Mister Kelly’s, London House & All That Jazz

By Megan McKinney

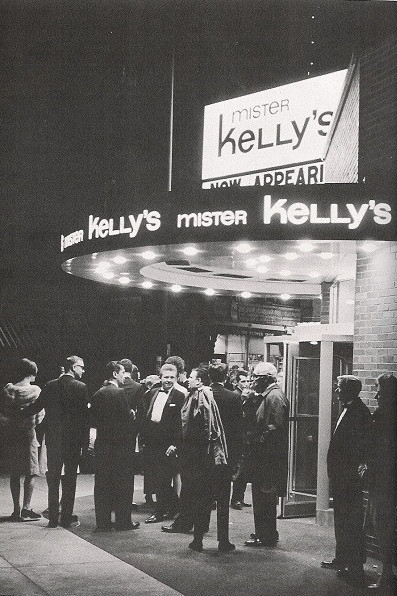

It was a moment of positive energy on Rush Street. And—look—everybody dressed for the evening!

We hear so much of Chicago’s great cultural traditions and amenities but so little about the city’s towering history of jazz clubs. Yet, mid-century Chicago was world-famous for these clubs—particularly Mister Kelly’s and London House. In the 1950s, these two names, plus The Blue Note, were acknowledged even by the most New York-centric Manhattanites as—possibly—superior to anything their own city had to offer.

New York’s 52nd Street had been sliding downward, after a 15-year reign at the top of the international jazz world, and Chicago’s clubs were ascending. But, today, amazingly few people even know who founded these now legendary showcases and—by founding them—launched one of the nation’s great eras. An era which—by the way—also made Chicago one of the most renowned late-night party towns anywhere.

This writer was assured about three years ago by one of Chicago’s most distinguished citizens—a man whose name is synonymous with our city throughout the civilized world—that Mister Kelly’s was founded by—ta-da—Ramsey Lewis!

The astonishing part of this is that no one in our little group at Gibson’s that day disagreed. We all assumed it was so.

The truth is that the great era of the Chicago jazz club was launched by a pair of South Side brothers, George and Oscar Marienthal, who in 1946 opened the Fort Dearborn Grill, an unexceptional eatery in the London Guarantee Building, at the corner of Michigan and Wacker. Within five years, they had renamed their restaurant the London House and transformed it into a fine steakhouse, where jazz was played every night of the week.

London House in 1952 at the beginning of its ascent and again in 1960, when the late Barbara Carroll was performing on a bitterly cold mid-winter night.

The London Guarantee Building, which had been a distinguished Chicago landmark by architect Alfred S. Alschuler since 1923, soon became world-famous as home of a club that hosted Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans, Dave Brubeck, Marian McPartland, Nancy Wilson, Gene Krupa and so many of the great jazz names of the period, a magic which lasted through a large part of the mid-century.

On closing night of London House, George Shearing performed his specially written tribute, A Foggy Day in London House.

In 1953, the Marienthal brothers opened a second restaurant, Mister Kelly’s, at the corner of Rush Street and Bellevue Place, where Gibson’s Steakhouse currently stands.

Today’s hugely popular Gibson’s.

Mort Sahl.

The comedians included Mort Sahl, Mike Nichols, Phyllis Diller, Bob Newhart, Dick Gregory, Dick Cavett, Joan Rivers, Lily Tomlin, Bette Midler, the Smothers Brothers and Woody Allen—we’ll get back to him later—and many of Mister Kelly’s performers received their first break at the club.

Mister Kelly’s wasn’t Barbra’s first gig, but it was close. However, her career catapulted almost immediately. (Thank you, George and Oscar.) About the time New Yorkers were paying scalper prices for must-have tickets to Funny Girl on Broadway, the above picture surfaced in Manhattan. Kup may have said she was “Fantastic,” but the rest of the world now agreed, easily giving her the $15,000 to buy out her contract for a return booking at the Chicago club that had given her the crucial break. She may not have returned to their stage, but she never forgot.

Sudden superstar Barbra Streisand greeting the stunned Marienthal brothers.

Standup comedian and longtime man about Rush Street Tom Dreesen was a Chicago boy.

According to comedian Tom Dreesen, who once caddied for the Marienthals, “Mister Kelly’s was the place where all the big comedians and singers from all around the world whom you might see on The Ed Sullivan Show would perform; it was the ultimate place for those who wanted a career in show business.”

Ella Fitzgerald at Mister Kelly’s.

In fact, the phrase “at Mister Kelly’s” became a recurring line on the albums of established musical stars.

Della Reese starred on one. . .

. . . and Anita O’Day . . .

. . . and Sarah Vaughan.

After all these years, the Marienthal brothers may at last receive the credit and visibility they deserve. George’s son, David, is developing a documentary on the family clubs, which also included the Happy Medium at Rush and Delaware. In preparation for the production, he has begun interviewing the great names . . . Woody Allen . . . Bob Newhart . . . and others of the now legends who played these clubs early in their careers.

Woody, sometime jazz musician and one-time standup comic, was very much a part of the period in Chicago and is still an occasional visitor to the city. During a 2014 interview with Michael Phillips for the Chicago Tribune, Woody reminisced about the London House-Mister Kelly’s era.

“(Those) were very, very good years, with all the comedians and singers in town,” recalled the filmmaker who is no stranger to nostalgia. “Downtown at the London House you had Oscar Peterson or Dave Brubeck. And Hefner attracted an enormous amount of show business people to the mansion . . . Chicago was a late-night town, and it was a very good era, but you don’t know it at the time, when you’re going through it. You never think: ‘I‘m living in an era, and someday I’ll be looking back at this.’ And missing it.”

Does this read like the premise for a new Woody Allen film?

A collector’s item: “Woody Allen, Recorded Live at Mister Kelly’s, Chicago.”

Coming up soon in Classic Chicago, Megan McKinney discusses Manhattan’s side of the story in Beyond “21” on West 52nd Street: New York’s Great Jazz Era.

Photo Credit:

David Marienthal

Author Photo:

Robert F. Carl