By Francesco Bianchini

Scarce are the memories of my father in the kitchen. Childhood ones I mean, because it was only after he separated from my mother, late in life, that he discovered a predilection for a place that had no more intrigued him as a young man than the room where ironing was done, or the pantry where food was stocked. And Papa never seemed to fuss over food; he did not like dessert, unlike Mama, who could not complete a meal without something sweet. And she would buy family-sized packages of commercial jams, which my father looked at with disdain, deploring the waste of fruit from our farmland that she ‘let rot’. These harmless intersecting idiosyncrasies did not contribute to their ultimate antagonism and rift. As an adult I realized that my parent’s marriage failed because they concentrated on each other’s faults and/or perceived bad motives instead of pooling their good qualities; an axiom I have witnessed in numerous couples.

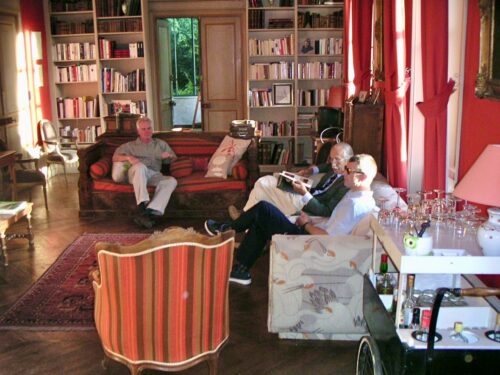

Travelling with papa (sitting between Dan and me)

Papa did not know how to be alone. Or rather he was unable to rejoice in solitude. He needed his court. It was surprising for me, therefore, to find my father ‘solo’ in the kitchen from time to time. There he perfected risotto, his specialty; yet in the preparation of it he expected us each to serve as scullions, and help clean up all the utensils he had managed to soil – virtually everything in the place. With the onset of winter, he’d prepare homemade candy. ‘Barley sugar’ he called the confection – although I know not why, as there was no barley in the stuff. Always enchanted by the transformation of commonplace things into objects of beauty, however, I’d watch with apprehension as the pots with water and sugar simmered. If the mixture thickened abruptly and burned, the whole mess was thrown out, and it was necessary to start over. But Papa knew exactly when to take the mixture off the heat, foaming and viscous to the right degree. Then he’d slowly pour the goo over the marble countertop, greased with olive oil; an alchemy comparable to incandescent magma that in transition from crucible to mold, solidified into a ring of gold. On contact with the cold surface, the liquid congealed quickly, but before it had fully hardened he’d cut it into little squares, glistening like the stained glass windows of a cathedral; fragments seemingly of amber that had imprisoned a flash of the dying sun, a bubble of life, of air, of water, even an insect, a million years old. Once he’d distributed to us the broken and splintered fragments, he stored the rest in a tin box that he kept in his nightstand drawer.

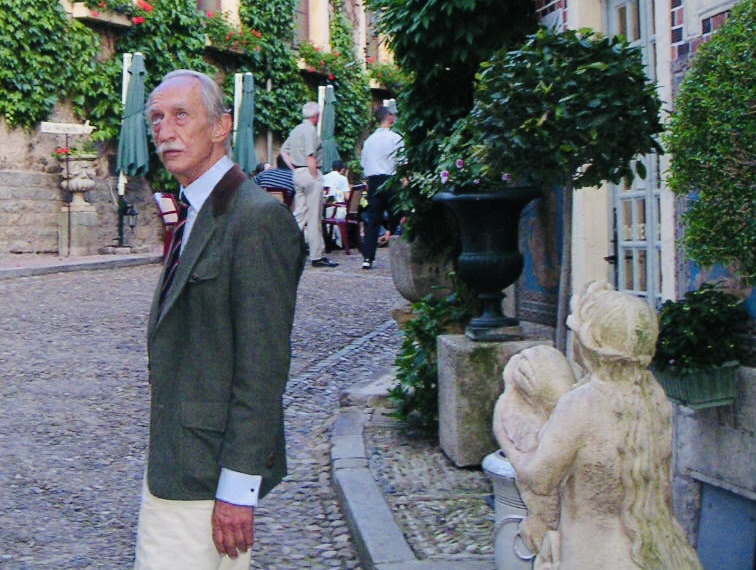

Papa looking fretful and bored

Some months before his death, my father joined Dan and me in Burgundy where we were visiting yet more properties we dreamed of buying. His health was declining and certain tantrums uncharacteristic of him were becoming more frequent. He’d always been in absolute control, firmly holding the scepter of command, but now he was reduced to being carted around. From his exile in the back seat he retaliated by loudly challenging the instructions of the GPS. His pointy knees dug into the back of my seat, and his repeated sighs and lamentations sickened the atmosphere. Luckily for us, his cell phone rang continuously and when he answered, as if by magic, he’d cease the snorts and groans while histrionically rattling off all the harassments to which we were subjecting him.

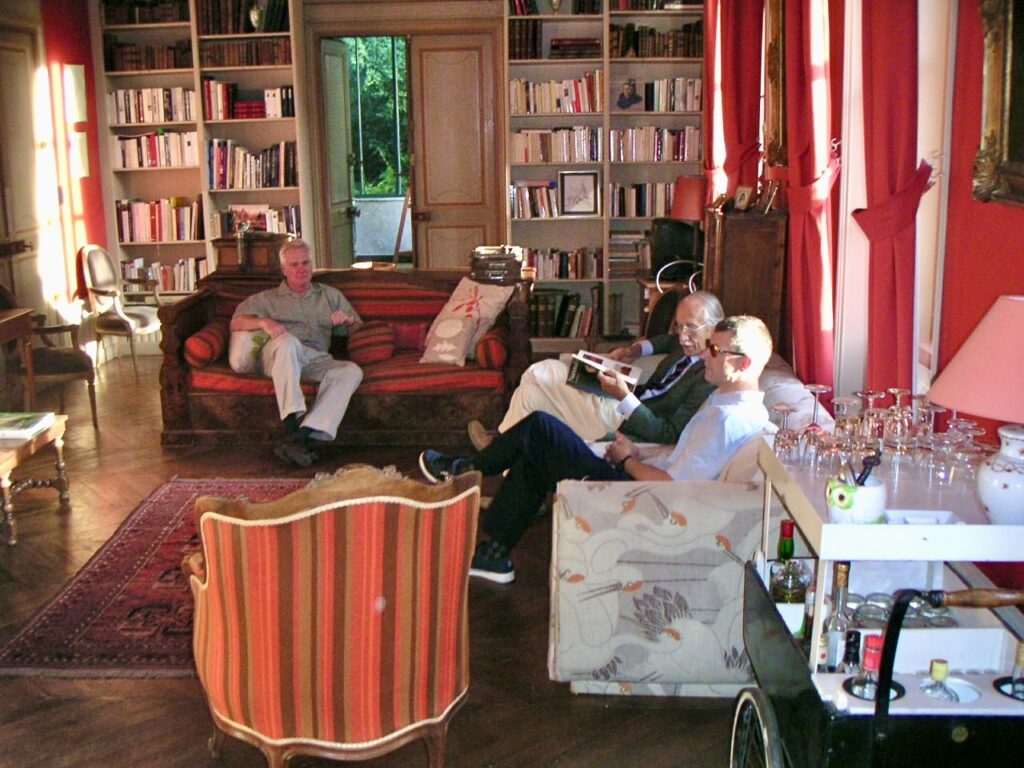

The salon, where papa exiled himself to gobble gummy candies

As a treat, we planned a stay at a hilltop chateau we’d discovered some years before in Haute-Savoie. There guests were housed in elegant suites and could enjoy a wooded park with splendid views of the Val Maurienne. The owner, whom we’d befriended, also offered a refined table d’hôte planned around the produce from his garden. We arrived early in the afternoon to take advantage of the beauty and amenities of the place, but Papa – realizing it would be several hours before he could eat – was panicked. What was he going to do in all that time? Weren’t there nearby attractions we could visit? Try to relax, I advised, and just do nothing at all for a change.

Château des Allues, Savoie

I left him sitting, dispirited, in the living room after he’d deplored the dinner menu and moaned about the guests he’d be forced to share it with. Dan relieved his accumulated tensions by soaking in a massive cast-iron tub, and I found refuge in a lounge chair under a 100-year-old sycamore tree facing the view. In the serenity of the late spring afternoon, scented by the flowering slopes, I imagined that my father, despite all his frailties and tantrums, would most likely torment us for a few more centuries, but I did hope that the enchanted setting of the place would appease him. He could have taken a stroll in the garden, perhaps gotten interested in the paintings and fine furniture in the reception rooms, or even stretched out on the bed in his room. But when the bell rang to announce the cocktail hour, giving our host Stéphane a chance to serve his coterie the homemade liqueurs and aperitifs, I found my father exactly where I had left him, bored and still discontent. Greeted nicely by the other guests, he just stared sourly. It was then I realized he actually could not speak because his mouth was full of gummy candies; so very full after two hours of stuffing his mouth with the contents of an entire bowl, where nothing remained but a pile of crumpled papers.

The view from the sycamore tree

My father died just a year later, the result of a stroke that caught him off-guard and alone in his bachelor apartment. The family, whom he had mostly kept uninformed about the affairs and affections of his later years, only learned of his illness when he was rushed to the regional hospital. I often think – perhaps too late – of the commonalities I later discovered I had with him: those good things that, when shared, might have built the foundation of a truly satisfying relationship. There were also those annoying traits he had cultivated when he was well on in years; traits that now make me smile, and that I also – strange to say – miss.