By Francesco Bianchini

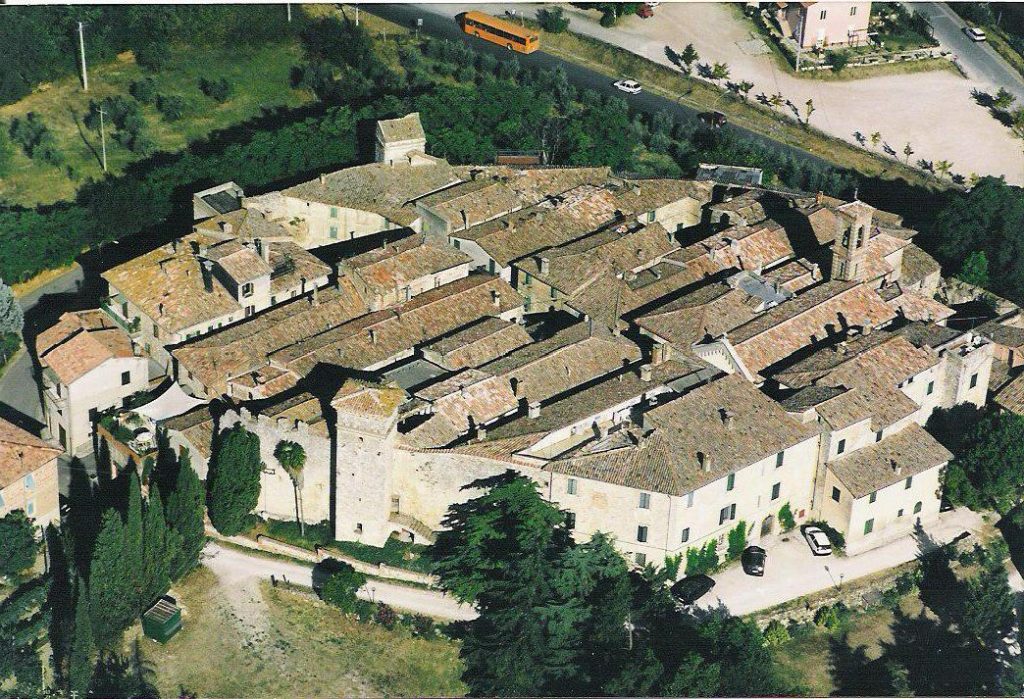

Collevalenza, with my childhood home stretching across the entire bottom of the picture

In my childhood home, a lot of space was devoted to storing food. Milk, cheese, sausage, eggs, vegetables, oil, and wine came from our farm below the house. From the scullery, there were a series of rooms, each with a specific function, and each distinguished by its smell: nauseating to me, pecorino, caciotta, and ricotta cheese, lying on long wooden boards; the acrid and sweetish aroma of must and wine; the appetizing perfume of salami, sausage, capocollo and hams that hung in festoons from the beams. There were also cupboards of preserves, pickles, and jams, and little rooms with ancient terracotta oil vats.

Nothing was kept under lock and key, a Garden of Eden where temptations were part of the divine plan. I never had a sweet tooth, unlike my brother Fabrizio who perfected the art of emptying a box of chocolates by making an invisible incision in the cellophane. It is certain that my mother, who kept boxes of sweets stacked in her linen closet, was stunned when she opened them. A burglary worthy of Arsène Lupin, the fictional gentleman thief of our favorite TV series.

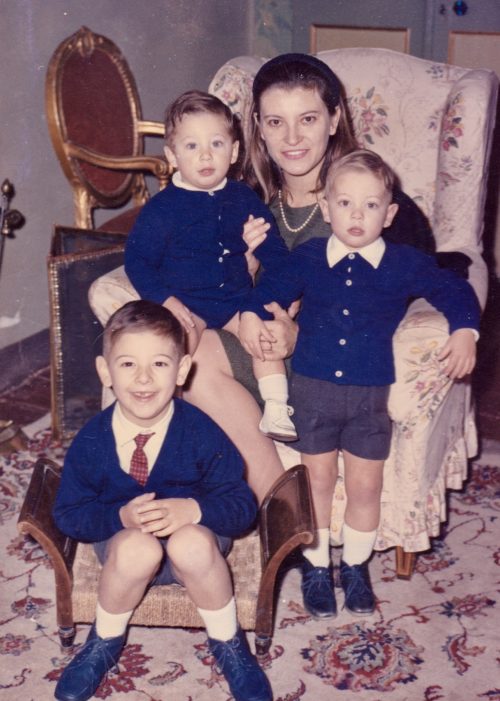

Sausage stealer, front left, chocolate candy thief on Mama’s lap, and my angelic brother Filippo

On some Fridays, a day of abstinence from meat, even worse during Lent – the sacred Ramadan of Catholics – I was taken by an afternoon languor for a dry sausage. I didn’t need a snake to be tempted by those coiled garlands that I sometimes merely visited to inhale the smell. Not enough to maintain my righteous intentions! With a knife, I cut the connecting thread and detached a sausage from the twisted gut that held the chain together. The good ventilation of the charcuterie room ensured perfect drying. The skin came off effortlessly and floated in the air, leaving the pinkish-brown sausage naked and ready to be bitten. At times, what with the risk of being caught, I didn’t even have time to peel it.

They’ll never miss one…

In the absence of guests, breakfast in our house was a hurried affair. By the time we arrived at the kitchen table, Augusta had already boiled the fresh milk that arrived early each morning from the farm, ferried in the aluminum containers that are seen nowadays in flea markets, and Rodolfo had set the marble table with mismatched cups, bread, butter, and jam. If we were daydreaming or had come down late, the Ovaltine would have congealed on the surface of the scalded milk. We called that “veil” in disgust and fished it out with a fork, or demanded that Rodolfo start all over again.

During school terms, my mother invented health protocols: a spoonful of cod liver oil, for example, administered before breakfast was met with a multitude of antics on our part to make the process as exasperating as possible. Our elementary school was only a few hundred yards from home, which we reached by passing the bar and grocery store where my classmates stocked up for recess. But I was never given money, moreover, my mother had an intense aversion to snacking. When the school bell rang at ten thirty, there would be a great deal of unwrapping and sandwiches would appear, overflowing with mortadella, finocchiona, prosciutto, or a warm schiacciata – a typical Tuscan bread, baked in an oven with olive oil and salt, onion and rosemary, or tomato. I would find myself looking into a corner with my mouth watering, except for the times when Rodolfo – predisposed to indulgence and happy to subvert the educational rigors of my parents – would sneak something into my school satchel.

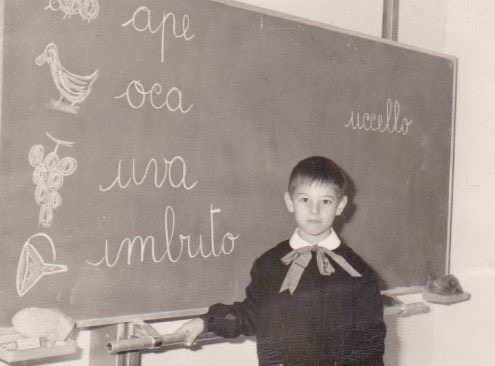

The poor starving boy in his 1st-grade uniform

We write about the food of the heart and soul, about memories and people, but rarely about the place where food is prepared. I’m not referring to the precious gastronomic boudoirs of our times – immaculate, super-technological, fancy, or retro – but to the workshops of old, the purely utilitarian rooms where guests didn’t stick their noses, and which exert a poignant fascination on me. Eons passed and the equipment evolved, but without the pressing need to get rid of the old. The stufa economica, relegated to a corner, continued to provide warmth especially in times of energy-saving. Cooking had moved on from gas stoves – whose cast-iron burners, operated by large bakelite knobs, hissed when lit – to slimmer and safer models, perhaps with a ventilated oven. The refrigerator had also been modernized; next to the travertine or white ceramic sink a dishwasher had found its place, and on a shelf or sideboard the microwave made a discreet appearance. Fashions followed one another, but due to providential indifference or lack of means, the old terracotta floor, sometimes chipped and sagging; the early twentieth-century cement tiles or the 1920s terrazzo had been preserved and polished with devotion. The kitchen was also the point where everything in the house bounced, settled, and fermented. Kitchens still are, but not in the same way. In middle-class homes, there was a filter between the kitchen and the rest of the house, like those used for distilling alcohol: the cook and the household staff. Everything that happened was digested as if the house possessed two separate stomachs.

Only children were allowed to move from one sphere to another and absorb its different moods. I ate in the kitchen for years before being admitted to the dining room with which it communicated through a service hatch. The vast room had two windows, one overlooking the garden and the other the village street; two large marble tables, one of which was in the center of the room, two sideboards against the walls, a fireplace, and a stone sink. From there a door led down a steep staircase to two dimly lit rooms festooned with cobwebs that served as a cellar. Another went up to the servants’ room, where once Gilda, Rodolfo’s mother, was seized with such a fit of laughter that a rivulet of pee dripped down the stairs. She squirmed like a big supine insect, unable to turn around, the white flesh of her thighs pressed into thick black stockings. Another maid, who didn’t last long and ended up becoming a cloistered nun, dismayed everyone by her habit of drying damp dishcloths in the oven and ironing with one hand while reading the story of some mystic with the other.

The kitchen of my memory

The kitchen of my memories is not always a serene and hospitable place. The threat of the ‘guards’, whom Rodolfo invoked to bring me to my senses, was, for a child of four or five, akin to the arrival of big men, hooded and wrapped in black cloaks, like the sinister figures who arrested poor Pinocchio. Or the end-of-year eel twisted on itself in a box that I took for a frightening black snake. I vividly recall that kitchen disfigured by the excitement on the morning the radio announced the invasion by Soviet tanks of Prague. Augusta, who had absorbed the general nervousness, let the milk overflow, spill, and drip from the stovetop. Against her phlegmatic nature, she exploded into a sequence of expletives barely softened by the presence of us children. But on certain evenings, when – to put my courage to the test – I offered to go into the garden, plunged in semi-darkness, to pick wild arugula for the dinner salad, the yellow rectangle of the window, lit by the old hanging lamp, guided and reassured me.