By Francesco Bianchini

When I was five years old, I was taken to see the queen of Belgium parading through the streets of Rome. There was great anticipation for the state visit by Baudouin and Fabiola, married a few years back in a so-called fairytale wedding. That did mean something to me, as I knew my own country hadn’t had a queen for some time, and this would be a unique and rare opportunity to see royalty in the flesh – ermine mantles, glittering crowns, a queen garbed in a long gown studded with gems.

Queens had populated many of the tales that my great-aunt read to me, and they usually lived up to the image: beautiful, elegant and – it goes without saying – brimming with benevolence. They spent their existence sitting on carved and gilded wooden thrones, traveling in golden carriages, inspiring their subjects with such regal sights. (Except, of course, in the stories when they were wicked and witch-like, poisoning little girls and boys, and tormenting their subjects. In those cases there was invariably something tragic looming over their fate, but usually – by the end – everything worked out beautifully.)

What I expected…

What I expected…

The royal route was announced, and it turned out that the Belgian monarchs would pass through the street where my father’s cousin lived. The family could comfortably watch from a window. Other people had meanwhile thronged below, bedecked with flowers and flags, with children placed in the front row. As the cavalcade approached, I – leaning over the window sill, squashed in front by my excited family – could hear cheers roaring nearby. A dark limousine turned our corner at slow speed flanked by policemen on motorcycles. Everyone craned their necks and stretched on the tips of their toes to catch a glimpse of the royal pair in the back seat of the open-air car.

What I got…

I looked keenly but could see no queen. Where was she, I asked. ‘Why, she’s right there in the car, and she’s looking this way. Do wave!’ Well, they expected me to believe that the drab lady sitting next to a guy that because of his military cap seemed like a policeman, was a queen! A woman with the same sort of hat that my grandma – who was certainly no queen! – swathed over her head just to go on errands. Even Fabiola’s dress, a plain navy-blue suit, had nothing regal about it, and she was adorned solely with a small brooch, a trifling thing, pinned to her shoulder. What was the point? What reverence could she expect if she didn’t even bother to present herself as befits a queen? I slipped from under the adults’ legs, determined to boycott the rest of the show; plopped myself in an armchair, and sulked for the rest of the morning.

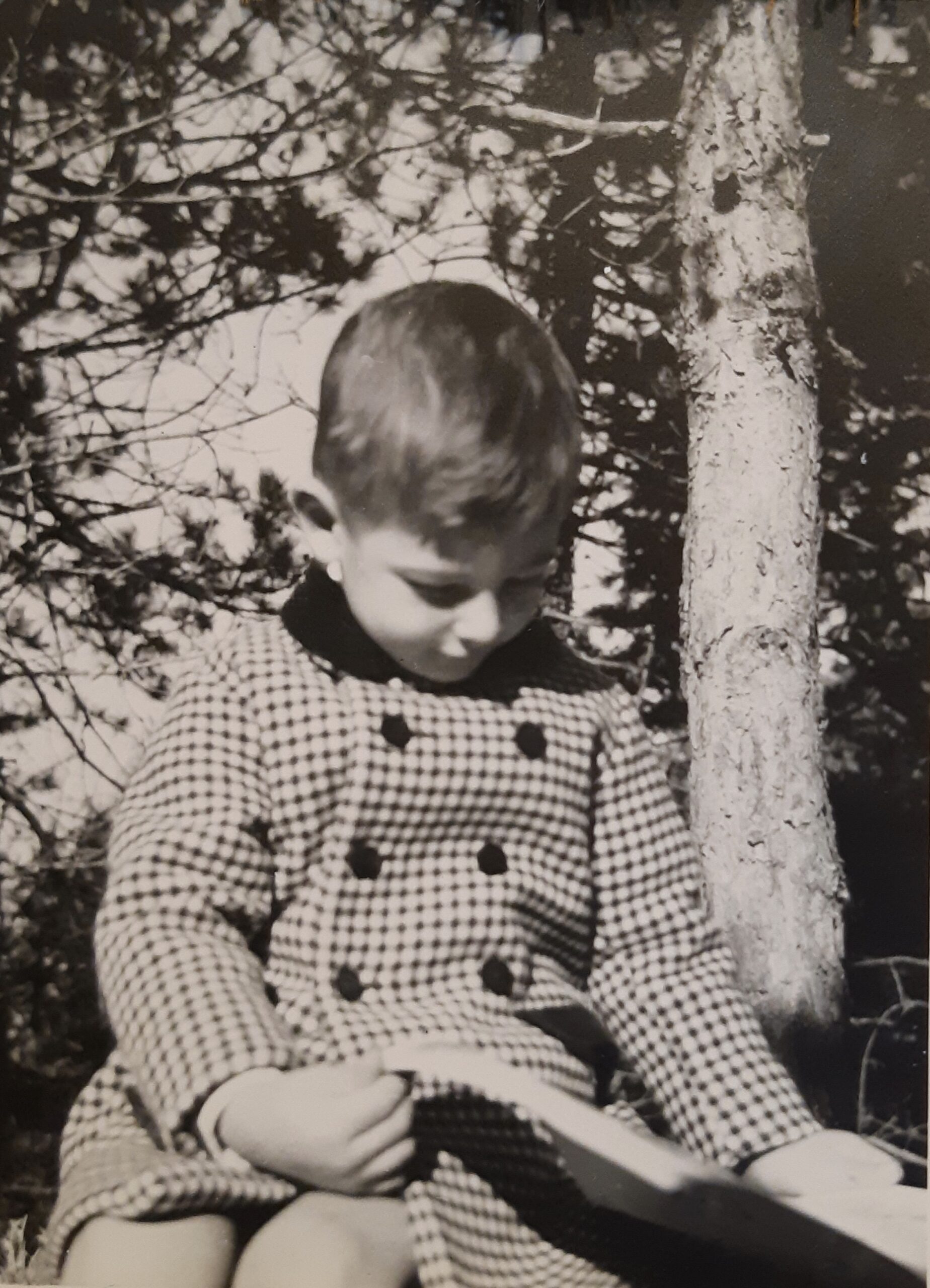

The disgruntled royal watcher

And that’s when the scent of lunch began filtering down the long hallway from the kitchen door; an enveloping aroma that, without overpowering, embraced furniture and draperies; crept across the herringbone parquet floors, contrasted with the smell of a cigarette someone was smoking in the warm March air. There was a hint of fresh spring onion, tamed by the creamiest butter; a faint honeyed hint of toasting, as after haymaking; a suspicion of excellent broth, a rich distillate of the finest meats, and even a remnant of the incense that lurks in the aisles of certain Baroque churches. There was no prevarication of one thing over the other, rather a unison – like a cappella singing. That is my adult sensitivity speaking out, and not the impressionable nose of a little child who has, however, retained the trace of it for decades.

The parade route, Via Condotti, Rome, as seen from the Spanish Steps

When the time came to sit at the table, we discovered nestled in the whiteness of monogrammed porcelain bowls, mounds of steaming golden stars – what am I saying? – bushels of gold coins, each distinct enough to be counted; each shining beneath the fumes, as if lacquered by a mantle of a most august orange-yellow hue. Our hosts, Milanese by birth, had their cook, Lina, with them. There could be no doubt whatsoever that the recipe had been executed with great respect and ‘without deceiving the gods’ as Carlo Emilio Gadda himself – doyen of all writers of Lombardy – had said of risotto alla milanese: broth and marrow of beef from the Po Valley, butter from Lodi, Soresina or at least Casalpusterlengo – in short from the lowland springs of the valley; and of course saffron strands from Carlo Erba. ‘Just a little more than al dente on the plate: the grain soaked and puffed with the aforementioned juices, but individual grain, not sticking to its fellows, not soaked in a slime, in a wetness that would turn to muck. Grated parmesan cheese is barely admitted by connoisseurs; yet it is a trivialization of Milanese sobriety and elegance.’

Taste buds, nose and eyes, retain the memory of this truly royal dish, as vivid as its color, but whose traces were lost from a certain moment on. Now we get rice grains drowned in butter, all lumpy and dyed an anaemic canary yellow, rather than the sumptuousness of that first incomparable tasting. Like a queen without her tiara and gemstones. Returning from Rome to our own Umbrian village, I complained to my great-aunt. Her stories of royal ladies were far preferable to the queens of the real world; those with no sense of shame in presenting themselves to the public in clothes bummed from her lady-in-waiting!