not a showman. It was a revelation.

I only discovered last year that the great chef Joël Robuchon had been chef de partie there as a young man. I love how great even modest restaurants in France can be—so many are so knowledgeable and have such high standards.

Do you have a favorite French dish? If so, what wine would you pair with it?

Favorites are difficult. I sometimes think I have a favorite opera when I am immersed in it, but that is just for that evening. If squab is on a menu, I almost always order it. I had a very simple and magnificent squab course recently at Blackbird prepared by its chef Ryan Pfeiffer. I had it with one of the great Burgundies: a Richebourg.

Often I think of blanquette de veau as my favorite dish—and there is a controversy over whether it should be paired with a white or a red. A good idea is Santenay, one of the southernmost plots in Burgundy and one of the few spots in Burgundy that makes both white and red wine.

Wishing that I could take all our readers into your kitchen, tell us about its definite functionality and charm.

Through frequent travel to France for both work and pleasure, I’ve seen many sides of France and gotten to know many chefs well. We have had a long association with the celebrated chefs Michel Guérard and Joël Robuchon, who influenced the design of our kitchen at our Lakeview home.

Although we worked on the kitchen with Chicago architects Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge, the feature story Food and Wine magazine did on our kitchen focused on the advice, design, and inspiration we had from Robuchon and Guérard and their colleagues—how it was both high tech, with many specialized modern tools, and low tech, with mortars and pestles, a wood-burning oven, and a fireplace we can cook in.

Tell us about your involvement with the Alliance Française.

The Alliance Française, like Lyric Opera of Chicago and a few others where I serve on the board, is really dear to my heart. The people there and many of my fellow board members share my love of French culture and work very hard to help others share what we love. Aimée Laberge, who is also a novelist, plans wonderful programs and pours her heart into it.

Why not pour yourself into “Talk and Taste! The Invention of French Restaurants and Wine Pairing” next week—and pour yourself a glass!

For more information on programming at the Alliance Francaise Chicago, visit af-chicago.org.