By Elizabeth Dunlop Richter

American Landscape by Joyce Owens

American Landscape by Joyce Owens

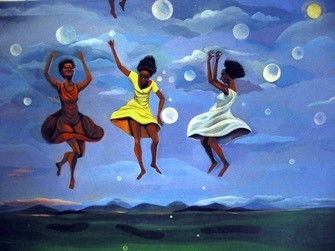

“I love the irony in American Landscape”– you may see ‘Florence” (my name for her) as dancing, or rising above the romanticized field. OR responding to an unseen threat in an idealized setting. She is not smiling. But there’s no question that her people created that field, made it productive.” This thoughtful analysis by Sharon Feather, a Lake Forest collector of Joyce Owens’ artwork, underscores the power of Owens’ paintings.

Owens shared her own analysis in her blog: “American Landscape shows a little girl who, in this country, is sadly still marginalized and not considered equal in a field that represents the country built, in part, on the backs of her ancestors. The birds, bright sky and flowers represent hope that things will change.” Sometimes mysterious, sometimes historical, rich in saturated colors, always reflecting the Black experience and particularly the experience of Black women, Owens’ paintings and sculpture have engaged viewers for four decades.

Joyce Owens photo by Robert Kameczura

Now a resident of Lincoln Park, Owens has arguably been a recognized artist since she was five years old. Growing up in Philadelphia, PA, she loved to draw dancing figures. Her mother showed some of the drawings to friends who told her, “If your daughter is five and did these drawings, you need to put her in an art program,” Owens recalls. Her parents did not follow up immediately but encouraged her, and Owens never gave up her love of making art, from arts and crafts programs at the local playground to focusing on art in high school. She learned early, however, that she had to fight for her rightful place.

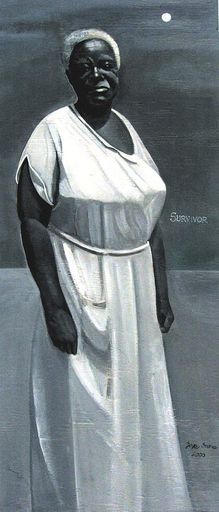

Survivor Spirit Betty by Joyce Owens

In high school, she was delighted to see the announcement posted on the bulletin board that she was named art editor of the yearbook. When the teacher in charge saw her for the first time, however, he told her that she had to submit more samples of her work. She submitted more samples, but was then was told that another student was named to the position. With her parents, she confronted the principal, who offered lame excuses. Owens knew as the Black girl, she was losing out to white competition. She offered a compromise: to be co-editor. “The fact that they accepted this said the school knew it had done the wrong thing,” Owens noted. “This led me to Howard University. I needed to go someplace where people weren’t trying to do me in.”

Yale MFA Graduate photo by Jim Alexander

Owens continued her art studies at Howard; her parents urged her to focus on being an art teacher to guarantee an income. Her stepfather was a teacher. Her mother, an acclaimed opera singer who sang with opera companies across the country, also worked as a water collections supervisor for Philadelphia to ensure she could pay the bills. “She told me you’ve got to make a living,” remembers Owens. Further advice came from Howard art professor Leo Robinson, who urged her to switch her major from art education to painting, get an MFA and then teach at the college level. Keeping her career options open, she applied and was accepted at Yale for her MFA, the only African American in her class. Completing the two-year program, she was faced with a challenging job market, hoping for something other than teaching. A classmate, she recalled, had applied and was turned down for over 100 jobs.

The Medieval in America by Joyce Owens

Chance took her into the television industry. A friend worked for the CBS station in Philadelphia. Owens applied and was hired as a producer. Following a boyfriend to Chicago, she then found work at WBBM TV as Graphics Coordinator, a position created just for her. She worked closely with iconic anchors Bill Kurtis and Walter Jacobson. “It was a nice job in that I met all kinds of people like Mohammed Ali and James Earl Jones,” she recalled. She would also marry and divorce while at WBBM. Thanks to reporter Renee Ferguson, she met Monroe Anderson, a Chicago Tribune reporter who would become press secretary to Mayor Eugene Sawyer. “Renee kept telling each of us that we were interested in the other,” Joyce remembered with amusement. The chemistry worked and they remain happily married today. Owens left WBBM to work on her art.

(Left to right) Mayor Eugene Sawyer and Monroe Anderson

Wonder Woman by Joyce Owens

She pursued painting full time for several years as her family grew to include two sons, Scott and Kyle. A part time teaching opportunity proved unexpectedly appealing. Owens was invited by Bob Weitz, Chair of the Art Department at Chicago State University to teach part time and to mount a solo exhibition of her own work. She was able to create a work-life balance while her children were young. She decided to teach an Introduction to Art course with an experiential approach. “It’s crazy to teach types of media only from textbooks. I took my students to labs and studios at the university to see real artists at work. We also visited museums and exhibitions of different Chicago artists.”

Survivor Spirit: Seated Woman by Joyce Owens

She would eventually accept a full time tenure track faculty position at CSU and when Weitz retired in 2006, she was promoted to Curator of the Galleries Program. She remained at CSU until 2015; “I really enjoyed it, but I needed to spend time on my own work.”

Woman Rise by Joyce Owens

“I made the decision to do work that was positive; my themes are race and gender. I decided not to do angry black men and angry black women. I painted what I saw. I want people to see positive examples and I saw many.”

In Owens’ own family, one uncle was a jazz pianist, the other, Jack T. Franklin, a noted photographer, and one grandfather was a school principal in the South. “I knew educated, entrepreneurial Black people growing up. I once asked my sister why my grandfather worked for the post office. She said he was the first African American to work for the Philadelphia post office in the 1920’s, and her grandparents were listed in a book on Black elites Philadelphia in the 1920’s.” Her subjects whether historic or contemporary, are strong and often seemingly pushing back against racism with purpose and optimism.

Woman in Shirtdress by Joyce Owens

Woman in Shirtdress by Joyce Owens

Owens’ lyrical and evocative work is collected nationally and internationally and has been exhibited in numerous museums, galleries and juried shows. Her paintings have been shown by NATO in Brussels and at US embassies in Monrovia, Liberia; Georgetown, Guyana; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia at the African Union and Stockholm, Sweden through the Art in Embassies program of the US Department of State. Included in such publications as Daniel T. Parker’s book “African Art: The Diaspora and Beyond” and “A Proud Continuum: Eight Decades of Art at Howard University,” Owens was awarded first prize for her Survivor Spirits installation at the ninth Annual Art Open at Women Made Gallery in Chicago. She consults and curates independently for individual artists and for the Sapphire and Crystals collective. She is associate editor of the Journal of African American History.

From the series “Revealed: Truths and Myths” by Joyce Owens

In her blog, Owens talks about her series of figures in Renaissance dress called “Revealed: Truths and Myths.” “I was inspired to create work asking, “Who is beautiful,” thinking about what I was taught about paintings portraying women from the Renaissance period who were considered beautiful. I realized many of them had the good fortune to be married to or be the daughters of wealthy merchants. They were painted in their finery including jewels, fancy hair and clothing. So I painted after the portraits, imposing a mask alluding to an African ancestry, wondering if women of African descent were portrayed in art that was routinely found in books and museums would the aesthetic be different? Would black have been considered the standard of beauty?”

Owens has not limited her creativity to painting in oils and acrylics. She also explores 3-D art forms. When she decided to try sculpture, she talked to Richard Hunt, the revered Chicago-based sculptor with an international following. His advice was succinct: “Just do it.” Following his advice, she creates multi-media masks and sculptures that evoke the energy, spirit, and imagination of her paintings.

|

|

Najee Dorsey, an artist and entrepreneur who operates an online gallery and represents artists across the county, has known Owens for ten years and has promoted her work for nearly eight. “She is a trained artist at the highest level and has a signature style. I love her various series in a variety of media.” Founder and publisher of Black Art in America magazine and through his own Garden Art for the Soul, he promotes and sells African American themed objects that help grow the audience for African American art. He applauds her branching into new marketing ventures, offering prints and products featuring her work. He observed that the market for African American art is very strong now, to some degree because of the focus on Black empowerment and justice. “Not everyone is in a position to afford original art. People will grow their interest in an artist through prints and other uses of an image,” he explained, “and it also provides revenue for the artist.”

Owens is a perfect example of his advice. She has permitted selected works to be reproduced on posters, prints, tote bags, and stationery. Thanks to the pandemic, there is one more way you can experience Owens’ evocative art. You can wear it on a COVID-19 mask!

In the midst of our national conversation about race, Owens offered her mother’s opinion. “The only thing she regretted was that she was so light skinned, people thought she was white. She married two darker-skinned men so her children would be darker,” Owens told me. As an artist and teacher Owens continually celebrates American history and offers a unique perspective on the Black experience from her own point of view.