By Judy Carmack Bross

Simon Kerry

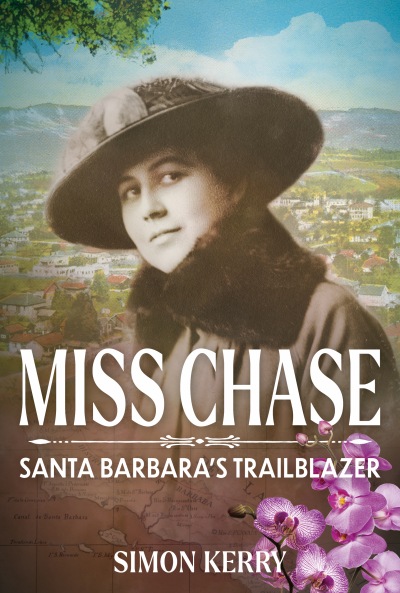

In Chicago a few years ago author Simon Kerry, the 11th Earl of Kerry, brought to life his first book about his family, Lansdowne: The Last Great Whig. He will return to Chicago in February to speak at the same elegant private club about Pearl Chase (1888-1979), his American ancestor who shaped the development of Santa Barbara and Montecito, known as the American Riviera. Kerry lives at his family’s estate Bowood in Wiltshire where he also runs a hotel, golf course and spa. Managing the estate, he adopts a similar ecological emphasis as Miss Chase did a century before.

Lord and Lady Kerry Photo: Ryan Lee Chow

Called Santa Barbara’s “Woman of the 20th Century,” the conservationist, visionary and woman’s rights activist made it her priority to develop friendships with some of the wealthiest people in America who came to that area—including Armours, McCormicks, Mortons and Harveys from Chicago–getting their help to create a city consistent in what she called the Spanish style of architecture, along with gardens and preservation regulations for one of the most beautiful areas in America. Road signs in and out through the spectacular scenery were banned thanks to Miss Chase.

“For well over a century it has been a delightful environment for tourists wanting a short break and for permanent residents looking for a sophisticated and relaxed way of living. It is the easiest city I know to navigate until it rains, and driving becomes extremely hazardous,” Kerry, who spent months researching there, said.

From the end of the 19th century, Santa Barbara was known as an artistic center with residents such as Frederic Remington working there as well as talented architects who created red-tiled roofs, central fountains, and ironworks set off against the white-washed stucco walls as well as New England-reminiscent architecture. The destruction of much of the city in the 1925 earthquake gave Miss Chase the opportunity to work with all segments of the community and develop the lasting beauty there today in the historic Spanish style.

Pearl as a young woman Meikleour House Collection

Pearl as a young woman Meikleour House Collection

Another quake, the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 when she was a student at Berkeley, helped create the leadership qualities for which she was known. In her diary at the time she wrote: “The house was rocking and shuddering as if some giant had grabbed it by its shoulders.” Despite the fact that 2,000 people had been killed all around her, the 18 year old took care of infants in a makeshift hospital as flames spread.

Tracing her roots to John Alden and Priscilla Mullins, Chase was born in Boston. The Mediterranean climate and sundrenched beaches which captivated many Americans drew her family to Santa Barbara in 1900 when it was considered to be one of the world’s most ideal health and tourist resorts. Guests arrived at the Potter Hotel which occupied six blocks of oceanfront property before it burned down in 1921. Visitors went on to buy property in Montecito where “they lavished their philanthropy on the city,” Kerry writes.

Pearl among her own papers at the Department of Special Research Collections, UCSB Department of Special Research Collections, University of California Santa Barbara Library

Among the Chicagoans who came to Santa Barbara were Sterling Morton II, President of Morton Salt, and his wife, the former Chicago debutante Preston Owsley, whom he married in 1910. Known for their generosity to the Art Institute including the Morton Wing in 1962, the family was involved with the Santa Barbara Art Museum where there is a significant Preston Morton Collection including a stunning Edward Hopper. Their daughter Susie Davidson, an art connoisseur and collector who had advised Jacqueline Kennedy on paintings at the White House, moved from the Potter Palmer II Astor Street triplex and an estate in the western suburbs near the Morton Arboretum to Santa Barbara. She remained there until her death at 84 in 1996.

Pearl Photo: Bowood Collection Trust

Pearl Photo: Bowood Collection Trust

Her daughter Ariel Hermann told us: “My grandparents called their home Dos Vistas because they had a view of both the ocean and the mountains. I think they came there in large part because of the interesting people there whom they had known in an earlier life. One of these was the very good-looking artist and esthete Wright Ludington.” Ludington was one of the founders of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

Kerry shared other Chicago connections:

“Bernhard Hoffmann who worked closely with Pearl Chase to bring about the Spanish Colonial and Mediterranean Revival style of architecture was married to Irene Botsford. She was a former Chicago debutante and daughter of the founder of the meat packing business in the city. Married in 1903, they lived in Stockbridge, Massachusetts before buying property in Santa Barbara in 1919. Her money helped fund his architectural ventures.

“Philip Armour’s daughter Lolita, who married John Mitchell, worked with Pearl Chase and was a generous donor to the city. They lived on a spectacular 70-acre estate known as El Mirador in Montecito.

“Cornelius K.G. Billings, raised in Chicago before becoming an industrialist and a tycoon whose many ventures included being co-founder and Chairman of Union Carbide, was a generous philanthropist to the city. Among the magnificent homes he built across the United States was Asombrosa—Spanish for amazing–in the hills of Montecito.

We asked Kerry to tell us more about Miss Chase.

“For as long as I can remember I have been fascinated by my American ancestors. When I started to learn about my great-grandaunt I was treated to numerous anecdotes about powerful individuals, invariably men, who confessed to a feeling of dread when they were told that Miss Chase had called. It habitually meant that a cherished plan they were hatching was about to be exposed to public scrutiny. I wrote this book to satisfy my curiosity. How, I wondered, could a single woman, who did not appear to have had the benefit of any great institution behind her, evoke such feelings? What motivated her, enabled her to overcome the odds and be successful? The answer I discovered was her vision. A vision of beauty and possibility.

“In one sense, her vision was simple. For people to be happy, they had to live in an uplifting environment and so, they must feel ownership of their communities. Communicate, Cooperate, and Coordinate were her three watchwords and where possible, she worked with power rather than against it. Her clear thinking and persuasiveness made even the most hard-headed men come round to her point of view.

“For over 70 years her vision endured, and she established herself as Santa Barbara’s woman of the 20th century. From championing the rights of Native Americans, to town planning, the wilderness conservation, the preservation of California’s Spanish heritage and the spirit of volunteerism, there were few areas of her community’s life that Pearl didn’t have a hand in shaping

View of the terraces and house at Bowood in Wiltshire Photo: Anna Stowe

Bowood House east front and border Photo: Anna Stowe

Bowood House east front and border Photo: Anna Stowe

What would Miss Chase feel about what your family is doing at Bowood?

“During the 1970’s when my father was taking on responsibility for Bowood, he and Pearl frequently corresponded and discussed environmental problems and civic affairs in their respective communities. Ensuring that Bowood is both productive and carefully managed continues today.”

Bowood House and Grounds in frost Photo: Anna Stowe

Bowood Hotel, Spa and Golf Resort Photo: Arabella Unwin

Autumn trees Bowood arboretum Anna Stowe

Autumn trees Bowood arboretum Anna Stowe

Why do you enjoy writing about leadership?

“I am fascinated by history and people. Outcomes are dependent on individuals. How individuals lead varies. As a biographer I get to delve into the life of another person and discover what characteristics guide them. I think it is helpful to put leaders in the spotlight. Also as a biographer the primary archival sources are central to the work and I avoid family piety. That said, I respect the values that both the Fifth Marquess of Lansdowne and Pearl Chase lived by and I do believe that today these are never more important.

“She is the model of a great leader – rather than focus on her own achievements, she humbled herself in serving others while tenaciously standing up to prejudice and injustice and dealing with difficulties head on. This unusually gifted woman with razor-sharp intelligence respected others, whoever they were, whatever their background and faith, listening and caring for them, and discerning their needs. She had special respect for women, inspiring, mobilizing, and spurring them to harness their gifts and talents for the good of others. She saw potential in everyone.

“She was modest yet could stand up for herself and for causes that energized her. She had boundless energy but knew when to say no. She had a pioneering spirit and a clear perspective so prescient and relevant today.

Pearl as a young child Photo: Meikleour House Collection

“Her legacy remains strong and her memory is kept alive through the many organizations that she influenced. The open spaces and fine buildings that make Santa Barbara a unique American city and enable residents to have a better quality of life are due to her work. The campaigns she organized through her environmental advocacy quickened the modern environmental movement by raising public awareness of environmental issues. Today, California is implementing some of the best environmental education in the country. Where she pioneered, new organizations are now connecting education, environment, and community, inspiring them with a modern vision.

“Her contribution to the state park system and historic preservation is seen in the success of La Purísima Mission State Historic Park at Lompoc and El Presidio de Santa Barbara State Historic Park. By adding her voice and finances to the campaign to support Native Americans, she helped change the way grassroots organizations addressed national, state, and regional issues. The Association on American Indian Affairs continues to advocate on issues that support sovereignty and culture.”